Kennedy

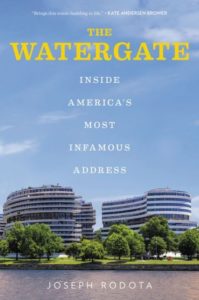

The Watergate: Inside America’s Most Infamous Address

by Kitty Kelley

Hotels can intrigue, even captivate. In the pantheon of places, nothing tantalizes so much as a good story situated in a hotel, particularly a luxury hotel with hot- and cold-running bellhops, genuflecting valets, and chandeliers that drip with crystal. (Think the Metropol in A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles.)

Hotels can intrigue, even captivate. In the pantheon of places, nothing tantalizes so much as a good story situated in a hotel, particularly a luxury hotel with hot- and cold-running bellhops, genuflecting valets, and chandeliers that drip with crystal. (Think the Metropol in A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles.)

Built on superstition, few hotels have a 13th floor — most elevators go from 12 to 14 — but each floor can hold secrets, whether dreadful or delightful. As such, hotels have been the subject of movies (“Grand Hotel” with Greta Garbo; “The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel” with Judi Dench); novels (Hotel Du Lac by Anita Brookner); children’s books (Eloise at the Plaza by Kay Thompson); a rollicking BBC television series (“The Duchess of Duke Street,” the story of the king’s mistress, who owned the Cavendish Hotel in London); and even an Elvis Presley classic (“Heartbreak Hotel”).

Hotel sites beguile, possibly because they provide escapes from the real world and adventures for the escapees, which translates into vicarious pleasure for the rest of us.

Whether fact or fiction, the standard recipe for a good hotel story contains basic ingredients:

1 lb. Scandal

1 c. Sex

2 c. Eccentric guests

1 dash Crime

1 pinch Skullduggery

For added spice, mix in two cups of chopped celebrity and bake for 350 pages. Voila. You’ve got the perfect hotel-story soufflé.

Joseph Rodota followed this recipe to write his first book, The Watergate: Inside America’s Most Infamous Address. For scandal, crime, and skullduggery, he provides the 1972 burglary of the Democratic National Committee, which led to the resignation of President Richard Nixon, which, in turn, spawned a great film, “All the President’s Men.”

For eccentricity, Rodota showcases Martha Mitchell, wife of Nixon’s attorney general, and her midnight phone calls. Freshly sprung from a psychiatric ward in New York to move to Washington with her husband after Nixon’s inauguration, Martha soon gave hilarious definition to drinking and dialing. Belting back bourbon late at night, she frequently called Helen Thomas, UPI’s White House correspondent, to unload on “Mr. President.”

For eccentric good measure and a smidge of sex, Rodota also tosses in the Chinese hostess (cue Anna Chennault) who served “concubine chicken” at her Watergate dinner parties.

From John F. Kennedy to John Mitchell to the johns who paid for prostitutes, this book drops more names than a prison roll call. With the exception of Monica Lewinsky, who lived in her mother’s Watergate apartment in the 1990s, where she hung the blue dress that led to the impeachment of President Bill Clinton, most of the dropped names are Nixon-era Republicans (Senators Elizabeth and Bob Dole), Rosemary Woods, and cabinet members like Maurice Stans, John Volpe, and Emil “Bus” Mosbacher.

With skillful research from old newspapers and magazines, oral histories from presidential libraries, and a few interviews, Rodota has fashioned an interesting story about the white concrete edifice that looks like a giant clamshell. With three buildings of wrap-around co-op apartments terraced with egg-carton balustrades, the Watergate, facing the Potomac River, sits adjacent to the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.

To tell his story from the beginning, Rodota burrows into the complicated bureaucracy that surrounds any major construction in the nation’s capital. He whacks through the weeds of proposals and counter-proposals from the financiers, architects, and developers to the National Capital Planning Commission, the DC Zoning Commission, the National Park Service, the Commission on Fine Arts, the committee overseeing the National Cultural Center (later to be named the Kennedy Center), the U.S. Congress, and, finally, the White House. All had to reach agreement before a shovel broke ground.

Beginning in 1962, numerous hearings were held to discuss plans for Watergate Towne, a complex that would include a gourmet restaurant, spa, beauty salon, grocery store, liquor store, cleaners, florist, bakery, and a boutique of designer clothes for women. Still, there was concern, especially over the project’s financing and what the Kennedy White House called “the Catholic problem.”

As the first Catholic to be elected president — and only by 100,000 votes — John F. Kennedy knew his religion was problematic to many. As president, he genuinely wanted to make Washington “a more beautiful and functional city,” which the Watergate project promised to do. But he would not sign off on the $50 million proposal because it was largely underwritten by the Vatican, then the principal shareholder in the developing company Società Generale Immobiliare.

The formidable columnist Drew Pearson stoked controversy over “popism” with a syndicated column headlined: “Vatican Seeks Imposing Edifice on Potomac.” A group called Protestants and Other Americans United for Separation of Church and State mobilized its members.

Within weeks, the White House received more than 3,000 letters opposing construction of the Watergate and, according to one, “having Miami Beach come to Washington.” Most voiced outrage that Kennedy would be under clerical pressure to do the bidding of “the world’s richest church.” The Vatican soon divested its interest in the project, and, by November 22, 1963, most objections were muted.

Probably because there is no breaking news in Rodota’s book, his publisher sent a letter to editors and producers trying to burnish the fact that “The Vatican, the coal miners of Britain, and Ronald Reagan have something in common: They each owned a piece of the Watergate. Ronald Reagan held a financial stake in the Watergate complex shortly before becoming president, a fact that has never been made public before this book.”

Wowza! Stop the presses!

Yet the author does a good job of mixing historical facts with personal anecdotes to tell the story of what was both the most famous and most infamous hotel in Washington, DC, until the presidential election of 2016. Perhaps Rodota will follow this book with another hotel story entitled Tales from the Trump International, which might indeed provide some needed wowza.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

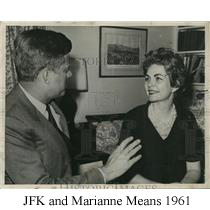

Remembering Marianne Means

by Kitty Kelley

I’d much rather be hoisting a glass with Marianne Means, and hearing her rant about “that vulgarian” in the White House than writing this valedictory, but she went to the angels a few days ago, and her death leaves me with an empty glass, albeit a full heart.

You may have noticed The Washington Post gave her a large obituary, and applauded her as a “trailblazing White House correspondent,” which led to 50 successful years as a syndicated columnist for Hearst newspapers. The obit mentioned that Marianne made a crucial connection as a college student with then-Sen. John F. Kennedy, when he was campaigning for President in Nebraska. In the White House he sought to help her make her way amidst a predominantly male press corps.

You may have noticed The Washington Post gave her a large obituary, and applauded her as a “trailblazing White House correspondent,” which led to 50 successful years as a syndicated columnist for Hearst newspapers. The obit mentioned that Marianne made a crucial connection as a college student with then-Sen. John F. Kennedy, when he was campaigning for President in Nebraska. In the White House he sought to help her make her way amidst a predominantly male press corps.

“Give her some stories,” the President told one aide. “Give her all the help you can.”

For anyone who knew Marianne then as a pretty blue-eyed blonde—“farm fresh,” recalled one photographer—and JFK as an inveterate chaser, certain assumptions were made, and those assumptions were to Marianne’s advantage, although her romance then was not with Kennedy, but with his deputy press secretary.

I met her many years later in Georgetown, where she lived all of her life since moving from her parents’ farm. She graduated from the University of Nebraska with a Phi Beta Kappa key, and later earned a law degree from George Washington University. We lived near each other, shared the same hairdresser and many mutual friends. Marianne was great fun, wonderfully opinionated, and breezily direct about everything—except for her husbands and lovers. By the end of her life she’d collected five of the former and lots of the latter, but she did not kiss and tell. She would’ve been appalled by #MeToo.

Before Pamela Harriman arrived in Washington, Marianne Means was entertaining presidents, vice presidents, senators and congressmen. “Not all at once, mind you. I saved Lyndon Johnson for a special group of people,” she told me in 1973 when I was writing an article about dinner parties. “As President he came to my house two times. Both times Lady Bird was out of town and both times he approved the guest list in advance.” I asked if she catered an elaborate menu for her illustrious guest. “Can you believe it? I actually cooked it myself,” she said. “The President was not a fussy eater, thank God, so I could get away with a simple dinner of roast beef, which was good because I’m just a plain old meant-and-potatoes girl.”

In the article I mentioned her cat had jumped on President Johnson’s lap. After publication Marianne corrected me: the cat had jumped on the roast beef.

When I was thinking about writing a book on Georgetown as the nexus of power and influence in Washington, D.C., Marianne was my go-to source. She knew that few places in the U.S. carried the panache of instant recognition like the 12 square blocks in the middle of the nation’s capital, which have been home to presidents and prostitutes, senators and scalawags, congressmen and convicts. Even when I decided not to write the book, we’d still meet for dinner at La Chaumiere, where she would be wheel-chaired in by one of her devoted caregivers.

One night she began talking about LBJ, and I gave her the girlfriend-to-girlfriend look. She laughed, but wouldn’t say another word. I mentioned the many references to her in President Johnson’s daily White House diaries from 1964-1967.

“Okay,” she said. She paused for a long minute. “Yes, it was an affair and, no, I won’t share it with people, not even you. It was mine and he was mine.” She was serious, almost fierce, and I realized that Lyndon Baines Johnson had been enormous in her life. Later that was confirmed when I read John Seigenthaler’s oral history in the John F. Kennedy Library regarding the 1964 Democratic National Convention when Robert Kennedy was given a monumental ovation The rancor between then-President Johnson and former Attorney General Kennedy was visceral. Seigenthaler, administrative assistant to Kennedy in the Justice Department, was a close personal friend. Flying back to Washington on the press plane after the convention, he recalled: “I remember Marianne Means who loved Lyndon and really worked on Bob. She was always a friend of mine. [But] I was cold to her on the flight that night.”

During out last dinner Marianne said to me: “I think it’s terrible Johnson has not gotten his due as a great president and he was a great president. Look at all he did for civil rights.”

I agreed, then whispered, “Vietnam.”

“Pew,” she said. (Yes, “pew” was her exact quote.) “Vietnam was started by another president…. Johnson made sure both his sons-in-law [Patrick Nugent and Charles Robb] served—in safe positions, of course, but both went to Vietnam…. Ben Barnes [former Lt. Gov. of Texas] is now the leading guy for helping us try to restore Johnson’s place in history.”

She talked about inviting President Johnson to one of her weddings. “I think it was my second or third…. It was in my small house on 32nd Street. Johnson came. My relatives still remember how they had left something in the car and had to run outside to get it but couldn’t get back in because of the Secret Service.”

“Must be nice to have a lover who is protected at all times,” I said.

“Nice try, Kitty Poo, but I still won’t tell you.”

We both laughed at my clumsy effort to get more information, and now she, God bless her, gets the last laugh.

Photo: Kitty Kelley (seated); Standing, left to right: Barbara Dixon, Susan Tolchin, Marianne Means and Sandra MacElwaine.

Crossposted with The Georgetowner

The Nine of Us: Growing Up Kennedy by Jean Kennedy Smith

by Kitty Kelley

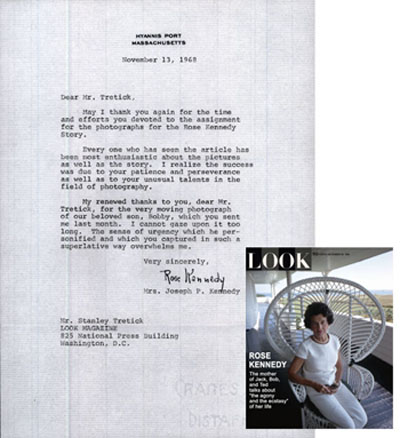

With hundreds of Kennedy books bending library shelves (I’ve written two: Jackie Oh! and Capturing Camelot: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the Kennedys), another seems like one more shamrock in Ireland — not needed for greening the landscape. But a memoir by 89-year-old Jean Kennedy Smith, the last surviving member of that storied family, might prove irresistible. Like one more chocolate in a binge. So why not?

With hundreds of Kennedy books bending library shelves (I’ve written two: Jackie Oh! and Capturing Camelot: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the Kennedys), another seems like one more shamrock in Ireland — not needed for greening the landscape. But a memoir by 89-year-old Jean Kennedy Smith, the last surviving member of that storied family, might prove irresistible. Like one more chocolate in a binge. So why not?

Caveat emptor: Don’t expect startling revelations or piercing insights. Reading The Nine of Us: Growing Up Kennedy is like sitting down with your great-grandmother to look at a scrapbook of old photographs taken with a Brownie camera loaded with Kodak film. A relic from a bygone era. Sweetly nostalgic.

You begin by already knowing the popular lore: “the nine” are Joe, Jack, Rosemary, Kathleen (aka “Kick”), Eunice, Pat, Jean, Bobby, and Teddy — the four sons and five daughters born to Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. and his wife, Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy, who lived to see the pinnacle of their most cherished aspirations when their second-born son, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, became the first Catholic president of the United States, and Irish Catholic at that.

This thin reverie of a book underscores the Irish Catholic heritage that produced the nine Kennedy children who grew up in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s pre-Vatican II era of Latin Masses every Sunday, meatless Fridays, grace before meals, and evening prayers.

Growing up in the 1950s, I, too, was taught by nuns to memorize, memorize, memorize — the Baltimore Catechism, not the world atlas. I can hardly locate Afghanistan on a map, but I’m still able to recite why God made me: “to know, love and serve him in this world and be happy with him in the next.” All by way of explaining why I might be more tolerant than most of Smith’s tendency to render verbatim the prayers and poems of her childhood as well as the Beatitudes from the Gospel of St. Matthew.

Smith recalls the visit Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, later Pope Pius XII, made to their home in Bronxville, where he sat on the sofa and held 4-year-old Teddy on his knee. Rose Kennedy later had a plaque made and mounted on the back of the sofa to commemorate the event. The author also relates her mother’s executive organizational skills in handling various childhood illnesses like measles, mumps, and chickenpox.

“Why spend the year cycling child after child through the flu…If one of us came down with a contagious illness, it simply made sense to her that the rest of us should come down with it too…So as soon as the doctor stepped from the room of a sibling to report an infectious disease, the rest of us were hustled inside by Mother to play…Within a week the sickness was out of the house for good.”

In previous books, Rose Kennedy has been dismissed as priggish, pious, and humorless, but her youngest daughter also shows her to be devoted to continual self-improvement for her children as well as herself. Even into her 90s, she was still trying to master a second foreign language. She lived to be 104.

At first, I assumed this slight book was ghostwritten but, as no other writer is named, perhaps not. Still, I agonized for whoever did the writing because the poor soul seemed to have no access to fresh material — no personal diaries, fulsome letters, or unpublished photographs.

Instead, the writer had to plunder the public record, cribbing a great deal from The Patriarch: The Remarkable Life and Turbulent Times of Joseph P. Kennedy by David Nasaw; Rose Kennedy’s memoir, Times to Remember; and Hostage to Fortune: The Letters of Joseph P. Kennedy, edited by Amanda Smith.

As the first journalist to reveal the pre-frontal lobotomy performed on Rosemary Kennedy, I have always been impressed by how the family used that tragedy to support their commitment to mental health. The Nine of Us does not ignore the experimental surgery, which Jean Kennedy Smith writes, “went tragically wrong…Rosemary lost most of her ability to walk and communicate,” adding that her father, who had sanctioned the procedure, “remained heartbroken over the tragic outcome…for the rest of his life.”

Yet Smith omits revealing her mother’s bitterness about what her father had done without consulting her or anyone else in the family. In her book The Fitzgeralds and the Kennedys, Doris Kearns Goodwin quotes Rose Kennedy at age 90: “He thought it would help [Rosemary]. But it made her go all the way back. It erased all those years of effort I had put into her. All along I had continued to believe that she could have lived her life as a Kennedy girl, just a little slower.”

Such a sin of omission — and there are many throughout the book — mars this memoir and keeps it from being more than superficial gloss.

Crossposted from Washington Independent Review of Books

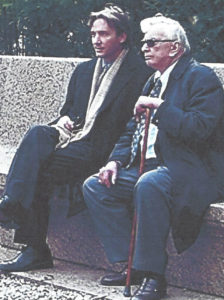

Burying Gore Vidal

See Kitty Kelley’s “Gore Vidal’s Final Feud” in the November 2015 Washingtonian magazine for an account of the consternation caused by Vidal’s final disposition of his wealth and property: “Given his penchant for dissent Vidal–who died in 2012–would be smacking his lips to know that, between his death and this fall, there has been a bitter fight over his will pitting distant relatives against one another.”

Update 11/9/15: The article has been posted at the Washingtonian website here.

Photo: Gore Vidal with Burr Steers, son of Vidal’s half-sister Nina Auchincloss Straight.

Coalition to Stop Gun Violence

Kitty Kelley spoke on December 8, 2014 at the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence 4oth Anniversary Celebration in Washington D.C.:

Kitty Kelley spoke on December 8, 2014 at the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence 4oth Anniversary Celebration in Washington D.C.:

This is an evening I’ve been looking forward to because it gives me a chance to be in a room with people I consider royalty who are enlightened and represent a sense of values that I have long admired. So I come here tonight to pay tribute to each of you for your commitment to stop gun violence.

I salute you because you have refused to be defeated by huge odds. You have not become disillusioned by the political failure in this country to legislate gun control; you have not been intimidated by the N.R.A. You have stood tall and you have not wavered. You are clear-eyed about the obstacles but you focus on your high purpose, which is to bring us back to our humanity. And in the words of that old spiritual sung by those who marched for Civil Rights–you shall not be moved.

Everything about this organization underscores humanity. You named yourself a “coalition” which by its very definition embraces outreach to others–of different religions, different regions, different races. Your roots spring from the hopeful days of the Civil Rights movement for justice and equality. To date your organization covers 47 different organizations which share your mission of non-violence. One purpose, many people.

When President Kennedy addressed the nation on Civil Rights in 1962, he said, “This is not a legal or legislative issue alone. We are confronted primarily with a moral issue. It is as old as the scriptures and as clear as the American constitution.”

But old as it might be and clear as it might seem, it sometimes looks impossible to achieve. Yet Martin Luther King, Jr., never lost hope. He told us that “the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends towards justice.” He said that arc would lead us to a place of peace for all humanity. He called the place the Beloved Community.

And tonight I feel like I am in the middle of that Beloved Community because for 40 years you have given your time, your talent and your treasure to stop gun violence. You have held faith in the worst of times even as we are still reeling from Ferguson, Missouri, and Trayvon Martin and too many school shootings to recount.

Some days it’s hard to believe that the arc of the moral universe is ever going to bend, but this Coalition keeps us on course, and remind us in the words of Abraham Lincoln that “To sin by silence makes cowards of men.” This Coalition helps us all be brave, to stand up, to speak out, and to not be moved.

Your mission is more than an act of faith, or a statement of hope in a noble cause. It’s a real vow, a pledge of allegiance, and a promise to help us reclaim our humanity and to live in a civilized world.

So you have great reason to celebrate tonight and on the occasion of your 40th anniversary I salute each one of you–and none more so than your founder, Mike Beard, the man who brought us together. Mike marched with Martin Luther King and he worked for John F. Kennedy. He saw in both men the best hopes for America, and when both were struck down by gun violence, Mike found his cause and this Coalition. For those of us who never marched with Dr. King and never knew President Kennedy, Mike has bound us to their legacies, and for that we owe him our deepest thanks.

Kitty Kelley donated copies of Let Freedom Ring for those attending the Celebration, with a letter from her enclosed:

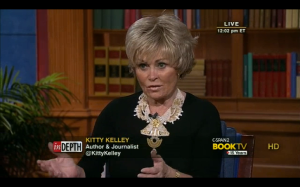

Kitty Kelley on Book-TV

Kitty Kelley appeared on C-Span2’s Book-TV “In Depth” program on Sunday, Nov. 3, 2013, answering questions from host Peter Slen and from viewers for three hours. The show may be viewed online here.

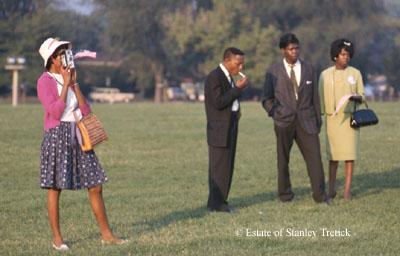

The March to the Dream

by Kitty Kelley

President Kennedy had to be pushed but after two bloody summers of Freedom Riders, television coverage of Bull Connors’ police dogs chewing children to bits, police men clubbing peaceful demonstrators and fire hoses slamming children against jagged brick buildings, leaving them torn and bleeding, JFK found his voice. He watched with disgust as Alabama Governor George Wallace, who had pledged “Segregation now. Segregation tomorrow. Segregation forever,” threatened to stand in the school house door to prevent two black students from integrating the state’s all-white university. That evening, June 11, 1963, John F. Kennedy ennobled his presidency with an address to the nation on equal rights:

President Kennedy had to be pushed but after two bloody summers of Freedom Riders, television coverage of Bull Connors’ police dogs chewing children to bits, police men clubbing peaceful demonstrators and fire hoses slamming children against jagged brick buildings, leaving them torn and bleeding, JFK found his voice. He watched with disgust as Alabama Governor George Wallace, who had pledged “Segregation now. Segregation tomorrow. Segregation forever,” threatened to stand in the school house door to prevent two black students from integrating the state’s all-white university. That evening, June 11, 1963, John F. Kennedy ennobled his presidency with an address to the nation on equal rights:

We are confronted primarily with a moral issue. It is as old as the Scriptures and as clear as the American Constitution…. If an American, because his skin is dark, cannot eat lunch in a restaurant open to the public, if he cannot send his children to the best schools available, if he cannot vote for the public officials who represent him…then who among us would be content to have the color of his skin changed? Who among us would then be content with counsels of patience and delay?

Next week I shall ask the Congress of the United States to make a commitment it has not fully made in this country to the proposition that race has no place in American life or law.

The President’s approval plummeted from 60 to 47 percent after his speech, and he and his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, began counseling “patience and delay,” pleading with Civil Rights leaders to call off their scheduled March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Fearing violence and re-election in 1964, the administration said the March would do more harm than good. “We want success in Congress, not a big show at the Capital,” said the President.

The President’s approval plummeted from 60 to 47 percent after his speech, and he and his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, began counseling “patience and delay,” pleading with Civil Rights leaders to call off their scheduled March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Fearing violence and re-election in 1964, the administration said the March would do more harm than good. “We want success in Congress, not a big show at the Capital,” said the President.

Kennedy summoned Civil Rights leaders to the White House to try to dissuade them but they remained resolute. The President relented and then called his brother: “Well, if we can’t stop them, we’ll run the damned thing.”

The March organizers agreed to demonstrate on a Wednesday so people would get back to their jobs and not stay the week-end. Parade permits were granted from 9 a.m to 5 p.m so that marchers would leave the city before dark. Schools, bars, restaurants and stores were closed. All elective surgeries in area hospitals were cancelled to free up 340 beds for riot-related emergencies.  The DC National Guard spent the summer training for riot duty and 2400 Guardsmen were sworn in as “special officers” with temporary arrest power. The city, including leaders like Mrs. Agnes E. Meyer, whose family owned The Washington Post and Newsweek, predicted “catastrophic outbreaks of violence, bloodshed and property damage.” The government closed the day of the March and federal employees were told to stay home.

The DC National Guard spent the summer training for riot duty and 2400 Guardsmen were sworn in as “special officers” with temporary arrest power. The city, including leaders like Mrs. Agnes E. Meyer, whose family owned The Washington Post and Newsweek, predicted “catastrophic outbreaks of violence, bloodshed and property damage.” The government closed the day of the March and federal employees were told to stay home.

The comedian Dick Gregory was amused by the fears of the white establishment. “I know the senators and congressmen are scared of what’s going to happen,” he said. “[But] I’ll tell you what’s going to happen. It’s going to be a great Sunday picnic.” To the Kennedy administration it looked like it was going to be a great big political fiasco.

Weeks in advance, the March, set for August 28, 1963, became global news as Civil Rights activists around the world announced that they, too, would march in Berlin, Munich, Amsterdam, London, Oslo, Madrid, The Hague, Tel Aviv, Cairo, Toronto, and Kingston, Jamaica.  Celebrities chartered planes from Hollywood’s progressive community, including Harry Belafonte, Paul Newman, Marlon Brando, Gregory Peck, Billy Eckstein, Lena Horne, Sidney Poitier, Sammy Davis, Jr., Tony Bennett, even Charleton Heston. Burt Lancaster flew from his movie location in Paris, and the dancer and jazz singer Josephine Baker arrived from France in her Free French uniform.

Celebrities chartered planes from Hollywood’s progressive community, including Harry Belafonte, Paul Newman, Marlon Brando, Gregory Peck, Billy Eckstein, Lena Horne, Sidney Poitier, Sammy Davis, Jr., Tony Bennett, even Charleton Heston. Burt Lancaster flew from his movie location in Paris, and the dancer and jazz singer Josephine Baker arrived from France in her Free French uniform.

Even with unprecedented police presence on the Mall, the President was so concerned about hot rhetoric stirring the crowds to violence that he positioned one of his advance men behind the sound system at the Lincoln Memorial ready to flip a special switch to cut the public address system, if necessary, and play a recording of Mahalia Jackson singing, “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands.”

The day dawned with Washington’s usual summer swamp humidity but most of the 250,000 marchers arrived in their Sunday best. Women donned hats and high heels; men wore white shirts and ties. They dressed for church; their mission was religious—to heal sick hearts and open closed minds.

They marched and sang and swayed to the soaring sounds of the Freedom Singers and Odetta and Marian Anderson; they sat ten- deep at the Reflecting Pool, many dangling their feet in the water like pilgrims who once gathered at the Sea of Galilee.

They cheered the speakers, and then they rose and roared in unison for the spell-binding finale of Martin Luther King, Jr., who had come to tell them about his dream for America “that one day the nation will rise up and live out the true meaning

of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’”

of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’”

The vast throng of humanity erupted into thunderous applause with each crescendo of Dr. King’s dream. In the rising cadence of a master spell-binder, he told America that if it was to become a great nation, it must make the dream of freedom come true for its black citizens. Even President Kennedy, watching on television, was transfixed. “He’s good. He’s damn good.”

The President had refused to participate in the March, but he invited the Civil Rights leaders to the White House at the end of the day. He greeted Dr. King by shaking his hand and saying, “I have a dream.”

Bubbling over with the success of the day which had occurred without one incident of violence, the President told reporters that he was edified by the speeches, the singing, the crowds—the entire event. “The nation can be properly proud of this march,” he said.

Photos from Let Freedom Ring: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the March on Washington, ©Estate of Stanley Tretick, used with permission.

Buy: Amazon Barnes & Noble Books-A-Million Apple IndieBound

Cross-posted from Huffington Post

Rose Kennedy: The Life and Times of a Political Matriarch

by Kitty Kelley

Anyone who has followed the Kennedys knows the bar is high for books on the subject. Having been inundated for the past 50 years with hundreds of biographies and memoirs and profiles about the spellbinding mystique of John Fitzgerald Kennedy, his family and his thousand days as the country’s first Irish-Catholic president, we expect each publication to bring something new and fresh to add to our understanding of the family that refashioned politics in the 20th century.

Anyone who has followed the Kennedys knows the bar is high for books on the subject. Having been inundated for the past 50 years with hundreds of biographies and memoirs and profiles about the spellbinding mystique of John Fitzgerald Kennedy, his family and his thousand days as the country’s first Irish-Catholic president, we expect each publication to bring something new and fresh to add to our understanding of the family that refashioned politics in the 20th century.

Serious historians (Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., William Manchester, James MacGregor Burns, Nigel Hamilton), journalists (Seymour Hersh, Jack Newfield, Warren Rogers), conspiracy theorists (Jim Garrison), commercial clip-and-pasters (Laurence Leamer, Christopher Anderson) and friends (Paul “Red” Fay, Benjamin C. Bradlee) have tried to capture the firefly magic of the Kennedys, while antagonists (Victor Lasky, Ralph de Taledano) have tried to puncture their myth.

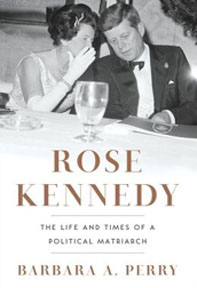

So now comes Barbara A. Perry with Rose Kennedy: The Life and Times of a Political Matriarch, who promises to deliver “the definitive biography” of the woman whose iron-fisted image-making produced the mystique that continues to endure. When the John F. Kennedy Library released the papers of the president’s mother (300 boxes) in 2006, Perry, a senior fellow in presidential oral history at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center in Charlottesville, was first in line, but, alas, Rose had no secrets beyond the few she revealed in her 1974 memoir, Times to Remember. As a biographer Perry was challenged. After six years of research and writing, she bowed to the obvious: With nothing new, she went for nuance. Her text is well written and her bibliography shows research, but there is no gold in the mine.

Her book cover, though, is perfect, absolutely perfect, because it captures the essence of Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy. The black-and-white photograph shows a woman who later died at the age of 104 after living her life by the black-and-white strictures of the Catholic Church, pre-Vatican II. Still glamorous at the age of 73, she is sitting next to the handsome president at a White House state dinner in 1963. She is acting as her son’s hostess because the first lady is away on one of her many vacations, similar to the ones Rose took for six to eight weeks at a time to get away from the clamor of her large family, and possibly, according to her biographer, as a means of Church-approved birth control. Rose is wearing the Molyneux gown she wore when she was 48 and her husband, Joseph P. Kennedy, was presented to the king and queen of England as the U.S. ambassador to the Court of St. James. That was the crowning glory of Rose’s life: To be accepted by British royalty was beyond the biggest dreams of a little girl from Dorchester, Mass.

Her book cover, though, is perfect, absolutely perfect, because it captures the essence of Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy. The black-and-white photograph shows a woman who later died at the age of 104 after living her life by the black-and-white strictures of the Catholic Church, pre-Vatican II. Still glamorous at the age of 73, she is sitting next to the handsome president at a White House state dinner in 1963. She is acting as her son’s hostess because the first lady is away on one of her many vacations, similar to the ones Rose took for six to eight weeks at a time to get away from the clamor of her large family, and possibly, according to her biographer, as a means of Church-approved birth control. Rose is wearing the Molyneux gown she wore when she was 48 and her husband, Joseph P. Kennedy, was presented to the king and queen of England as the U.S. ambassador to the Court of St. James. That was the crowning glory of Rose’s life: To be accepted by British royalty was beyond the biggest dreams of a little girl from Dorchester, Mass.

Bejeweled with two diamond clips in her hair, diamonds dripping from her ears, a triple strand of pearls the size of grapes circling her unlined neck and a bracelet of diamonds wrapped around her arm, which is encased in a long white kid-leather glove, Rose is whispering in her son’s ear.  Ever the canny pol, she covers her mouth so the photographer cannot catch a candid shot. (“I do not like candid pictures,” she said. “They are so unattractive.”)

Ever the canny pol, she covers her mouth so the photographer cannot catch a candid shot. (“I do not like candid pictures,” she said. “They are so unattractive.”)

Oh, did I mention that the Molyneux gown was sleeveless? This is a detail Rose would want to have emphasized because she prided herself on her petite figure and frequently said that after having nine children she could still wear a size 8. Her frenetic exercise routine of swimming in the ocean every day, playing golf, walking miles, eating sparingly and rarely drinking had left her sleek and svelte with tanned, taut arms.

Appearances ruled Rose, and nothing mattered to her as much as how one looked — in person and in pictures. She made her children line up for daily inspections so she could see if their shoes were shined and their buttons attached. She saw each child as a reflection of herself and of the family name her husband was making famous on Wall Street and in Hollywood, so she strove for perfection, demanding it of herself and everyone around her. A martinet mother, she insisted her children brush their teeth three times a day and say their prayers every night. They were instructed to make meals on time or go without eating, and en route to the dining room they were required to check the bulletin board for the topics of current affairs that were to be discussed at dinner. Rose was the parent in charge of their childhood. When they became young adults her husband took over, but as one daughter said, “Dad gave us many lovely things but mother gave us our character.”

Despite her foibles and her husband’s philandering Rose relied on her strong religious faith to survive the worst tragedies of her life, and she managed to produce an extraordinary family of sons and daughters, who cared for each other, supported each other and remained close throughout their lives — and that is a mother’s finest legacy. Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy is an admirable subject but one that left her admiring biographer empty-handed.

Kitty Kelley’s seven biographies include Jackie Oh! (1978), the first book to reveal that the former first lady suffered from depression and was treated with electroshock therapy; it also reported for the first time that Rosemary Kennedy survived the mangled lobotomy her father had ordered in hopes of reversing her mental retardation. In 1988, People published Kelley’s story detailing President Kennedy’s affair with a woman who carried his messages to her other lover, mobster Sam Giancana.

Kitty Kelley’s seven biographies include Jackie Oh! (1978), the first book to reveal that the former first lady suffered from depression and was treated with electroshock therapy; it also reported for the first time that Rosemary Kennedy survived the mangled lobotomy her father had ordered in hopes of reversing her mental retardation. In 1988, People published Kelley’s story detailing President Kennedy’s affair with a woman who carried his messages to her other lover, mobster Sam Giancana.

Cross-posted with Washington Independent Review of Books.

Photos from Capturing Camelot ©Estate of Stanley Tretick, used with permission.

Obama and the Legacy of Camelot

by Kitty Kelley

When Caroline Kennedy endorsed Barak Obama in 2008 as her father’s rightful heir she laid upon him the mantle of Camelot, and the enduring mystique of John F. Kennedy, who, according to polls, continues to be America’s most beloved president. Comparisons between the 35th and 44th presidents have been inevitable, and while there are striking similarities between the two men, there are also distinguishing differences.

Both rose to the nation’s highest office as junior U.S. Senators with scant legislative achievements to their credit. The man from Massachusetts served three terms in the House of Representatives before he won his Senate seat in 1952 and began campaigning for national office, running for Vice President in 1956 and for President in 1960. Obama, a state legislator in Illinois for seven years, began his run for the White House shortly after being elected to the Senate. Both men broke the barriers of bigotry to reach the highest office in the land–Kennedy as the first Roman Catholic; Obama as the first African American.

Erudite Ivy Leaguers, each seemed blessed with the gift of prose. Kennedy wrote three books, and won a Pulitzer Prize for Profiles in Courage; Obama made millions writing his best-selling memoir, Dreams from My Father. As a Boston scion and Harvard graduate, JFK. always smarted at being rejected for a seat on the Harvard Board of Overseers; Obama left Harvard with the distinction of having been the first person of color to be elected president of the Harvard Law Review.

Both men possessed extraordinary talents for oratory and inspired their generations with the poetry of hope–“the thing,” Emily Dickinson described, “with feathers that perches in the soul.” Their messages resounded for a nation grown restless after eight years of a Republican administration. Each man came to the presidency with their party in control of Congress, and each used that power to effect sweeping change. Kennedy introduced the most comprehensive and far-reaching civil rights bill, which was not passed on his watch, but became law under his successor. Obama signed the Affordable Care Act of 2010 which reformed health care to provide insurance for all Americans. Kennedy ordered federal departments and agencies to end discrimination against women in appointments and promotions; Obama signed the Lilly Ledbetter Act to provide fair pay in the work place. In addition, he succeeded in getting a measure passed to end discrimination against gays in the military.

Both men possessed extraordinary talents for oratory and inspired their generations with the poetry of hope–“the thing,” Emily Dickinson described, “with feathers that perches in the soul.” Their messages resounded for a nation grown restless after eight years of a Republican administration. Each man came to the presidency with their party in control of Congress, and each used that power to effect sweeping change. Kennedy introduced the most comprehensive and far-reaching civil rights bill, which was not passed on his watch, but became law under his successor. Obama signed the Affordable Care Act of 2010 which reformed health care to provide insurance for all Americans. Kennedy ordered federal departments and agencies to end discrimination against women in appointments and promotions; Obama signed the Lilly Ledbetter Act to provide fair pay in the work place. In addition, he succeeded in getting a measure passed to end discrimination against gays in the military.

Both Kennedy and Obama exuded a dash of glamour in their roles as Commander-in-Chief and became the darlings of Hollywood. As President, each brought to the White House a fashionable and accomplished First Lady, two adorable young children, and scene-stealing pets. Yet as beloved as each became, both men stirred ferocious passions and dangerous threats from extremists who accused them of treason.

As notable as their similarities are the differences which define and separate them. Kennedy grew up with immense wealth and the high expectations and powerful connections of his father, the former Ambassador to the Court of St. James, who was the 14th richest man in America in 1960, worth more than $400 million. Obama, a fatherless child, forged his way on the wings of a single working mother, who wandered the world and left her son to the loving care of her parents. As a young man he borrowed thousands of dollars to finance his education and was not able to repay his student loans until he was 43 years old.

Both elusive men, Kennedy and Obama cared mightily about their public image, not an insignificant concern for politicians. Kennedy, who worried about being portrayed as a rich man’s dilettante son, would not allow photographs inside Air Force One, saying it would look like a playboy’s luxury. Obama made sure cameras never caught him smoking cigarettes. Each understood the mesmerizing power of appearances and knew as the actor Melvyn Douglas says in the film Hud, “Little by little the look of the country changes just by looking at the men we admire.”

Both presidents tangled with corporate America and drew the ire of big business. Kennedy blasted the steel industry in 1962, saying their price increase was “unjustifiable and irresponsible.” Obama, a community organizer, championed the middle class, challenging Wall Street when he enacted financial regulatory reform, and demanded that the richest Americans to pay their full share of taxes.

Each had to find his way through military quagmires left by their predecessors. Kennedy was haunted by the Bay of Pigs invasion but carried the country through the Cuban Missile crisis. He later increased the number of US military advisers to South Vietnam to more than 16,000. Obama came to the White House determined to end the Iraq War which he did by December 2011. After sending 33,000 more U.S. soldiers to Afghanistan as part of a strategy to downsize the American commitment there, he vowed to end that war by 2014.

Politically, both men made judicious choices in their running mates, but Kennedy never gave Lyndon Baines Johnson the full partnership that Obama accorded to Joe Biden.

Kennedy left behind the Peace Corps, the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty and the promise of a man on the moon within the decade. Obama’s legacy must be left to the historians of tomorrow but at the dawn of his second term, following an inauguration that coincided with the fiftieth anniversary of President Kennedy’s last year in office, it is reassuring to believe that each man dedicated his presidency to setting the country’s course true north.

(Photo: President Barack Obama looks at a portrait of John F. Kennedy by Aaron Shikler, taken by official White House photographer Pete Souza)

Cross-posted from Huffington Post

The Patriarch

by Kitty Kelley

The Patriarch (Penguin Press) is the perfect title for the life story of Joseph Patrick Kennedy. It resounds with the drama of rolling drums to introduce a paterfamilias who created one of America’s most powerful political dynasties. The author, David Nasaw, was hand-picked by the Kennedys and given access to all the family’s personal papers, including the senior Kennedy’s letters, which comprise the ballast of this biography.

The Patriarch (Penguin Press) is the perfect title for the life story of Joseph Patrick Kennedy. It resounds with the drama of rolling drums to introduce a paterfamilias who created one of America’s most powerful political dynasties. The author, David Nasaw, was hand-picked by the Kennedys and given access to all the family’s personal papers, including the senior Kennedy’s letters, which comprise the ballast of this biography.

Such access is no surprise for an historian on the faculty of the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, where he is the Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. Distinguished Professor of American History. As President Kennedy’s in-house historian and the devoted biographer of Robert F. Kennedy, Schlesinger was no incidental contributor to the myths of Camelot, but this is not to say that Nasaw’s biography is hagiography. He covers the light as well as the dark corners of Joseph P. Kennedy’s complicated persona. But having written biographies of William Randolph Hearst and Andrew Carnegie, Nasaw prefers to describe himself “as an academic historian, not a biographer,” which may be why his narrative reads like an orange squeezed dry. For 896 pages he follows the chronology of Joseph P. Kennedy’s life (1888-1969) as methodically as a metronome, and documents all the facts with footnotes. Yet one wishes there had been a little more poet in the professor.

Joseph Patrick Kennedy was born to all the prosperity that East Boston allowed Irish-Catholics in the 19th-century, which was fathoms below the social acceptance accorded “proper Bostonians,” as Kennedy referred to his Protestant peers. Blessed with charm and intelligence, he was determined to break down the wall that separated former “bog-dwellers” from their Brahmin “betters.” This became his life’s ambition and drove him to make his son the country’s first Irish-Catholic president.

After attending Boston Latin, then the best public school in the country, young Joe was accepted at Harvard. There he excelled in athletics and networking, which, he impressed upon his sons in frequent letters, was the purpose of Harvard. “You will have a great start on any of your contemporaries and you should be able to keep up very important contacts,” he wrote. Befriending “the topmost people,” as he called them, became a lifetime priority.

After graduating from Harvard, Kennedy was unable to get a white-shoe job on Wall Street, so he became a bank examiner in Massachusetts and mastered the intricacies of an unregulated stock market, eventually earning a reputation as a “rapacious plunger.” He pounced on bankruptcies, foreclosures and receiverships, and used insider knowledge to buy and sell stock, all of which would later become illegal. As president of an East Boston bank he borrowed heavily from the bank to finance his trades, and borrowed even more to invest in commercial real estate. In 1945 he bought the Merchandise Mart in Chicago for $13 million. The family sold the Mart in 1998 for $630 million.

Kennedy also made huge profits from reorganizing and refinancing several Hollywood studios. During this time he managed the career of the film star Gloria Swanson, who became his mistress and traveled with him on his family vacations. A practicing Catholic, he also traveled with his own confessor. Nasaw reports that Kennedy spent little of his married life with his wife, Rose, who ignored his pursuit of other women just as her mother had done when her husband, Honey Fitz, the mayor of Boston, was caught with a cigarette girl named “Toodles.”

Making multimillions during the bull market of the 1920s, Kennedy had become one of the 14 richest men in America by 1957. By then he had established trust funds (each worth $90 million in 1960) for his nine children and each of their children. He provided his family with a luxe life of Rolls Royces, yachts, villas on the French Riviera, Hollywood mansions, an estate in Palm Beach, a summer compound in Cape Cod and a suite in the Carlyle Hotel.

In addition, Kennedy bought his own publicity machine. His legion of press agents included the respected New York Times columnist Arthur Krock, who was put on a secret annual retainer to do Kennedy’s bidding whenever he wanted positive coverage for himself or his family in the nation’s most influential newspaper.

Nasaw explores in detail Joseph Kennedy’s virulent anti-Semitism and his role as U.S. Ambassador to the Court of St. James when he aligned himself with Neville Chamberlain to appease Hitler. His isolationist views forced him to resign as ambassador and made him anathema to most Americans, but Kennedy never apologized. Even after the allied victory Kennedy told Winston Churchill that the war had not been worth the lives lost, including Kennedy’s first-born son and namesake, and the destroyed European economy.

Those familiar with Kennedy lore might be amused to learn that J.F.K. was considered by his father to be “the family’s problem child.” So concerned was Kennedy about his second son’s messy appearance, dilatory study habits and poor grades that he beseeched the headmaster at Choate to intervene and “do something about Jack.” Yet it was Joe Kennedy, not Rose, who cancelled vacations to stay home to nurse J.F.K. through many of his childhood illnesses.

What emerges from this biography is that the anti-Semitic, pro-Nazi, philandering wheeler-dealer was — first, last and always — a ferociously loving father who put his sons and daughters above all else. As he told President Roosevelt: “I did not want a position in the government unless it really meant some prestige to my family.”

Cross-posted from Washington Independent Review of Books.