Book Review

I Am, I Am, I Am

by Kitty Kelley

Before Maggie O’Farrell wrote Hamnet, her award-winning 2020 novel that reimagines the life and death of Shakespeare’s only son, she examined her own life and death in a memoir entitled I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death.

Before Maggie O’Farrell wrote Hamnet, her award-winning 2020 novel that reimagines the life and death of Shakespeare’s only son, she examined her own life and death in a memoir entitled I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death.

While most people fear what W.C. Fields called “the man in the bright nightgown,” O’Farrell claims to be sanguine about death, and she makes her case as someone who has outwitted the scythe 17 times in 49 years. Still, if not for her luminous writing, the book might not beckon.

O’Farrell takes her title from Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, a fictional descent into madness in which the protagonist survives suicide and lives to feel her brave heart beat evenly: “I took a deep breath and listened to the old brag of my heart: I am, I am, I am.” That regular rhythm signals life, and O’Farrell’s book offers an affirming message about escaping death.

In 17 short chapters about the 17 body parts affected by her own near-fatal experiences, O’Farrell hopscotches across time to recount her gambols with the Grim Reaper, including “Neck (1990),” “Body and Bloodstream (2005),” and “Cerebellum (1980).” Each essay is introduced with a sketch of the part — neck or body and bloodstream or brain — to be discussed.

She thinks there is nothing unique about a near-death experience and claims they’re not rare:

“[E]veryone, I would venture, has had them…perhaps without even realizing it. The brush of a van too close to your bicycle, the tired medic who realizes that a dosage ought to be checked one final time, the driver who has drunk too much…the aeroplane not caught, the virus never inhaled.”

As a child, she writes, she was an escapologist. “I ran, scarpered, dashed off, legged it whenever I had the chance…I wanted to know, wanted to see, what was around the next corner, beyond the bend.”

At the age of 8, the super-charged little girl’s life changed forever: She woke up with a headache and could not walk. She had contracted encephalitis. She was close to death and hospitalized for weeks with fever, pain, and immobility. Suddenly, she was a child who could barely hold a pen, who had lost the ability to run, ride a bike, catch a ball, feed herself, swim, climb stairs, and skip. She was a child who traveled everywhere in a humiliating, outsized buggy.

From the hospital, O’Farrell was blanketed like a baby and carried home to spend many more months in bed, and then a wheelchair, followed by hydrotherapy and physiotherapy, and finally recovery. She recalls that searing experience as “the hinge on which my childhood swung”:

“Until that morning I woke up with a headache, I was one person, and after it, I was quite another. No more bolting along pavements for me, no more running away from home, no more running at all. I could never go back to the self I was before.”

Without self-pity, she recites the illness’ devastating aftereffects: As an adult, she loses her balance and can’t walk a straight line or stand on one foot. She frequently falls over, drops silverware, and cannot cycle long distances.

The self she became — her after-self — was dogged by disappointment, dashed dreams, and near death. She loses her track to a Ph.D. and an academic career at the age of 21 because of inadequate grades; she nearly drowns in a riptide; she is held up at knife point; and she bolts from a live-in boyfriend after finding a flesh-colored bra under the bed that is not hers.

After the latter incident, she waits “the requisite time” for a virus to appear, grabs her gay friend, and insists they go to a clinic to get tested. The receptionist gives each a page to fill in about previous sexual encounters. Her friend looks at the form and delivers the only risible line in this book: “Do you think you’re allowed to ask for extra paper?” he asks “a little too aloud.” (Needing comic relief from O’Farrell’s unremitting woes, I, too, laughed a little too aloud.)

O’Farrell writes luscious sentences about grim subjects, particularly her attempts to conceive, only to have to cope with a wretched miscarriage:

“Something is moving within me, deep in the coiled channels of my stomach, something with claws, with fangs, and evil intent…It is as though I have swallowed a demon, a restive one that turns and fidgets, scraping its scales against my innards.”

She suffers so many miscarriages that she and her husband refer to the doctor’s office as “the bad-news room.” Later, when she finally carries a pregnancy to term, she spends three agonizing days in labor — an excruciating experience considering the average labor for a first-time mother is six to 15 hours.

She faults “the highly politicized arena of elective Caesareans in the U.K.” and excoriates as a butcher the British doctor who kept denying her a C-section. She describes the surgery in such visceral detail that you cringe, almost feeling the surgeon slice across her stomach and the nurses wrestling and grappling and clutching and heaving, until finally her body ruptures, spraying blood everywhere. Another near-death experience, but one that produces her first child.

All the literary reading that O’Farrell poured into her doctoral studies is on fine display in these pages. Among others, she references Shakespeare, Thomas Hardy, Seamus Heaney, Arthur Miller, Hilary Mantel, Robert Frost, Mark Twain, and Andrew Marvell’s “winged chariot,” which carries her into elegant riffs with a scholar’s vocabulary:

“The wave turns me over…like St. Catherine in her wheel”; “like Brueghel’s Icarus falling into the waves”; “the stifling anhydrous scent of sawdust”; “with a tiny rhomboid of garden”; “watched from the ceiling by a leucistic gecko…”

In I Am, I Am, I Am, Maggie O’Farrell rings all the bells for impressive prose, albeit on a subject of little poetry.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Widowish

by Kitty Kelley

Death never knocks gently except for those lucky few who’ve lived long, full lives and go to bed one night to wake up with the angels. For everyone else, the knock on the door is fraught, and particularly devastating for those who are young and in the happy throes of living.

Death never knocks gently except for those lucky few who’ve lived long, full lives and go to bed one night to wake up with the angels. For everyone else, the knock on the door is fraught, and particularly devastating for those who are young and in the happy throes of living.

Death began stalking Joel Gould shortly after he arrived at the emergency room with flu-like symptoms. He and his wife, Melissa, had been dealing with his multiple sclerosis for a few years, as the autoimmune disease gradually affected his balance and muscular control, leaving him unable to play basketball, ride his bike, or even walk to work.

They’d told their young daughter he had MS — withholding the frightening specifics — but kept the diagnosis secret from the rest of their family and friends in order to avoid questions with morose answers.

Three days after Joel entered that hospital, he was put in the intensive care unit and placed on life support while doctors told Melissa that he was “gravely ill.” She screamed at them. “We’re in a hospital. You’re all doctors. If Joel is sick, make him better…We have a thirteen year old daughter.”

Upon the recommendation of their family doctor, Melissa moved her husband to a teaching hospital where specialists tried to determine his worsening condition. “He had another MRI. A brain angiogram. A spinal tap. Several EEGs to monitor brain activity. More blood work. More cultures.” Finally, they diagnosed West Nile virus, which had decimated Joel’s compromised immune system, leaving him paralyzed and brain dead.

One of the doctors asked Melissa what she’d meant when she’d said quality of life was important to her husband. “Having just turned fifty years old, he did not want to end up in diapers,” she writes.

The doctor then asked if that meant Joel wanted to be someone capable of living independently.

“Yes, absolutely,” she said.

“Well…it looks that as of now, the kind of recovery we can hope for is that he may be able to hold a comb one day. But he wouldn’t know what to do with it.”

Death had just rammed open the door of Melissa Gould’s life, leaving her bereft and crazed with grief. Knowing her husband would never recover, she allowed him to be taken off life support, but, at the age of 46, refused to be defined as a widow. The word revolted her:

“Widow once described a much older woman. Old, wrinkled, tragic. Wearing black. Maybe even a veil…[I was] a mom with blonde highlights going to yoga, picking up her daughter from school, buying groceries at Trader Joe’s…I didn’t look like a widow.”

To her, “widow” was an ugly word hanging from the mottled neck of a woman with grey hair and yellow teeth. Even now, years after her husband’s death, she called fellow widows and widowers “wisters” — widow sisters and widow misters. Hence, she titled her memoir Widowish, as if a little suffix can soften the whiplash.

Perhaps this is understandable for a pop-culture princess from Southern California like Melissa, who writes about regular hikes on a hill she calls “the Clooney,” because it’s near an L.A. house owned by George Clooney. Sometimes she makes the climb with her “bestie,” who’s “the Gayle to my Oprah.”

She defines herself as “simply Jew-ish,” writing: “Outside of my liberal and cultural connection to Judaism, I just didn’t connect.” Her Jewish husband connected completely, however, which is why she’d called a rabbi to his bedside. “I knew Joel would have welcomed a visit without hesitation.”

Her devotion to her spouse is undeniable as she weaves the story of their marriage into surviving without it. She writes that when they met, she felt like she’d hit the trifecta. “He was cool. He was funny. He was Jewish.”

He was also in a committed relationship, but they bonded over their shared passion for music. When she told him she was leaving for Seattle to write for a television show, he summoned his best impersonation of Daniel Day-Lewis in “The Last of the Mohicans”: “Stay alive, no matter what occurs! I will find you!”

She became enthralled with Seattle as “the epicenter of the biggest shift the music business had seen in decades — grunge — Kurt Cobain was still alive…I was in heaven.” A few months later, Joel, also in the music business and recently separated, showed up. “We didn’t stop kissing the entire few days he was in Seattle.”

They married, moved back to California, and had one child, although they’d hoped to have many. Melissa writes seamlessly about caring for their daughter after Joel’s death, keeping to the youngster’s schedule, getting her to school on time, making her meals, helping with homework, and curling up in bed with her every night “to talk about Daddy.”

Few people forge through the miasma of grief without help, which is why believers light candles and liquor stores open early. Melissa found her way by watching “Real Housewives” religiously, listening to TV evangelist Joel Osteen preach his “attitude of gratitude” gospel, and embracing New Thought guru Iyanla Vanzant as her life coach.

“Grief is personal and private,” Melissa writes, but hers never was. She shared it with her friends, her family, a man at the car wash, her hairdresser, and all the cashiers at the supermarket. “I was in midlife, barefoot in shiva clothes and a blowout. I felt compelled to tell people I was a widow because I didn’t look like one.” She wrote about her grief in the New York Times and the Huffington Post, which led finally to this book.

Searching for guidance, she went to a “highly recommended” psychic named Candy. Melissa presented Joel’s watch and photograph because “it helps channel or receive information.” Within minutes, Candy claimed she was connecting with Melissa’s dead husband. She said there would be a new man in her life soon with a son, and that Joel approved of the relationship.

“That’s what he wants me to tell you,” said Candy.

Melissa writes that she laughed off the prediction until she met Marcos — and then his son — a few weeks later. Six months after kissing her husband goodbye, Melissa begins “to live again” by dating Marcos. At this point, some “wisters” might be envious, while others may tsk-tsk, but Melissa Gould is a Hollywood writer who has read Cinderella. She knows the value of a happily-ever-after ending.

She and Marcos and their children now live together near Simi Valley, where Melissa runs a writing workshop at Camp Widow, part of a nonprofit called Soaring Spirits International, where she guides people in healing by exploring the unexpected realities of being a widow. Yes, she can finally face that word without the “ish.”

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Robert E. Lee and Me

by Kitty Kelley

Early in the Civil War, the Union Army seized “Arlington” — Robert E. Lee’s 1,100-acre estate across the Potomac from Washington, DC — and used it to headquarter federal troops. Lee never returned to his home, but he sued his country for damages after the war and collected more than $4 million.

Early in the Civil War, the Union Army seized “Arlington” — Robert E. Lee’s 1,100-acre estate across the Potomac from Washington, DC — and used it to headquarter federal troops. Lee never returned to his home, but he sued his country for damages after the war and collected more than $4 million.

When debate about the property seizure reached the U.S. Senate, Charles Sumner, who led that body’s anti-slavery forces, railed against the slaveholding Confederate general, saying: “I hand him over to the avenging pen of history.” That pen has now been wielded to dazzling effect by Ty Seidule in Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerner’s Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause.

Few others could write this book with such sterling credibility. Only a man of the South, a Virginian, and a soldier with a Ph.D. in history could so persuasively mount the case against a national hero, and label him a traitor. For even today, the image of Lee, who fought against his country to preserve slavery, is revered with monuments, parks, military bases, counties, roads, schools, ships, and universities named in his honor. Yet, armed with years of documented research, Seidule demonstrates that Lee, like Judas, was guilty of base betrayal.

“It’s an easy call,” he writes at the end of his stunning book, “because Lee resigned his commission, fought against his country, killed U.S. Army soldiers, and violated Article III, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution. Lee committed treason.”

It wasn’t always an easy call for Seidule, a retired U.S. Army brigadier general who taught at West Point for 16 years and spent many of those years trying to understand why America’s premier service academy had so many monuments honoring Lee. “I went to the archives and spent years studying…that process changed me. The history changed me. The archives changed me. The facts changed me.”

As a boy, Seidule read Meet Robert E. Lee, “my childhood bible.” And “growing up in Virginia I worshipped Lee, the Confederate general.” Seidule attended Washington and Lee University in Lexington City, Virginia, where Lee Chapel features a statue of the general lying on the altar, but nothing else: no hymnals, no Book of Common Prayer, and no Ten Commandments (as the first one is: “I Am the Lord Thy God and Thou Shalt Not Have False Gods Before Me”).

“My school worshipped Robert E. Lee, literally,” Seidule writes. “[He] was God, and his Confederate cause was the one true religion.” He admits, somewhat shamefully, that he, too, once believed “all the lies and tropes.”

Lee’s body lies in a white marble sarcophagus under Lee Chapel alongside the remains of his faithful steed, Traveller. Visitors place carrots and apples on the horse’s grave, along with pennies — “Always heads down. No one wanted to have the hated Lincoln’s face visible to Lee’s grave.”

While slavery was abolished in 1863, Seidule learned that slaveholders continue to be honored to this day. He reports that Confederate monuments at 34 cemeteries in the U.S. are kept up by the government at taxpayer expense. “Over the last ten years federal and state governments have paid more than $40 million to maintain memorials to Confederate treason and racism with only a pittance going to African American cemeteries from the slave era.” As an Army officer, he’s particularly irate about the monument at Arlington National Cemetery:

“That angers me the most because every year the President of the U.S. sends a wreath ensuring the Confederate monument there receives all the prestige of the U.S. government…among the 400,000 soldiers, sailors, airmen and marines buried on those hallowed grounds are my friends, colleagues and family.”

Most Confederate monuments, including those honoring Lee, were erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in the early 20th century to preserve the glorious myth of the Lost Cause — a Southern euphemism for inglorious defeat:

“[Those monuments have] the same purpose as lynching: to enforce white supremacy. It is no coincidence that most Confederate monuments went up between 1890-1920, the same period that lynching peaked in the South. Lynching and Confederate monuments served to tell African Americans they were second-class citizens.”

The United Daughters of the Confederacy sprayed perfume on the stench of slavery and fluttered swan’s-down fans as they fashioned the Civil War as “the war of Northern aggression.” Seidule rightly calls it the war over slavery, and most responsible historians agree. But the author admits that while the South lost the war, they won the battle for the narrative.

No one did more to promote that narrative — moonbeams and magnolias, happy slaves and beloved masters — than Margaret Mitchell, who wrote Gone with the Wind, which has sold over 30 million copies to become the second most-popular book in America, next to the Bible. As the poet Melvin Tolson (1895-1966) wrote, “[That book] is such a subtle lie that it will be swallowed as the truth by millions of whites and blacks alike.”

The most damning indictment against Robert E. Lee is found in his own letters, which refer to the Emancipation Proclamation as “a savage and brutal policy,” words that aptly describe Lee’s treatment of his slaves, as verified in testimony given by one enslaved worker who had tried to escape from “Arlington” with his sisters. They were captured and punished:

“[Lee] ordered his constable to lay [the whip] on well with fifty lashes for [the man] and twenty for his sisters. After the whippings on their bare backs, Lee ordered salt water poured over their lacerated flesh.”

Ty Seidule writes with the passion of a convert who’s seen the light and needs to shine it for other to save them from “the lies and tropes” that blinded him for so many years. Robert E. Lee and Me is a cri de coeur, one man’s journey to humanity and his salvation from the pernicious lies of white supremacy.

Crosssposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

(Kitty Kelley interview with Ty Seidule here.)

Henry Adams in Washington

by Kitty Kelley

If an academic book is one that can be taught in college, then Henry Adams in Washington: Linking the Personal and Public Lives of America’s Man of Letters succeeds. In fact, this book by Ormond Seavey, an English professor at George Washington University, reads like a semester’s course on why Henry Adams ought to be elevated to the pantheon of 19th-century writers alongside Mark Twain, Henry James, Edith Wharton, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry David Thoreau.

If an academic book is one that can be taught in college, then Henry Adams in Washington: Linking the Personal and Public Lives of America’s Man of Letters succeeds. In fact, this book by Ormond Seavey, an English professor at George Washington University, reads like a semester’s course on why Henry Adams ought to be elevated to the pantheon of 19th-century writers alongside Mark Twain, Henry James, Edith Wharton, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry David Thoreau.

Seavey maintains that Adams (1838-1918) has been deprived of his rightful place in the literary stratosphere and proposes restoration. He starts by stating that the writer’s nine volumes entitled History of the United States of America (1801-1817) “belong alongside the greatest works of American creative writers.”

Further, he asserts the books comprise “the greatest work of history composed by an American…yet…unacknowledged in its own country,” and he intends to bring Adams the recognition he feels he deserves in the U.S. The professor concedes some literary critics might disagree with him, but he presents his case with pedagogical fervor and a few too many convoluted sentences:

“[Adams’] Washington turns out to be an essentially imaginative construct whose dimensions and appearances correspond to what others experience except that he has converted those details into a complex notion somehow independent of the seemingly solid realities experienced, for example, by James Madison, John Randolph, Ulysses S. Grant, Henry Cabot Lodge, or Theodore Roosevelt.”

Seavey scores high on presenting Adams as a man of letters but falls short on illuminating the personal side of the man. Publicly, Adams was known as a Boston Brahmin with a prestigious lineage: President John Adams (1735-1826) was his great-grandfather, and President John Quincy Adams (1767-1848), his grandfather. He made his own mark as a noted historian and novelist.

Yet even 100 years after his death, the personal man remains elusive because, for reasons Seavey doesn’t explain or explore, Adams resisted transparency. Other than his multi-volume history, he refused to publish under his own name and sometimes went to great lengths to camouflage his authorship. Why remains unknown.

When Adams worked for his father, Charles Francis Adams Sr., in the House of Representatives, he wrote anonymously as the Washington correspondent for Charles Hale’s Boston Daily Advertiser. Later, when his father became Abraham Lincoln’s ambassador to the Court of St. James, Adams worked as his father’s private secretary and wrote anonymously as the London correspondent for the New York Times.

Was he anonymous because of conflicts of interest between working in politics while working as a journalist? Seavey doesn’t say; he simply describes Adams as “that master of conspiracies and disguises.”

After Adams married and moved to Washington, he wrote two novels, each one blanketed in secrecy: Democracy, which Seavey describes as “a novel disguised as autobiography,” was published anonymously, and Esther, which was published under the female pseudonym Frances Snow Compton.

Why the camouflage? Seavey suggests that Adams hid behind a skirt because he was unwilling to have his DC neighbors know he was the one exposing the city’s deficiencies. If his novels, based on real people, were published under his name, he may have jeopardized his social status in Washington, where he and his wife, Clover, John Hay and his wife, Clara, and Clarence King, a pioneering geologist and entrepreneur, formed an elite little club they called “The Five of Hearts,” the title of Patricia O’Toole’s spectacular 1990 biography, which was subtitled “An Intimate Portrait of Henry Adams and His Friends, 1880-1918.”

That loving quintet splintered on December 6, 1885, when Clover Adams, 42, committed suicide by swallowing potassium cyanide. The evening newspaper reported she had dropped dead from paralysis of the heart, which may have been strangely accurate, because the writings of others indicate she knew her husband had fallen in love with another woman, Elizabeth Sherman Cameron.

That Christmas, days after his wife’s death, Adams sent Cameron a piece of Clover’s favorite jewelry, requesting she “sometimes wear it, to remind you of her.” He had been writing Cameron passionate letters since 1883, two years before his wife took her life, and continued for the next 35 years of his life, although, according to Eugenia Kaledin’s The Education of Mrs. Henry Adams, their relationship was never consummated.

These personal details are ignored by Seavey, although available in the biography of Adams written by Ernest Samuels (1903-1996), who received the Parkman Prize, the Bancroft Prize, and the 1965 Pulitzer Prize for his three-volume study. Yet Samuels is not listed in Seavey’s bibliography and is only cited once in passing, a strange omission in a book purporting to link “the personal and public lives of America’s man of letters.”

These personal details are ignored by Seavey, although available in the biography of Adams written by Ernest Samuels (1903-1996), who received the Parkman Prize, the Bancroft Prize, and the 1965 Pulitzer Prize for his three-volume study. Yet Samuels is not listed in Seavey’s bibliography and is only cited once in passing, a strange omission in a book purporting to link “the personal and public lives of America’s man of letters.”

The most intriguing monument to the mystery of Adams is the bronze sculpture he commissioned in memory of his wife, frequently called “Grief.” “Henry Adams left it to August St. Gaudens to preserve forever the experience of [his] loss. Visitors to Rock Creek Cemetery [in Washington, DC] can see it for themselves. And that is all I am going to say about that,” Seavey writes.

The professor ends his book a few pages later, having shown in full the public life of Henry Adams but leaving his personal side in shadows, still detached and disparate.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

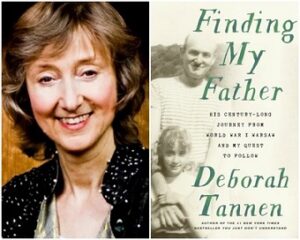

An Interview with Deborah Tannen

by Kitty Kelley

Deborah Tannen, a professor of linguistics at Georgetown University, has just published her 13th book, and first memoir, Finding My Father: His Century-long Journey from World War I Warsaw and My Quest to Follow. We recently discussed the new work.

You’ve written many books (including You Just Don’t Understand, You’re Wearing THAT?, You Were Always Mom’s Favorite!, and You’re the Only One I Can Tell) about how people express/hide themselves through language. How did the commercial success of those books enhance or detract from your position in academia?

You’ve written many books (including You Just Don’t Understand, You’re Wearing THAT?, You Were Always Mom’s Favorite!, and You’re the Only One I Can Tell) about how people express/hide themselves through language. How did the commercial success of those books enhance or detract from your position in academia?

My colleagues at Georgetown and in my discipline have been uniformly supportive of me and my academic, as well as my general-audience, writing. I feel I should add “kunnahurra,” which is how my mother pronounced the Yiddish expression one says to avoid jinxing good fortune.

How did writing this book about the father you adored affect you?

My father was the parent I felt an affinity for, the one I thought understood me. But when I was a child, he was rarely home. The strongest presence I felt in the house was his absence. The hours upon hours I spent talking to him about his life after he retired — I have 200 cassette tapes! — began to make up for that deep sense of longing. He also gave me mountains of written words: journals he kept before he married; letters he saved and copies of letters he wrote; and memories he wrote down for me, especially about his childhood in Warsaw (where he was born into a Hasidic family in 1908), but also about his life after he came to the U.S. in 1920. These all helped me see how his life was affected by and reflected the cataclysmic events of the 20th century: how WWI affected Warsaw’s Jews, immigration, the Depression, and anti-Semitism in both Poland and the U.S. between the wars.

My father’s father died of tuberculosis when he was very young — he never knew his father — so [my father] quit high school at 14 to support his mother and sister. Yet he became a lawyer, established the largest workers’ compensation firm in New York City, and ran for congress. Until I was in junior high, my father worked as a cutter in a coat factory. After that, my father was a partner in his own law firm. I always knew these outlines but had no idea how or why it happened that way, what it all meant, day to day, how he felt about it, or why it took him 30 years from passing the bar until he could support his family through law. Figuring it out gave me a clearer sense of how I was shaped by history, too.

Why do you think your father chose you to write his memoir rather than one of your two sisters? And has publication of this book affected your relationships within your family?

It was a no-brainer. I was already a published writer, having gotten a love of language and of writing from him. And my adoration was obvious. My sister Mimi once said, “I love Daddy, too, but I don’t think he’s God!” She and my sister Naomi have always been part of this project. I checked memories with them, and whenever I found something surprising, I’d share it with them. Our memories differ, of course. Naomi is six years older than Mimi and eight years older than me, so she had our father to herself when she was small. Naomi, like me, tended to idealize him and be critical of our mother. Mimi has been an invaluable reality check. She’ll point out when I’m judging our mother too harshly and letting our father off the hook.

As an immigrant from WWI Warsaw, your father did not have an easy life. His father died young; his mother sounds like a harridan; and he worked at over 60 jobs to support her and himself and his family. Yet he lived to be 98. To what besides good genes do you attribute his longevity?

Good luck. His and mine.

You discovered a secret relationship of your father’s and entitled one chapter “The Hidden Letters” after finding correspondence that he had secreted away for decades. Please describe.

Ah, yes, the woman I call Helen. She wasn’t a secret, but the fact that he’d saved her letters was. Both my parents spoke openly and casually about my mother’s “rival.” My father once said, “Your mother wasn’t my girlfriend. Helen was my girlfriend.” So why did he marry my mother and not his girlfriend? When he told me he’d saved Helen’s letters but didn’t know where they were, I longed to find them, to figure that out. I eventually did find them — along with copies of many letters he wrote to her! Reading their correspondence, I fell in love with Helen myself. I saw that my father’s relationship with her was romantic in a way his relationship with my mother wasn’t. And I was able to piece together the dramatic events that led to his marrying my mother. I felt I’d solved a mystery and learned a lot about relationships between women and men at the time, especially the fraught role played by virginity!

Your father was a communist, an atheist, and a Zionist. Can you say a bit about each and explain how each weaves into the other?

My father already identified as all three when he came to the U.S. at 12. He was influenced by the Bolshevik revolution through his mother’s youngest sister. Only six years older than my father, Magda was like a big sister he looked up to. Like many young people in every generation, she and her friends saw poverty and injustice and wanted to build a better world. Communism promised that would come when workers of the world unite and saw religion as a barrier to that solidarity. So atheism and communism went together. My father became disillusioned with communism but became an ever-more passionate supporter of Israel as he saw what happened to the members of his family who were still in Poland at the start of WWII. He remained a devout atheist with a deep and proud Jewish identity. When he was old, I asked, “Do you feel more Polish or American?” He replied, “I feel like a Jew.”

What advice would you give to your students about writing a memoir, particularly those who, unlike you, don’t have the advantage of hours and hours of taped interviews?

Talk to anyone you can find who knew your family or lived through similar times. Follow every trail wherever it takes you — to other people you can talk to, any documents you can find, and the infinite pathways now available on the internet. And write your own memories down for the next generation!

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

1957

by Kitty Kelley

Eric Burns writes books with long titles. His first, Broadcast Blues: Dispatches from the Twenty-Year War between a Television Reporter and His Medium, written in 1993, was a memoir of sorts. As an Emmy-winning correspondent for NBC News who later spent 10 years at Fox News before being fired, Burns knows the highs and lows of broadcasting. He’s since indicated that Fox is not a crucible of credibility, but rather “a cult.”

Eric Burns writes books with long titles. His first, Broadcast Blues: Dispatches from the Twenty-Year War between a Television Reporter and His Medium, written in 1993, was a memoir of sorts. As an Emmy-winning correspondent for NBC News who later spent 10 years at Fox News before being fired, Burns knows the highs and lows of broadcasting. He’s since indicated that Fox is not a crucible of credibility, but rather “a cult.”

In 2006, he wrote his fourth book, Infamous Scribblers: The Founding Fathers and the Rowdy Beginnings of American Journalism, and his eighth, Invasion of the Mind Snatchers: Television’s Conquest of America in the Fifties, in 2010. Now, he’s publishing his 15th book, having tempered his tendency for unwieldly titles: 1957: The Year that Launched the American Future. Its bright red cover features the front of the Edsel, the Ford Motor Company’s catastrophe that Burns describes as “the car with the vagina in the grille.”

No question that 1957 was a big year. Russia won the space race with Sputnik, and President Eisenhower expanded the U.S. with the Interstate Highway Act, an idea he adopted from Germany after experiencing the ease and efficiency of the Autobahn. Highways give rise to suburbs, big cars, and a new way of life.

In 1957, Americans were introduced to the Mafia by watching the McClellan Rackets Committee hearings on television. TV also introduced Elvis the Pelvis, Little Richard, and the birth of rock ‘n’ roll, as well as Joe McCarthy, Fidel Castro, Jimmy Hoffa, Floyd Patterson, Billy Graham, and Ayn Rand. The hero of the 50s — hands down — was Dr. Jonas Salk, who developed the polio vaccine and refused to file a patent to profit from his discovery.

Burns divides his book into five parts, the most important being on race, the cutting issue of our times then and now. In 1957, the country was rocked by the Supreme Court decision known as Brown v. Board of Education, which stated that racial segregation in public schools violated the Fourteenth Amendment. “What happened next resulted in some of the most bitterly poignant tales to emerge…from the tenth circle of hell known as Southern racism.”

Burns recounts the trauma of nine African American students trying to enroll at Central High in Little Rock, Arkansas. Even decades later, it’s painful to read about white adults spitting race-laden epithets in the faces of the young Black students. Within a week of their enrollment, Congress voted on the Civil Rights Act of 1957, the first such piece of legislation to be approved since 1875, during the Southern revolts against Reconstruction.

But before the vote could be taken, South Carolina’s Strom Thurmond began filibustering on the floor of the U.S. Senate, raging against the legislation. He held the floor for 24 hours and 18 minutes, earning himself an ignoble place in the Guinness Book of Records for the longest filibuster in American history. Burns reports the incident in detail but fails to mention that the feral racist had a Black daughter, having impregnated his family’s 16-year-old maid when he was 22.

For those who have not discovered The Glory and the Dream: A Narrative History of America, 1932-1972 by William Manchester and just want a cursory gulp of 1957, Burns’ book will suffice; it offers more narrative than an almanac. But be prepared for sentences in need of a stop sign. In a chapter excoriating Ayn Rand, Burns writes:

“The kind of philosopher who so despises Rand, on the other hand, is usually an esoteric sort, like the fellow about whom I recently read who was watching a football game on television when it struck him that, in order to score, Team A has to cross Football Team B’s half of the field, thus sanctifying ‘the property-seizing principle’ of imperialism.”

And, when extolling the 1957 horror film “I Was a Teenage Werewolf,” he writes:

“Fowler goes on to say that the critics who condescended to review the film, invariably snickering at its simple-minded dialogue and plot devices, not to mention its almost comical special effects, had no idea what the movie was really about and rejected the concept of teenage angst as being just a laughable rite of passage, totally ignorant that the sort of angst that was swelling around them would birth a generation of intensely political angry and aware kids whose minds and hearts would affect the world.”

Burns goes on to say that the film became “the Edsel of motion pictures.” The same might be said of his book, minus the vagina.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Pride of Family

by Kitty Kelley

Carole Ione grew up in a world of beautiful Black women of various shades, where marriages crumbled, fathers fell by the wayside, and mothers forged ahead with careers and the “occasional” man. As a 10-year-old sitting at the piano listening to her mother sing Calypso songs, Ione, as she now calls herself, “learned early on from those lyrics that soldiers and sailors could be trouble — you might never see them again.”

Carole Ione grew up in a world of beautiful Black women of various shades, where marriages crumbled, fathers fell by the wayside, and mothers forged ahead with careers and the “occasional” man. As a 10-year-old sitting at the piano listening to her mother sing Calypso songs, Ione, as she now calls herself, “learned early on from those lyrics that soldiers and sailors could be trouble — you might never see them again.”

Ione’s only paladins were women: her great-aunt, Sistonie, a physician and member of Washington’s Black aristocracy; her grandmother, Be-Be, a former Broadway chorus dancer who ran the best restaurant in Saratoga Springs, drawing celebrities like Cab Calloway, Paul Robeson, Josephine Baker, and Ethel Waters; and her mother, Leighla, who carved a career writing mysteries. Ironically, the biggest mystery hid behind the stone wall of secrets that kept the women estranged and incapable of bonding as a family.

At the age of 19, against fierce objections, Ione married a white Frenchman. In 1956, they moved to his home in Alsace, where everyone in the textile-manufacturing town was white and spoke a German dialect called Elsässerditsch. That part of France, the Haut-Rhin, was scorned by Parisians as the exterieur, so its denizens tried to be “more French than the French,” Ione writes. As a Black American woman, she became a freakish curiosity, stared at in the streets:

“I realize now that it was exactly that depressing feeling of being thought inferior to the society I lived in that I had hoped to escape by marrying…[I longed] to assuage the painful and confusing aspects of blackness.”

Soon, she and her husband moved back to New York, where they occupied separate bedrooms and led separate lives as he encouraged a philosophy of free love. Ione began an affair with a married alcoholic man many years her junior, followed by an even more unconventional relationship with a woman painter who lived in a loft on Canal Street:

“I had begun to understand that I was — like most people, I thought — not simply heterosexual but sexual, and from then on I would resist any labels on my sexuality.”

After her divorce, she married “a gay man living as a heterosexual” with whom she had three children. But after 13 years “of no love for me,” she again divorced. Ione received no succor from her mother or grandmother, only a “frosty politeness.” Both blamed her for leaving her husband and becoming like them: a single mother.

Feeling betrayed and desperate for a sense of belonging, Ione sought to explore the lives of her family, a word she italicizes as if it’s exotic and foreign. The result, published in 1991 when she was 54, was Pride of Family: Four Generations of American Women of Color, a rich reverie of superb writing — half memoir, half biography — nine years in the making that probes the tortured bonds of mothers and daughters and the journey of one girl through a gnarled thicket of secrets.

With bracing honesty and eloquence, Ione documents in Pride of Family the alienation she felt within her own community, where a pernicious line of color had segregated her since childhood:

If you’re white, you’re all right.

If you’re brown, stick around.

If you’re black, get back.

When she found her maternal grandfather late in life, she asked him about his mother, and he said that she, Ione’s great-grandmother, was good-looking. “She was fair. Very light skin — and she had good hair.” That one word — hair — is freighted for Black women, and Ione was particularly sensitive about it as her mother and grandmother were light-skinned beauties with straight, silky hair:

“Mine was fuzzy, woolly, nappy…everything I didn’t want it to be…my hair was bad…not in the worst degrees of ‘bad’ — for there are degrees — but ‘bad’ nonetheless. Did this make my mother and grandmother love me less, did it create a subtle distance between us?”

That distance narrowed when Ione discovered the diary of her great-grandmother, Frances “Frank” Anne Rollin (1845-1902), and unearthed many family secrets. Rollin also gave Ione, a writer, a feeling of pride for her foremother, a 19th-century activist who was the first known African American biographer. In 1868, Rollin wrote The Life and Public Services of Martin R. Delany under the name Frank A. Rollin.

That biography is little known today, but the biographer lives on, having been recently embraced by Biographers International Organization (BIO), which established the Frances “Frank” Rollin Fellowship for African American Biography, providing a $2,000 fellowship for a writer working on a life story of an African American figure or someone whose story provides a significant contribution to the Black experience.

Ione, now 83 and living in Kingston, New York, is thrilled by the fellowship. “It’s a dream coming true through the centuries,” she told BIO. “There was a line in [Frank’s] diary in which she said she wanted to ‘make her mark in literature,’ and now [I feel] it’s finally happened.”

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

How to Lead

by Kitty Kelley

The Irish were the first to master the art of television conversation with The Late, Late Show, moderated by Gabe Byrne in Dublin from 1962-1990, and still running today with various hosts. Then came the British with David Frost, who hosted several U.K. “chat shows” before coming to America with The David Frost Show, and rising to international prominence in 1977 with his five 90-minute interviews with Richard Nixon, which forced the former president to acknowledge and apologize for Watergate. One of Frost’s many successors in London is Clive James, who currently hosts Talking in the Library.

The Irish were the first to master the art of television conversation with The Late, Late Show, moderated by Gabe Byrne in Dublin from 1962-1990, and still running today with various hosts. Then came the British with David Frost, who hosted several U.K. “chat shows” before coming to America with The David Frost Show, and rising to international prominence in 1977 with his five 90-minute interviews with Richard Nixon, which forced the former president to acknowledge and apologize for Watergate. One of Frost’s many successors in London is Clive James, who currently hosts Talking in the Library.

In the U.S., Larry King held sway on CNN every weeknight with Larry King Live! where he reigned for 25 years in colorful suspenders. He was followed by Charlie Rose, who invited guests to join him at his table on PBS from 1991 to 2017. When Rose was summarily fired for sexual harassment, he and his table were banished and replaced by two sturdy chairs for David M. Rubenstein to interview the great and the good on The David Rubenstein Show.

A co-founder of the Carlyle Group, a DC-based, multinational, private-equity investment firm, Rubenstein is a spectacular businessman worth $3.4 billion, and he’s capitalizing on his television show by publishing some of his interviews. His first book, The American Story: Conversations with Master Historians, published in 2019, was very good. His second, How to Lead: Wisdom from the World’s Greatest CEOs, Founders, and Game Changers, published last month, is okay.

The book’s cover features sketches of Oprah Winfrey, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Bill Gates, Christine Lagarde, Warren Buffett, Jeff Bezos, Indra Nooyi, Richard Branson, and Yo-Yo Ma. The contents present 30 individuals — 15 men and 15 women — Rubenstein deems as exemplifying leadership, whom he divides into different categories: visionaries, builders, transformers, commanders, decision-makers, and masters.

Half of Rubenstein’s leaders, mostly white males, hold degrees from Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Columbia, with a couple from Stanford. Not so the women, few of whom possess those prized credentials, with the exception of the late Justice Ginsburg.

In his introduction, Rubenstein presents his formula for becoming a world-class leader. Moses had 10 Commandments; Rubenstein has 12:

I. Luck.

II. Desire to succeed.

III. Pursue something new and unique.

IV. Hard work and long hours. (“Workaholism is a plus.”)

V. Focus everything on mastering one skill.

VI. Fail. (“My having been part of a failed White House certainly fueled my ambition to succeed,” he writes as former deputy domestic-policy assistant to President Carter.)

VII. Persistence.

VIII. Persuasion.

IX. Humble demeanor.

X. Credit-sharing. (Here, he quotes his hero, John F. Kennedy: “Victory has a hundred fathers, and defeat is an orphan.” So, spread the glory.)

XI. Ability to keep learning. (Rubenstein writes that he reads six newspapers a day, at least a dozen weekly periodicals, and a minimum of one book a week, although, he adds, he often juggles three to four books simultaneously. You wonder how the man finds time to tie his shoes.)

XII. Integrity, which he defines as not cutting ethical corners.

Rubenstein comes to all his interviews well prepared, if a bit short on charm. He’s developed a style much like Jack Webb on Dragnet: “Just the facts, Ma’am.” He’s respectful to his guests, even as his questions probe.

Interviewing Melinda Gates, he asks if it was difficult for her as a committed Catholic to promote birth control in third-world countries as part of her work with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. She admits she’d wrestled with her faith on the issue but finally resolved her conscience in favor of contraception.

How to Lead begins with the best interview in the book: Jeff Bezos, who happens to be the richest man in the world ($173.5 billion), founder and CEO of Amazon, and owner of the Washington Post. A high school valedictorian who graduated summa cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa from Princeton, Bezos changed his major from theoretical physics to electrical engineering and computer science when he realized he was not going to be one of the top 50 theoretical physicists in the world — an indication, perhaps, of why he prizes failure as a pathway to success.

(Here, Rubenstein admits his own financial failure, the biggest business mistake he made, selling his firm’s equity in Amazon for $80 million in 1996, which, today, would be worth “about $4 billion.”)

In his interview, Bezos reveals a man devoted to his parents. “One of the great gifts I got is my mom and dad,” he says. “I was always loved. My parents loved me unconditionally.” He adds that he’s committed to eight hours of sleep every night, and reserves “high IQ meetings” for mid-morning, when he has his best energy. He says the most important work he’s doing at present is investing in the future by putting $1 billion a year of his own money into Blue Origin, his aspirational program to make expanded human space travel a reality.

The only one of Rubenstein’s leaders without a college degree, let alone the advanced degrees that most of the others hold, is Richard Branson, a dyslexic who dropped out of school at 15. “Do you think you could have been more successful in life if you had a university degree?” Rubenstein asks. “No,” says Branson, who founded Virgin Group, an umbrella for hundreds of Virgin enterprises, including Virgin Airlines, Virgin Megastores, and Virgin Galactic. Branson is worth $4.2 billion.

Many of Rubenstein’s leaders are billionaires like himself, and with or without Ivy League credentials, all are accomplished and deserve their position at the top of the heap. For this book, Rubenstein includes his double interview with two former two-term presidents, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush.

But he has not interviewed his former boss, Jimmy Carter, a one-term president who many consider a leader in humanitarian outreach. Rubenstein characterizes Carter’s term in office as a “failed White House.” Yet Carter established the Department of Energy in 1977 and the Department of Education in 1979.

He cut the deficit, ended rampant inflation, and managed to get more of his legislation passed than any president since WWII, with the exception of Lyndon Johnson. And Carter, a Nobel laureate, is the only president since Thomas Jefferson under whom the U.S. military never fired a shot.

With all due respect to the billionaire Rubenstein, Carter’s presidency, while only four years, can hardly be dismissed as a failure.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Reaganland

by Kitty Kelley

Even in the digital age, there are some hardbacks that demand prominence on the bookshelf. Among them are the Bible; Webster’s New International Dictionary of the English Language (second edition, unabridged); Winston Churchill’s six-volume The Second World War; The Glory and the Dream: A Narrative History of America 1932-1972 by William Manchester; and Winnie-the-Pooh.

Even in the digital age, there are some hardbacks that demand prominence on the bookshelf. Among them are the Bible; Webster’s New International Dictionary of the English Language (second edition, unabridged); Winston Churchill’s six-volume The Second World War; The Glory and the Dream: A Narrative History of America 1932-1972 by William Manchester; and Winnie-the-Pooh.

Now, add Rick Perlstein’s four volumes documenting the rise of Conservatism in America. First, Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus; second, Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America; and third, The Invisible Bridge: The Fall of Nixon and the Rise of Reagan. Now comes the fourth and final installment, Reaganland: America’s Right Turn: 1976-1980, which covers the presidency of Jimmy Carter and his defeat by Ronald Reagan, and the New Right.

Perlstein has received critical acclaim for each volume, and rightly so. His latest tome, at more than 1,000 pages, deserves special praise because it capstones the political changes in 20th-century America that led to Ronald Reagan’s eight-year reign in the White House, plus the four years of George H.W. Bush’s presidency, which many Republicans refer to as “Reagan’s third term.”

Reaganland begins in July 1976, when the presidential landscape was Jimmy Carter vs. Jerry Ford, with Ronald Reagan, the sore loser, sitting on his hands, refusing to support Ford but claiming he did. The Gipper seemed too old to run again in 1980 at the age of 69, but Perlstein shows how he managed to become the Cinderella at the Conservative ball, aided by a beleaguered Carter, who never took him seriously, even when it was too late.

Not a news-making investigative foray into the Conservative movement, Reaganland is, instead, a phenomenal collection of data and detail masterfully woven into a compelling narrative about how the country turned right, steered brilliantly and cynically by think-tank founder Paul Weyrich and direct-mail mastermind Richard Viguerie.

Perlstein poured extraordinary research into this book, and those who lived through the era may be stunned to learn all they missed at the time — or wished they had. Some will remember such colorful characters as Marabel Morgan, the blonde with the bubble hairdo and pink lipstick, who wrote The Total Woman and, in concert with Phyllis Schlafly, helped to defeat the Equal Rights Amendment, along with the singer Anita Bryant, who campaigned ferociously against gays and gay rights. Others may recall “Battling Bella” Abzug and Betty Friedan, the latter of whom wrote The Feminine Mystique and spoke publicly about her aversion to lesbians, whom she called the “lavender menace.”

The year 1976 was called “the Year of the Evangelical” when Americans were introduced to the Christian Broadcasting Network; heard Debby Boone praise Jesus by singing “You Light Up My Life”; and met Tammy Faye and Jim Bakker, Pat Robertson, Jerry Falwell, Oral Roberts, Howard Phillips (known to evangelicals as a “completed Jew”), and Madalyn Murray O’Hair.

The crucial issues of the era included the Panama Canal treaties and the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) and SALT II; the Laffer Curve and “supply-side” economics; the fall of the shah, rise of the ayatollah, and taking of 52 American hostages in Iran (along with the eight lives lost trying to rescue them); Three Mile Island; the Camp David Accords; kidvid; and abortion, which Bill Moyers presented on television in 1978 as “the Issue that Will Not Go Away,” which, Perlstein writes, “was a pretty good bet.”

Pages later, the author describes a GOP fundraiser featuring “speakers from across the fruited plain” supping on “filet mignon and Jimmy Carter.” And quite a feast it was.

With editorial asides that are informed, trenchant, and occasionally laugh-out-loud funny, Perlstein pillories Democrats as much as he punches Republicans, and in the process becomes a trustworthy narrator. He makes a provocative case that the 1976 U.S. Senate election of Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) changed the legislative terrain and crushed labor-law reform, prompting one columnist to write: “Now is the time to put Big Labor up there with Santa Claus, the Easter Bunny and the Tooth Fairy.”

Writing with a light touch, Perlstein describes the dog whistles in Sen. Strom Thurmond’s newsletter to his constituents. The ardent segregationist from South Carolina praised “independent non-governmental schools” that support “prayers to God in school” and “regional ideals and values.” As Perlstein observes: “[H]e needn’t specify that the regional values he had in mind weren’t the consumption of fried green tomatoes.”

It’s stunning to read this book and realize the millions of dollars that have been spent trying to preserve white supremacy in the United States. Reagan’s racist strategy, after all, was to target “voters who felt victimized by government actions that cost them the privileges their whiteness once afforded them.”

Equally surprising is Perlstein’s declaration that Arthur Laffer, Robert A. Mundell, Robert Bartley, and Jude Wanniski were “arguably…the most influential economic thinkers in the history of the United States, even though their theories turned out to be substantially wrong.”

Unquestionably, Jimmy Carter’s presidency was hit with “crisis after crisis after crisis,” from Billygate to Bert Lance to a bitter challenge by Senator Ted Kennedy. But Carter seemed to create his own black cloud by preaching an austere gospel of gloom and doom, whereas Ronald Reagan blew bubbles about the economic boom he’d bring. “We live in the future in America, always have,” Reagan said. “And the better days are yet to come.”

Carter told hard truths; Reagan told soft lies. And, on November 4, 1980, the country voted for bubbles and better days.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Begin Again

By Kitty Kelley

Gird yourselves, white America: Eddie S. Glaude Jr. is putting you on notice, and he brought the receipts. The James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor of African American Studies at Princeton prefaces his eighth book with praise quotes from several platinum authors who laud his brilliance and the genius of his subject on display in Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own.

Gird yourselves, white America: Eddie S. Glaude Jr. is putting you on notice, and he brought the receipts. The James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor of African American Studies at Princeton prefaces his eighth book with praise quotes from several platinum authors who laud his brilliance and the genius of his subject on display in Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own.

To begin again on the subject of racism, Glaude proposes passing H.R. 40, a bill that would establish the Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African-Americans. It’s a suggestion that comes at the end of what the author himself describes in his introduction as “a strange book. It isn’t biography…it is not literary criticism…it is not straightforward history. Instead, Begin Again is some combination of all three in an effort to say something meaningful about our current times.”

Glaude starts gently but then lowers the boom. His book is a damning indictment of Donald Trump and white America, particularly white male America — or at least that part of it which believes in its superiority simply because it’s white.

Additionally, this book, provocative and lyrical in so many places, is Glaude’s personal journey through a tunnel of rage first explored by James Baldwin (1925-1987), whose writing — “close to seven thousand pages of work” — the professor has absorbed and studied and taught.

In Begin Again, Glaude challenges “the lie” that America is fundamentally good, that all men are created equal, and that the country is a beacon of light and a moral force in the world. “The stories we often tell ourselves of the civil rights movement and racial progress…[are] all too often lies,” he writes.

Instead, says the author, America is a racist nation that continues to tell the lie that it is a democracy while refusing to face the enduring legacy of slavery and ongoing systemic discrimination against African Americans.

With Baldwin as his guide, Glaude moves from the nonviolence practiced by Martin Luther King Jr. to the militancy of Huey P. Newton, Stokely Carmichael, and the Black Panther Party, the latter a “justifiable, even inevitable, response to white America’s betrayal of the civil rights movement.” Along the way, he lashes Richard Nixon’s “silent majority,” Reagan Democrats, and Trump voters for propagating “the lie.” Finally, Glaude concludes “that America is an identity that white people will protect at any cost.”

By 2016, he had become so disgusted by the Democratic Party for refusing to remedy Black suffering that he urged Black voters, many whose ancestors had paid with their lives for the right to vote, to abstain from voting for Hillary Clinton for president. His reasons seemed petty in the extreme:

“Much more was required than the Clinton name, or the endorsement of her bid for the presidency by President Obama, or by some celebrity, or the brandishing of hot sauce in [her] handbag.”

Choked by rage, he used his considerable influence to urge Black voters to leave the presidential ballot blank. Then the Republicans nominated Donald Trump. Still, Glaude refused to believe white America would elect “the carnival barker” to the highest office in the land.

Trimming his sails a bit, he co-authored an anemic essay in Time magazine with Fredrick Harris, a political scientist at Columbia, saying that if you were a Democrat in a battleground state like Wisconsin or Pennsylvania, you should vote for Hillary. But if you lived in a decidedly red state or an overwhelmingly blue one, you could blank out or vote your conscience.

Startlingly, the professor, who has studied Baldwin for 30 years, seems not to have learned from his mentor, especially on the value of presidential voting. In “Notes on the House of Bondage,” Baldwin ponders the 1980 presidential race between Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan:

“My vote will probably not get me a job or a home or help me through school or prevent another Vietnam or a third world war, but it may keep me here long enough for me to see, and use, the turning of the tide — for the tide has got to turn. And…if Carter is reelected, it will be by means of the black vote, and it will not be a vote for Carter. It will be a coldly calculated risk, a means of buying time.”

Surely, President Hillary Clinton would’ve bought Glaude more time than President Trump.

To his credit, Glaude admits his error. “I was wrong,” he writes, “and given my lifelong reading of Baldwin, it was an egregious mistake.”

Far less egregious, but still a mistake, was to publish this book without providing any photographs, especially since Glaude frequently refers to instances that demand illustration. For example, he writes about Sedat Pakay, a Turkish photographer who “offers a beautiful black-and-white portrait of Baldwin in the most intimate of settings.” No picture.

In another instance, Glaude refers to the opening of “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” a documentary of Baldwin’s time in the South during the Civil Rights movement, in which he sits “at a desk in his brother David’s apartment at 209 West Ninety-seventh Street, looking pensively at a book of photographs.” No picture. (Glaude writes pages about his own tour of the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, yet provides no pictures.)

He ends his book, appropriately, with a visit to Baldwin’s gravesite at Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, New York. Was it a simple marble stone, a granite slab, a large headstone marked with a quote? Or a family mausoleum to enfold Baldwin and his seven siblings? Sadly, there is again no picture. Glaude writes only that he knelt down, touched the earth, and quietly said, “Thank you.”

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books