Nancy Reagan

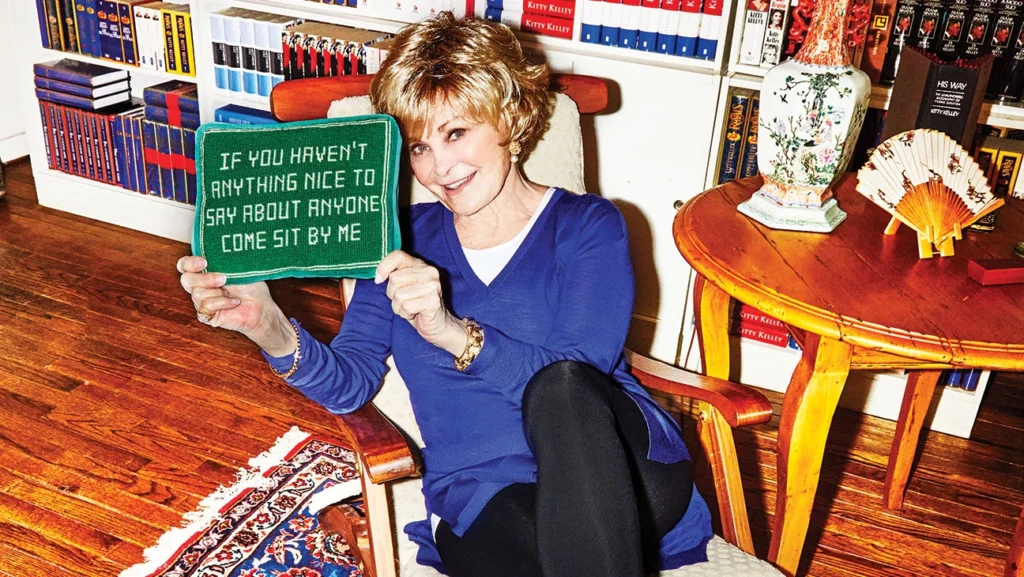

BIO Award Winner Kitty Kelley’s Speech

Kitty Kelley won the 2023 Biographers International Organization Award. On Saturday, May 20, at the 2023 BIO Conference, it was also announced that Kelley will make a gift of $1 million to BIO, to be given over the course of five years. You can read more about that here.

The following is Kitty’s keynote address:

If I get run over tonight, please make sure that this BIO award leads my obit, because it’ll be the only time that my name shares the same space with Ron Chernow and Robert Caro and Stacy Schiff. But I don’t want to think about obituaries right now. I want to share with you a little bit about the writing life that brings me here today.

I love books and as much as I enjoy fiction, I bend my knee to nonfiction, particularly biography—the art of telling a life story. All kinds of life stories—memoir, authorized and unauthorized biography, historical narrative, or contemporary profiles.

In the last few decades, I’ve written biographies about living icons, a genre that is sometimes dismissed as “unauthorized biography” and, unfortunately, the term is sometimes said as if you’re emptying a bedpan or cleaning up the dog’s mess. Unauthorized biographies are not approved by everyone and rarely appreciated by their subjects. One exception, of course, is the New Testament, which was written by disciples who never knew their subject.

About 40 years ago, I thought I’d died and gone to biography heaven when Bantam Books offered me a grand advance to write the unauthorized biography of Frank Sinatra. I’d written two previous biographies and been robbed on both. On the first one, I didn’t have an agent—which is like driving a car without a steering wheel. On the second, I had an agent straight out of Oliver Twist. You may remember the woman who advised Linda Tripp to advise Monica Lewinsky to save her blue dress. Well, that same woman was once a literary agent who caused about $70,000 in foreign sales to go missing on my Elizabeth Taylor biography. My lawyer was incensed and insisted I sue. I told him to write the agent, say I’d misplaced records, and ask for another accounting. I figured that way she could correct herself and repay the missing monies.

I’m embarrassed to admit that I let this go on for over a year because I just couldn’t believe a literary agent would steal from a client. My lawyer said, “Try to get it into your fat head: She’s not Max Perkins. She’s Ma Barker.”

After 17 months, I finally filed suit. Depositions were taken and the case went to federal court in Washington, D.C. I fully expected her to settle because the evidence was so overwhelming. Instead, the case went to trial and the jury found Ma Barker guilty on all six counts, including fraud. They demanded she make payment on the courthouse steps and even asked for punitive damages.

I suppose the lawsuit was a great victory, because I unloaded a bad agent and got a good one, but I was in no hurry to do another biography. I’d just learned the hard way that there’s no education in the second kick of a mule. I’d undertaken the Elizabeth Taylor biography, hoping to write about the Hollywood studio system that had shaped our fantasies for most of the 20th century. I envisioned weaving that theme into the life story of Elizabeth Taylor, who grew up as a little girl at MGM, and went to school at MGM and . . . married many MGM men. But my plan for this historical narrative soon got buried in Ms. Taylor’s Technicolor life of husbands and hospitals and jewelry stores.

My agent asked, if I were to consider writing another life story, who would be of interest? I said, “Well, the gold ring on the merry-go-round would be Frank Sinatra, because no one’s really done it, and he epitomizes the American dream.” She agreed and that was the end of the subject until a couple weeks later when she called and said she had a generous offer from Bantam Books.

Soon I was back in the biography business, thinking I’d paid my hard luck dues. I’d had a bandit publisher on my first book and a thieving agent on my second. Now was third time lucky. And for a few weeks it was . . . until I was served a subpoena from Frank Sinatra, announcing that he was suing me for $2 million dollars for usurping the rights to his life story. He claimed that he and he alone (or someone he authorized) was entitled to write his life story, and I certainly had not been authorized.

I immediately called my publisher, and Bantam’s legal counsel informed me that I was on my own. “Mr. Sinatra has not sued us,” she said. “He’s sued you, and since you’ve not given us a manuscript, we’re not involved. So, I’d advise you to get legal counsel in California, which is where you’ve been sued and do keep us informed.”

“But I haven’t written a word. I’ve only just begun. My manuscript is years away.”

“We’ll talk then,” she said, before hanging up.

Now, getting sued by a billionaire with Mafia ties concentrates the mind, especially after your publisher leaves the scene. I called my friend, the president of Washington Independent Writers, to commiserate. “I wish we could help you, Kitty, but we’re almost broke,” she said. I assured her that I wasn’t looking for money—just moral support. “Well, in that case, let me get on the horn.” She contacted several writers’ groups, including the Authors Guild and PEN and the American Society of Journalists and Authors, and Sigma Delta Chi, and the National Writers Union. Days later, they held a press conference at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., to denounce Sinatra for using his power and influence to intimidate a writer before she’d written a word. They denounced his lawsuit and his assault on the First Amendment. As journalists, they understood what was at stake if Sinatra prevailed.

I retained the law firm of O’Melveny and Myers in Los Angeles and tried to keep working on the book, but was interrupted a few weeks later when I was in New York doing interviews and my lawyer called to tell me to get back to D.C. because the LA lawyers were coming to Washington for a meeting that would also be attended by my publisher. The LA lawyers said they’d received a tape recording from Sinatra’s lawyers of me supposedly misrepresenting myself as Sinatra’s authorized biographer, and this tape recording was the proof that they were going to present in court.

Now I was scared, even though I knew I hadn’t made such a telephone call. But I began to second-guess myself, wondering if maybe under the pressure I’d snapped my cap. By the time the lawyers arrived that Monday morning I was ready for handcuffs.

Three teams of lawyers sat down in my living room and put the tape in the recorder. No one said a word for the first two minutes because what we heard sounded like Porky Pig flying high on helium. In a squeaky voice, Porky said he was me and Frank Sinatra told me to call for an interview. The lawyers played that tape three times and we all listened to Porky Pig again and again before anyone said a word. Then all the lawyers laughed, clearly relieved, knowing the tape was a phony. I didn’t laugh.

“This lawsuit has gone on for almost a year and now someone is willing to lie under oath to say that I misrepresented myself to get an interview.”

“Don’t worry. We’ll send this to the tape labs at U.S.C., they’ll send the report to Sinatra’s team, and we’ll file for a dismissal. Meantime, just tape all your interviews.”

I tried to explain to the lawyers that you couldn’t always tape interviews, especially in the early 1980’s, when the technology wasn’t sophisticated. Taping in restaurants was difficult over the clinking of glasses, and taping phone interviews wasn’t legal in every state, even with two-party permission.

I finally decided that the best way to protect myself was to write a thank-you note to everyone I interviewed. That turned out to be 800 notes. They were polite and also protective. I’d thank them for the time they gave me in their home or their office or their favorite bar—wherever we’d done the interview; I’d compliment them on the polka dot bow tie they wore or the pretty pink blouse or their red tennis shoes; I’d mention the fabulous décor, or a particular piece of art, or our great salad in such-and-such a restaurant—any detail that set the time or place. Then I’d send it off and keep a copy in my files, because three or four years later when the book was finally published, they might very well have forgotten that interview or, more likely, wish they had.

That happened with Frank Sinatra Jr. He’d agreed to be interviewed when he was performing in Washington, D.C. His representative asked if I’d be bringing a camera crew, and I said no crew, just a still photographer. Then I quickly called my friend Stanley Tretick, one of President Kennedy’s favorite photographers who had worked for UPI and then LOOK magazine.

Stanley and I arrived at the Capitol Hill Hilton in the afternoon and went to Sinatra’s suite. His publicist met us and then disappeared when Frank Jr. entered the room. Sinatra’s only son sat down and asked me to sit close to him because he didn’t want to strain his voice. He was performing that night. So, I moved over, notebook in hand. The first 30 minutes of the interview went well as Sinatra Jr. talked about accompanying his father on tour and hanging out in Vegas with his father’s friends. Then he leaned over and said, “Hon, I know what happened to Jimmy Hoffa.”

I didn’t move. Because no one knew what happened to Jimmy Hoffa. They knew he was dead, but they didn’t know how or by whom. And now the son of a mob-connected man was going to tell me.

For a split second I wondered what I should wear when I got the Pulitzer Prize.

Just as Frank Sinatra Jr. leaned over to whisper in my ear, Stanley dropped his camera bags on the floor, and said, “Well out with it, man. What the hell happened to Hoffa?”

Frank Sinatra Jr. reared back as if he’d been clubbed. He looked at me, then he bolted from his chair and ran into the bedroom, slamming the door. His publicist came running out and said we had to leave. I begged for more time, saying the interview wasn’t finished, but the publicist was physically pushing us out the door.

Up to that point, Stanley Tretick had been one of my closest friends. Now I looked at him as if he’d just been possessed by the Tasmanian devil.

“Aw, hell. He doesn’t know what happened to Jimmy Hoffa.”

“Really?” I said. “And since when are photographers clairvoyant? And what kind of a lunkhead photographer throws a hissy in the middle of a reporter’s interview? Did it ever occur to you that what the son of a mob-connected man has to say about the disappearance of Jimmy Hoffa might be of interest?”

By now I was down the steps and storming the street to hail a cab. I refused to ride in the same car with a crazy person when I was homicidal. I didn’t speak to Stanley for some time, but he became my best pal again when the Sinatra biography was published. By then Frank Sinatra had dropped his lawsuit but his son now decided to sue, denying he’d ever given me an interview. His lawyers contacted my publisher and everyone braced for another lawsuit. But Stanley produced one of the photos he’d taken during our interview that showed me sitting next to Frank Sinatra Jr. with a notebook in [my] hand and a tape recorder on the table.

That photograph certainly trumped all of my little thank-you notes. Yet I can’t tell you how many times those notes saved me. When I wrote the Nancy Reagan biography, letters rained down on Simon & Schuster from corporate tycoons and all manner of political operatives, who took offense with the words attributed to them or to their wives or secretaries or associates, and at the bottom of every letter was a “cc” to President Ronald Reagan. Each time the publisher’s lawyer would call me to go over my notes and my tapes, and then he’d send a courteous reply, saying the publisher stands by the book and its accuracy.

At first, I wanted the publisher to “cc: President Reagan” just like all the letter writers had done, but the lawyer said no reason to stir the beast. “Those are weasel letters. They’re sent simply to show the flag.” He was right, and there were no retractions and no lawsuits.

That controversial biography became the cover of Time, Newsweek, People, Entertainment Weekly, and The Columbia Journalism Review, and [was] presented on the front pages of The New York Times, The New York Post, and the New York Daily News.

On the day of publication, President and Mrs. Reagan held a press conference to denounce the book, saying that I had—quote—“clearly exceeded the bounds of decency.” And three days later, President Richard Nixon agreed. President Nixon wrote a letter to President Reagan to commiserate. President Reagan responded, saying that everyone he knew had denied talking to the author. Reagan even named the minister of his church, who’d been cited as a source, and the minister had written a denial to all his parishioners in the Bel Air Presbyterian Church bulletin.

Now, I really tried not to respond to every accusation, but this one from a man of the cloth got to me, and I wrote to remind him of the 45 minute interview he’d given in his office. I enclosed a transcript of his taped remarks and asked him to please send around another church bulletin—with a correction. Of course, he didn’t, which proves the wisdom of Winston Churchill, who said that a lie flies halfway around the world before the truth gets its pants on.

Having rankled President Reagan and President Nixon, I later rattled President George Herbert Walker Bush. I’d written to him as a matter of courtesy, when I was under contract to Doubleday to write a historical retrospective of the Bush family, and said I’d appreciate an interview sometime at his convenience.

President Bush never responded to me but he directed his aide to write my publisher, saying:

“President Bush has asked me to say that he and his family are not going to cooperate with this book because the author wrote a book about Nancy Reagan that made Mrs. Reagan unhappy.” First Lady Barbara Bush had been so incensed when she saw my books displayed in the First Ladies Exhibit at the Smithsonian that she directed the curator to remove the display, which he did the next day. In fact, I might not have known about it had I not taken my niece to the Smithsonian a few weeks before and we’d seen the display and took a picture of it.

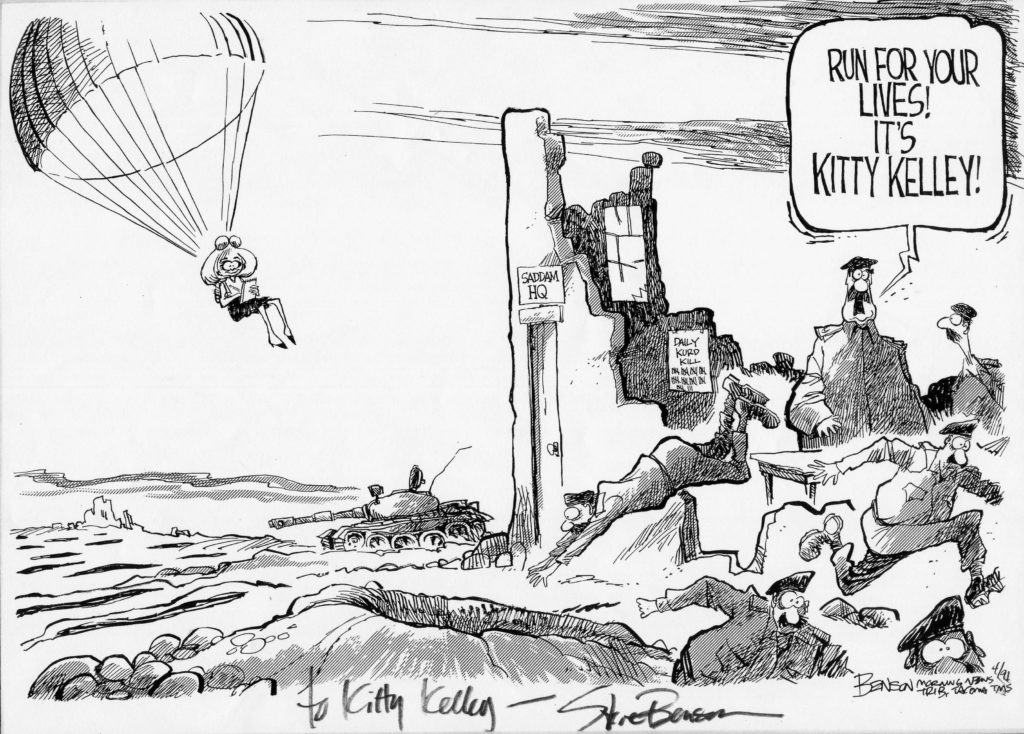

That photograph now hangs in my guest bathroom next to autographed cartoons from Jules Feiffer and Garry Trudeau. Over the years, that loo has become crowded with cartoons from all of my various books. My sister was very impressed when she saw them. She said to my husband, “I think it’s great that Kitty has put up all the bad ones.” My husband said, “There were no good ones.”

My biography on the Bush family dynasty was published in 2004, in the midst of a contentious presidential campaign. Bush Jr. was running for a second term, and I was lambasted by his White House press secretary, the White House deputy press secretary, the White House communications director, the Republican National Committee, and the house majority leader, Tom DeLay. Mr. DeLay even wrote a colorful letter to my publisher, saying that I was—quote—“in the advanced stage of a pathological career” and the publisher was in—quote—“moral collapse for publishing such a scandalous enterprise.”

When the Bush book became number one on the New York Times bestseller list, I was dropped from the masthead of The Washingtonian Magazine, where I’d been a contributing editor for 30 years. The new owner of the magazine was a Bush presidential appointee. The editor told me, “Your book was too personal. Too revealing.”

“But that’s what a biography is,” I said. “It’s an intimate examination of a person in his times, and in this case a powerful person in the public arena. The President of the United States influences our society, with actions that affect our lives.”

I quoted the actor Melvyn Douglas from the movie Hud. He talked about the mesmerizing power of a public image: “Little by little the look of the country changes because of the men we admire.” And Colum McCann, in his novel Let the Great World Spin, wrote: “Repeated lies become history, but they don’t necessarily become the truth.”

This is why biography is so vital to a healthy society. Whether authorized or unauthorized, biography presents a life story—sometimes it’s an x-ray of a manufactured image, sometimes it’s a gauzy bandage. The best biographers try to penetrate dross and drill for gold. As President Kennedy said, “The great enemy of the truth is very often not the lie—deliberate, contrived and dishonest—but the myth, persistent, persuasive, and unrealistic.”

I do not relish living in a world where information is authorized, sanitized, and homogenized. I read banned books. I applaud whistleblowers and I reject any suppression by church or state. To me, the unauthorized biography, which requires a combination of scholarly research and investigative reporting, is best directed at those figures still alive and able to defend themselves, who exercise power over our lives. . . . I firmly believe that unauthorized biography can be a public service and a boon to history.

The most solid support I’ve received over the years has come from writers—journalists and historians and biographers—who believe in the First Amendment. Who champion the public’s right to know.

These are principles that feed my soul and fill my heart, which is why I’m so grateful to be honored by you today with this award.

Thank you.

Kitty Kelley Wins 2023 BIO Award

Kitty Kelley has won the 14th BIO Award, bestowed annually by the Biographers International Organization to a distinguished colleague who has made major contributions to the advancement of the art and craft of biography.

Widely regarded as the foremost expert and author of unauthorized biography, Kelley has displayed courage and deftness in writing unvarnished accounts of some of the most powerful figures in politics, media, and popular culture. Of her art and craft, Kelley said, in American Scholar, “I do not relish living in a world where information is authorized, sanitized, and homogenized. I read banned books, I applaud whistleblowers, and I reject any suppression by church or state. To me, the unauthorized biography, which requires a combination of scholarly research and investigative reporting, is best directed at those figures still alive and able to defend themselves, who exercise power over our lives. . . . I firmly believe that unauthorized biography can be a public service and a boon to history.”

Among other awards, Kelley was the recipient of: the 2005 PEN Oakland/Gary Webb Anti-Censorship Award; the 2014 Founders’ Award for Career Achievement, given by the American Society of Journalists and Authors; and, in 2016, a Lifetime Achievement Award, given by The Washington Independent Review of Books. Her impressive list of lectures and presentations includes: leading a winning debate team in 1993, at the University of Oxford, under the premise “This House Believes That Men Are Still More Equal Than Women;” and, in 1998, a lecture at the Harvard Kennedy School for Government on the subject “Public Figures: Are Their Private Lives Fair Game for the Press?” In addition, Kelley was named by Vanity Fair to its Hall of Fame as part of the “Media Decade” and she has been a New York Times bestseller multiple times.

For over 30 years, Kelley has been a full-time freelance writer. In addition to the American Scholar, her writing has appeared in The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, Newsweek, Ladies’ Home Journal, The Chicago Tribune, The Washington Times, The New Republic, and McCall’s. She is also a frequent contributor to The Washington Independent Review of Books.

Heather Clark, chair of the BIO Awards Committee, said: “The Awards committee is thrilled to recognize Kitty Kelley for her outstanding contributions to biography over nearly six decades. We admire her courage in speaking truth to power, and her determination to forge ahead with the story in the face of opposition from the powerful figures she holds accountable. The committee would also like to recognize Kitty’s many years of service to BIO, especially her fundraising prowess and commitment to growing BIO’s membership ranks. Kitty is a force of nature and a deeply inspiring figure who deserves the highest recognition from BIO for her contributions to advancing the art and craft of biography.”

Of her award, Kelley said, “I’m dazzled by the BIO honor and feel like Cinderella when the glass slipper fit. Please don’t wake me up from this dream.”

Previous BIO Award winners are Megan Marshall, David Levering Lewis, Hermione Lee, James McGrath Morris, Richard Holmes, Candice Millard, Claire Tomalin, Taylor Branch, Stacy Schiff, Ron Chernow, Arnold Rampersad, Robert Caro, and Jean Strouse.

Kelley will give the keynote address at the 2023 BIO Conference, on Saturday, May 20.

2023 BIO Award Winner Kitty Kelley interviewed by Heath Hardage Lee, March 28, 2023

Queen of the Unauthorized Biography Spills Her Own Secrets

By Seth Abramovitch

There was, not that long ago, a name whose mere invocation could strike terror in the hearts of the most powerful figures in politics and entertainment.

That name was Kitty Kelley.

If it’s unfamiliar to you, ask your mother, who likely is in possession of one or more of Kelley’s best-selling biographies — exhaustive tomes that peer unflinchingly (and, many have claimed, nonfactually) into the personal lives of the most famous people on the planet.

“I’m afraid I’ve earned it,” sighs Kelley, 79, of her reputation as the undisputed Queen of the Unauthorized Biography. “And I wave the banner. I do. ‘Unauthorized’ does not mean untrue. It just means I went ahead without your permission.”

That she did. Jackie Onassis, Frank Sinatra, Nancy Reagan — the more sacred the cow, the more eager Kelley was to lead them to slaughter. In doing so, she amassed a list of enemies that would make a despot blush. As Milton Berle once cracked at a Friars Club roast, “Kitty Kelley wanted to be here tonight, but an hour ago she tried to start her car.”

Only a handful of contemporary authors have achieved the kind of brand recognition that Kelley has. At the height of her powers in the early 1990s, mentions of the ruthless journo with the cutesy name would pop up everywhere from late night monologues to the funny pages. (Fully capable of laughing at herself, her bathroom walls are covered in framed cartoons drawn at her expense.)

Kelley is hard to miss around Washington, D.C. She drives a fire-engine red Mercedes with vanity plates that read “MEOW.” The car was a gift from former Simon & Schuster chief Dick Snyder, who was determined to land Kelley’s Nancy Reagan biography.

“Simon & Schuster said, ‘Kitty, Dick really wants the book. What will it take to prove that?’ ” she recalls. “I said,  ‘A 560 SL Mercedes, bright red, Palomino interior.’ ‘We’ll be back to you.’ ” She insists she was only kidding. But a few days later, Kelley answered the phone and was directed to walk to the nearest corner: “Your bright red 560 SL is sitting there waiting for you.” Sure enough, there it was. The “MEOW” plates were a surprise gift from the boyfriend who would become her second husband, Dr. John Zucker.

‘A 560 SL Mercedes, bright red, Palomino interior.’ ‘We’ll be back to you.’ ” She insists she was only kidding. But a few days later, Kelley answered the phone and was directed to walk to the nearest corner: “Your bright red 560 SL is sitting there waiting for you.” Sure enough, there it was. The “MEOW” plates were a surprise gift from the boyfriend who would become her second husband, Dr. John Zucker.

Ask Kelley how many books she has sold, and she claims not to know the exact number. It is many, many millions. Her biggest sellers — 1986’s His Way, about Frank Sinatra, and 1991’s Nancy Reagan: The Unauthorized Biography, began with printings of a million each, which promptly sold out. “But they’ve gone to 12th printings, 14th printings,” she says. “I really couldn’t tell you how many I’ve sold in total.” She does recall first breaking into The New York Times‘ best-seller charts, with 1978’s Jackie Oh! “I remember the thrill of it. I remember how happy I was. It’s like being prom queen,” she says. “Which I actually was about 100 years ago.”

Regardless of one’s opinions about Kelley, or her methodology, there can be no denying that her brand of take-no-prisoners celebrity journalism — the kind that in 2022 bubbles up constantly in social media feeds in the form of TMZ headlines and gossipy tweets — was very much ahead of its time.

In fact, a detail from Kelley’s 1991 Nancy Reagan biography trended in December when Abby Shapiro, sister of conservative commentator Ben Shapiro, tweeted side-by-side photos of Madonna and the former first lady. “This is Madonna at 63. This is Nancy Reagan at 64. Trashy living vs. Classic living. Which version of yourself do you want to be?” read the caption. Someone replied with an excerpt from Kelley’s biography that described Reagan as being “renowned in Hollywood for performing oral sex” and “very popular on the MGM lot.” The excerpt went viral and launched a wave of memes. “It doesn’t fit with the public image. Does it? It just doesn’t. And the source on that was Peter Lawford,” says Kelley, clearly tickled that the detail had resurfaced.

While amplifying those kinds of rumors might not suggest it, in many eyes, Kelley is something of a glass-ceiling shatterer. “Back when she started in the 1970s, it was a largely male profession,” says Diane Kiesel, a friend of Kelley’s who is a judge on the New York Supreme Court. “She was a trailblazer. There weren’t women writing the kind of hard-hitting books she was writing. I’m sure most of her sources were men.”

But what of her methodology? Kelley insists she never sets out to write unauthorized biographies. Since Jackie Oh!, she has always begun her research by asking her subjects to participate, often multiple times. She is invariably turned down, then continues about the task anyway. She’s also known to lean toward blind sourcing and rely on notes, plus tapes and photographs, to back up the hundreds of interviews that go into every book.

“Recorders are so small today, but back then it was very hard to carry a clunky tape recorder around and slap it on the table in a restaurant and not have all of that ambient noise,” she says. To prove the conversations happened, Kelley devised a system in which she would type up a thank-you note containing the key details of their meeting — location, date and time — and mail it to every subject, keeping a copy for herself. If a subject ever denied having met with her, she would produce the notes from their conversation and her copy of the thank-you note.

So far, the system has worked. While many have tried to take her down, the ever-grinning Kelley has never been successfully sued by a source or subject.

Now 79, she lives in the same Georgetown townhouse she purchased with her $1.5 million advance (that’s $4 million adjusted for inflation) for His Way, which the crooner unsuccessfully sued to prevent from even being written.

Among the skeletons dug up by Kelley in that 600-page opus: that Ol’ Blue Eyes’ mother was known around  Hoboken, New Jersey, as “Hatpin Dolly” for a profitable side hustle performing illegal abortions. Sinatra’s daughter Nancy Sinatra said the family “strangled on our pain and anger” over the book’s release, while her sister, Tina, said it caused her father so much stress, it forced him to undergo a seven-and-a-half-hour surgical procedure on his colon.

Hoboken, New Jersey, as “Hatpin Dolly” for a profitable side hustle performing illegal abortions. Sinatra’s daughter Nancy Sinatra said the family “strangled on our pain and anger” over the book’s release, while her sister, Tina, said it caused her father so much stress, it forced him to undergo a seven-and-a-half-hour surgical procedure on his colon.

Giggly, vivacious and 5-foot-3, Kelley presents more like a kindly neighbor bearing blueberry muffins than the most infamous poison-pen author of the 20th century. “I seem to be doing more book reviewing than book writing these days,” she says in one of our first correspondences and points me to a review of a John Lewis biography published in the Washington Independent Review of Books.

She has not tackled a major work since 2010’s Oprah — a biography of Oprah Winfrey touted ahead of its release by The New Yorker as “one of those King Kong vs. Godzilla events in celebrity culture” but which fizzled in the marketplace, barely moving 300,000 copies. Among its allegations: that Winfrey had an affair early in her career with John Tesh — of Entertainment Tonight fame — and that, according to a cousin, the talk show host exaggerated tales of childhood poverty because “the truth is boring.”

“We had a falling out because I didn’t want to publish the Oprah book,” says Stephen Rubin, a consulting publisher at Simon & Schuster who grew close to Kelley while working with her at Doubleday on 2004’s The Family: The Real Story of the Bush Dynasty.

“I told her that audience doesn’t want to read a negative book about Saint Oprah. I don’t think it’s something she should have even undertaken. We have chosen to disagree about that.”

The book ended up at Crown. It would be nine months before Kelley would speak to Rubin again. They’ve since reconciled. “She’s no fun when she’s pissed,” Rubin notes.

Adds Kelley of Winfrey’s reaction to the book: “She wasn’t happy with it. Nobody’s happy with [an unauthorized] biography. She was especially outraged about her father’s interview.” She is referencing a conversation she had, on the record, with Winfrey’s father, Vernon Winfrey, in which he confirmed the birth of her son, who arrived prematurely and died shortly after birth.

But Kelley says the backlash to Oprah: A Biography and the book’s underwhelming sales had nothing to do with why she hasn’t undertaken a biography since. Rather, her husband, a famed allergist in the D.C. area who’d give a daily pollen report on television and radio, died suddenly in 2011 of a heart attack. “John was the great love of her life,” says Rubin. “He was an irresistible guy — smart, good-looking, funny and mad for Kitty.”

“Boy, I was knocked on my heels,” she says of Zucker’s death. “He hated the cold weather. He insisted we go out to the California desert. We were in the desert, and he died at the pool suddenly. I can’t account for a couple of years after that. It was a body blow. I just haven’t tackled another biography since.”

A decade having passed, Kelley does not rule out writing another one — she just hasn’t yet found a subject worthy of her time. “I can’t think of anyone right now who I would give three or four years of my life to,” Kelley says. “It’s like a college education.”

For fun, I throw out a name: Donald Trump. Kelley shakes her head vigorously. “I started each book with real respect for each of my subjects,” she says. “And not just for who they were but for what they had accomplished and the imprint that they had left on society. I can’t say the same thing about Donald Trump. I would not want to wrap myself in a negative project for four years.”

“You know,” I interrupt, “I’m imagining people reading that quote and saying, ‘Well, you took ostensibly positive topics and turned them into negative topics.’ How would you respond to that?”

“I would say you’re wrong,” Kelley replies. “That’s what I would say. I think if you pick up, I don’t know — the Frank Sinatra book, Jackie Oh!, the Bush book — yes, you’re going to see the negatives and the positives, which we all have. But I think you’ll come out liking them. I mean, we don’t expect perfection in the people around us, but we seem to demand it in our stars. And yet, they’re hardly paragons. Each book that I’ve written was a challenge. But I would think that if you read the book, you’re going to come out — no matter what they say about the author — you’re going to come out liking the subject.”

***

Kelley arrived in the nation’s capital in 1964. She was 22 and, through the connections of her dad, a powerful attorney from Spokane, Washington, she landed an assistant job in Democratic Sen. Eugene McCarthy’s office. She worked there for four years, culminating in McCarthy’s 1968 presidential bid. It was a tumultuous time. McCarthy’s Democratic rival, Robert F. Kennedy, was gunned down in Los Angeles at a California primary victory party on June 5. When Hubert Humphrey clinched the nomination that August amid the DNC riots in Chicago, Kelley’s dreams of a future in a McCarthy White House were dashed, and she decided a life in politics was not for her.

“But I remain political,” Kelley clarifies. “I am committed to politics and have been ever since I worked for Gene McCarthy. I was against the war in Vietnam. I don’t come from that world. I come from a rich, right-wing Republican family. My siblings avoid talking politics with me.”

In 1970, she applied for a researcher opening in the op-ed section at The Washington Post. “It was a wonderful job,” she recalls. “I’d go into editorial page conferences. And whatever the writers would be writing, I would try and get research for them. Ben Bradlee’s office was right next to the editorial page offices. And if he had both doors open, I would walk across his office. He was always yelling at me for doing it.”

According to her own unauthorized biography — 1991’s Poison Pen, by George Carpozi Jr. — Kelley was fired for taking too many notes in those meetings, raising red flags for Bradlee, who suspected she might be researching a book about the paper’s publisher, Katharine Graham. Kelley says the story is not true.

“I have not heard that theory, but I will tell you I loved Katharine Graham, and when I left the Post, she gave me a gift. She dressed beautifully, and when the style went from mini to maxi skirts —because she was tall and I am not, I remember saying, ‘Mrs. Graham, you’re going to have to go to maxis now. And who’s going to get your minis?’ She laughed. It was very impudent. But then I was handed a great big box with four fabulous outfits in them — her miniskirts.”

Kelley says she left the Post after two years to pursue writing books and freelancing. She scored one of the bigger scoops of 1974 when the youngest member of the upper house — newly elected Democratic Sen. Joe Biden of Delaware, then 31 — agreed to be profiled for Washingtonian, a new Beltway magazine.

Biden was still very much in mourning for his wife and young daughter, killed by a hay truck while on their way to buy a Christmas tree in Delaware on Dec. 18, 1972. The future president’s two young sons, Beau and Hunter, survived the wreck; Biden was sworn into the Senate at their hospital bedsides.

After the accident, Biden developed an almost antagonistic relationship to the press. But his team eventually softened him to the idea of speaking to the media. That was precisely when Kelley made her ask.

Biden would come to deeply regret the decision. The piece, “Death and the All-American Boy,” published on June 1, 1974, was a mix of flattery (Kelley writes that Biden “reeks of decency” and “looks like Robert Redford’s Great Gatsby”), controversy (she references a joke told by Biden with “an antisemitic punchline”) and, at least in Biden’s eyes, more than a little bad taste.

The piece opens: “Joseph Robinette Biden, the 31-year-old Democrat from Delaware, is the youngest man in the Senate, which makes him a celebrity of sorts. But there’s something else that makes him good copy: Shortly after his election in November 1972 his wife Neilia and infant daughter were killed in a car accident.”

Later, Kelley writes, “His Senate suite looks like a shrine. A large photograph of Neilia’s tombstone hangs in the inner office; her pictures cover every wall. A framed copy of Milton’s sonnet ‘On His Deceased Wife’ stands next to a print of Byron’s ‘She Walks in Beauty.’ “

But it was one of Biden’s own quotes that most incensed the future president.

She writes: ” ‘Let me show you my favorite picture of her,’ he says, holding up a snapshot of Neilia in a bikini. ‘She had the best body of any woman I ever saw. She looks better than a Playboy bunny, doesn’t she?’ “

“I stand by everything in the piece,” says Kelley. “I’m sorry he was so upset. And it’s ironic, too, because I’m one of his biggest supporters. It was 48 years ago. I would hope we’ve both grown. Maybe he expected me to edit out [the line about the bikini], but it was not off the record.” Still, she admits her editor, Jack Limpert, went too far with the headline: “I had nothing to do with that. I was stunned by the headline. ‘Death and the All-American Boy.’ Seriously?”

It would be 15 years before Biden gave another interview, this time to the Washington Post‘s Lois Romano during his first presidential bid, in 1987. Biden, by then remarried to Jill Biden, recalled to Romano, “[Kelley] sat there and cried at my desk. I found myself consoling her, saying, ‘Don’t worry. It’s OK. I’m doing fine.’ I was such a sucker.”

Kelley’s first book wasn’t a biography at all. “It was a book on fat farms,” she says, which was based on a popular article she’d written for Washington Star News on San Diego’s Golden Door — one of the country’s first luxury spas catering to celebrity clientele like Natalie Wood, Elizabeth Taylor and Zsa Zsa Gabor.

“On about the third day, the chef came out, and he said, ‘Would you like a little something?’ ” says Kelley. “He was Italian. I said, ‘Yes, I’m so hungry.’ And he kind of laughed. Turns out he wasn’t talking about tuna fish. I said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me.’ He said, ‘I have sex all the time with the people here.’ I said, ‘I should tell you, I’m here writing a book.’ He said, ‘I’ll tell you everything!’ I warned him, ‘OK — but I’m going to use names.’ And I did.”

The book, a 1975 paperback called The Glamour Spas, sold “14 copies, all of them bought by my mother,” she says. But the publisher, Lyle Stuart, dubbed in a 1969 New York Times profile as the “bad boy of publishing,” was impressed enough with Kelley’s writing that he hired her in 1976 to write a biography of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

The crown jewel of the book that would become Jackie Oh! was Kelley’s interview with Sen. George Smathers, a Florida Democrat and John F. Kennedy’s confidant. (After they entered Congress the same year and quickly became close friends, Kennedy asked Smathers to deliver two significant speeches: at his 1953 wedding and his 1960 DNC nomination.)

“It was quite explosive,” Kelley recalls of her three-hour dinner with Smathers. “He was very charming, very Southern and funny. And he said, ‘Oh, Jack, he just loved women.’ And he went on talking, and he said, ‘He’d get on top of them, just like a rooster with a hen.’ I said, ‘Senator, I’m sorry, but how would you know that unless you were in the room?’ He said, ‘Well, of course I was in the room. Jack loved doing it in front of people.’

“The senator, to his everlasting credit, did not deny it,” Kelley continues. “A reporter asked him, ‘Did you really say those things?’ And the senator replied, ‘Yeah, I did. I think I was just run over by a dumb-looking blonde.’ “

She followed that one, which landed on the New York Times best-seller list, with 1981’s Elizabeth Taylor: The Last Star, which underwhelmed. Her next two, however — His Way and Nancy Reagan: The Unauthorized Biography (for which she earned a $3.5 million advance, $9 million in 2022 adjusted for inflation) — were best-sellers, moving more than 1 million copies each in hardcover.

She followed that one, which landed on the New York Times best-seller list, with 1981’s Elizabeth Taylor: The Last Star, which underwhelmed. Her next two, however — His Way and Nancy Reagan: The Unauthorized Biography (for which she earned a $3.5 million advance, $9 million in 2022 adjusted for inflation) — were best-sellers, moving more than 1 million copies each in hardcover.

Her 1997 royal family exposé, The Royals — which presaged The Crown, the Lady Di renaissance and Megxit mania by several decades — contained allegations that the British royal family had obfuscated their German ancestry.

“Sinatra was huge and Nancy was huge, but The Royals gave me more foreign sales than I’ve ever had on any book,” Kelley beams, adding that the recent headlines about Prince Andrew settling with a woman who accused him of raping her as a teenager at Jeffrey Epstein’s compound “really shows the rotten underbelly of the monarchy, in that someone would be so indulged, really ruined as a person, without much purpose in life.”

“Looking around,” I ask Kelley, “is society in decline?”

“What a question,” she replies. “Let’s say it’s being stressed on all sides. I think it’s become hard to find people that we can look up to — those you can turn to to find your better self. We used to do that with movie stars. People do it with monarchy. Unfortunately, there are people like Kitty Kelley around who will take us behind the curtain.”

Contrary to her public persona, Kelley is known in D.C. social circles for her gentility. Judge Kiesel, a part-time author, first met her eight years ago when Kelley hosted a reception for members of the Biographers International Organization at her home.

“What amazed me was she was such the epitome of Southern hospitality, even though she isn’t from the South,” says Kiesel. “I remember her standing on the front porch of her beautiful home in Georgetown and personally greeting every member of this group who had showed up. There had to be close to 200 of us.”

Kelley hosts regular dinner parties of six to 10 people. “She likes to mix people from publishing, politics and the law,” says Kiesel. When Kiesel, who lives in New York City, needed to spend more time in D.C. caring for a sister diagnosed with cancer, Kelley insisted she stay at her home. “She threw a little dinner party in my honor,” Kiesel recalls. “I said, ‘Kitty — why are you doing this?’ She said, ‘You’re going to have a really rough couple of months and I wanted to show you that I’m going to be there for you.’ People look at her as this tough-as-nails, no-holds-barred writer — but she’s a very kind, sweet, generous woman.”

For Kelley, life has grown pretty quiet the past few years: “It’s such a solitary life as a writer. The pandemic has turned life into a monastery.” Asked whether she dates, she lets out a high-pitched chortle. “Yes,” she says. “When asked. No one serious right now. Hope springs eternal!”

I ask her if there is anything she’s written she wishes she could take back. “Do I stand by everything I wrote? Yes. I do. Because I’ve been lawyered to the gills. I’ve had to produce tapes, letters, photographs,” she says, then adds, “But I do regret it if it really brought pain.”

Says Rubin: “People think she’s a bottom-feeder kind of writer, and that’s totally wrong. She’s a scrupulous journalist who writes no-holds-barred books. They’re brilliantly reported.”

Before I bid her adieu, I can’t resist throwing out one more potential subject for a future Kelley page-turner.

“What about Jeff Bezos?” I say.

She pauses to consider, and you can practically hear the gears revving up again.

“I think he’s quite admirable,” she says. “First of all, he saved The Washington Post. God love him for that. And he took on someone who threatened to blackmail him. He stood up to it. I think there’s much to admire and respect in Jeff Bezos. He sounds like he comes from the most supportive parents in the world. You don’t always find that with people who are so successful.”

“So,” I say. “You think you have another one in you?”

“I hope so,” Kelley says. “I know you’re going to end this article by saying … ‘Look out!’ “

This story first appeared in the March 2 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine.

https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/lifestyle/arts/kitty-kelley-interview-unauthorized-biographies-1235101933/

Photo credits: top of page, Amy Lombard; Kitty Kelley in Merc, Amy Lombard; Kitty Kelly with His Way, Bettmann/Getty Images; Kitty Kelley with Elizabeth Taylor: The Last Star, Harry Hamburg/NY Daily News Archive/Getty Images

Reaganland

by Kitty Kelley

Even in the digital age, there are some hardbacks that demand prominence on the bookshelf. Among them are the Bible; Webster’s New International Dictionary of the English Language (second edition, unabridged); Winston Churchill’s six-volume The Second World War; The Glory and the Dream: A Narrative History of America 1932-1972 by William Manchester; and Winnie-the-Pooh.

Even in the digital age, there are some hardbacks that demand prominence on the bookshelf. Among them are the Bible; Webster’s New International Dictionary of the English Language (second edition, unabridged); Winston Churchill’s six-volume The Second World War; The Glory and the Dream: A Narrative History of America 1932-1972 by William Manchester; and Winnie-the-Pooh.

Now, add Rick Perlstein’s four volumes documenting the rise of Conservatism in America. First, Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus; second, Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America; and third, The Invisible Bridge: The Fall of Nixon and the Rise of Reagan. Now comes the fourth and final installment, Reaganland: America’s Right Turn: 1976-1980, which covers the presidency of Jimmy Carter and his defeat by Ronald Reagan, and the New Right.

Perlstein has received critical acclaim for each volume, and rightly so. His latest tome, at more than 1,000 pages, deserves special praise because it capstones the political changes in 20th-century America that led to Ronald Reagan’s eight-year reign in the White House, plus the four years of George H.W. Bush’s presidency, which many Republicans refer to as “Reagan’s third term.”

Reaganland begins in July 1976, when the presidential landscape was Jimmy Carter vs. Jerry Ford, with Ronald Reagan, the sore loser, sitting on his hands, refusing to support Ford but claiming he did. The Gipper seemed too old to run again in 1980 at the age of 69, but Perlstein shows how he managed to become the Cinderella at the Conservative ball, aided by a beleaguered Carter, who never took him seriously, even when it was too late.

Not a news-making investigative foray into the Conservative movement, Reaganland is, instead, a phenomenal collection of data and detail masterfully woven into a compelling narrative about how the country turned right, steered brilliantly and cynically by think-tank founder Paul Weyrich and direct-mail mastermind Richard Viguerie.

Perlstein poured extraordinary research into this book, and those who lived through the era may be stunned to learn all they missed at the time — or wished they had. Some will remember such colorful characters as Marabel Morgan, the blonde with the bubble hairdo and pink lipstick, who wrote The Total Woman and, in concert with Phyllis Schlafly, helped to defeat the Equal Rights Amendment, along with the singer Anita Bryant, who campaigned ferociously against gays and gay rights. Others may recall “Battling Bella” Abzug and Betty Friedan, the latter of whom wrote The Feminine Mystique and spoke publicly about her aversion to lesbians, whom she called the “lavender menace.”

The year 1976 was called “the Year of the Evangelical” when Americans were introduced to the Christian Broadcasting Network; heard Debby Boone praise Jesus by singing “You Light Up My Life”; and met Tammy Faye and Jim Bakker, Pat Robertson, Jerry Falwell, Oral Roberts, Howard Phillips (known to evangelicals as a “completed Jew”), and Madalyn Murray O’Hair.

The crucial issues of the era included the Panama Canal treaties and the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) and SALT II; the Laffer Curve and “supply-side” economics; the fall of the shah, rise of the ayatollah, and taking of 52 American hostages in Iran (along with the eight lives lost trying to rescue them); Three Mile Island; the Camp David Accords; kidvid; and abortion, which Bill Moyers presented on television in 1978 as “the Issue that Will Not Go Away,” which, Perlstein writes, “was a pretty good bet.”

Pages later, the author describes a GOP fundraiser featuring “speakers from across the fruited plain” supping on “filet mignon and Jimmy Carter.” And quite a feast it was.

With editorial asides that are informed, trenchant, and occasionally laugh-out-loud funny, Perlstein pillories Democrats as much as he punches Republicans, and in the process becomes a trustworthy narrator. He makes a provocative case that the 1976 U.S. Senate election of Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) changed the legislative terrain and crushed labor-law reform, prompting one columnist to write: “Now is the time to put Big Labor up there with Santa Claus, the Easter Bunny and the Tooth Fairy.”

Writing with a light touch, Perlstein describes the dog whistles in Sen. Strom Thurmond’s newsletter to his constituents. The ardent segregationist from South Carolina praised “independent non-governmental schools” that support “prayers to God in school” and “regional ideals and values.” As Perlstein observes: “[H]e needn’t specify that the regional values he had in mind weren’t the consumption of fried green tomatoes.”

It’s stunning to read this book and realize the millions of dollars that have been spent trying to preserve white supremacy in the United States. Reagan’s racist strategy, after all, was to target “voters who felt victimized by government actions that cost them the privileges their whiteness once afforded them.”

Equally surprising is Perlstein’s declaration that Arthur Laffer, Robert A. Mundell, Robert Bartley, and Jude Wanniski were “arguably…the most influential economic thinkers in the history of the United States, even though their theories turned out to be substantially wrong.”

Unquestionably, Jimmy Carter’s presidency was hit with “crisis after crisis after crisis,” from Billygate to Bert Lance to a bitter challenge by Senator Ted Kennedy. But Carter seemed to create his own black cloud by preaching an austere gospel of gloom and doom, whereas Ronald Reagan blew bubbles about the economic boom he’d bring. “We live in the future in America, always have,” Reagan said. “And the better days are yet to come.”

Carter told hard truths; Reagan told soft lies. And, on November 4, 1980, the country voted for bubbles and better days.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

BIO Podcast

Kitty Kelley spoke with BIO member John A. Farrell in February 2020 in Washington, D.C.

Kitty Kelley spoke with BIO member John A. Farrell in February 2020 in Washington, D.C.

Part I (26:53):

Part II (26:26):

John A. Farrell’s website: http://www.jafarrell.com/

Biographers International Organization: https://biographersinternational.org/

BIO Podcasts: https://biographersinternational.org/podcasts/

Part I URL:

https://biographersinternational.org/news/podcast/podcast-episode-45-kitty-kelley-part-i/?fbclid=IwAR0N2CMGj5Fzg5bY4Rx1VsXkGCd2HHri1K0jOKHbgf8x4uJlIwGliZWGlFI

Part II URL:

https://biographersinternational.org/news/podcast/podcast-episode-46-kitty-kelley-part-ii/?fbclid=IwAR1xJI97oOu5YbQSP2_4M6dl1DABV7g12Wnzcjp2MpdbU4fr5tHY3683kOg

BIO Board of Directors

- Linda Leavell, President (2019-2021)

- Sarah S. Kilborne, Vice President (2020-2022)

- Marc Leepson, Treasurer (2019-2021)

- Billy Tooma, Secretary (2020-2022)

- Kai Bird (2019-2021)

- Deirdre David (2019-2021)

- Natalie Dykstra (2020-2022)

- Carla Kaplan (2020-2022)

- Kitty Kelley (2019-2021)

- Heath Lee (2019-2021)

- Steve Paul (2020-2022)

- Anne Boyd Rioux (2019-2021)

- Marlene Trestman (2019-2021)

- Eric K. Washington (2020-2022)

- Sonja Williams (2019-2021)

The American Story

by Kitty Kelley

For those who love history and enjoy biography, David M. Rubenstein has delivered a masterstroke with The American Story, in which he presents his interviews with authors of notable biographies. Among them are David McCullough on John Adams; Ron Chernow on Alexander Hamilton; Taylor Branch on Martin Luther King Jr.; Walter Isaacson on Benjamin Franklin; Robert Caro on Lyndon Johnson; and Doris Kearns Goodwin on Abraham Lincoln.

For those who love history and enjoy biography, David M. Rubenstein has delivered a masterstroke with The American Story, in which he presents his interviews with authors of notable biographies. Among them are David McCullough on John Adams; Ron Chernow on Alexander Hamilton; Taylor Branch on Martin Luther King Jr.; Walter Isaacson on Benjamin Franklin; Robert Caro on Lyndon Johnson; and Doris Kearns Goodwin on Abraham Lincoln.

In total, The American Story is a delectable smorgasbord of U.S. history, covering 39 books discussed by 15 authors, some of whom have written more than one biography.

The American Story grew from an idea Rubenstein proposed in 2013 to present a dinner series for members of Congress entitled “Congressional Dialogues,” in which he would interview acclaimed historians in the gilded setting of the Library of Congress.

He said his purpose was to educate public servants, “to provide the members with more information about the great leaders and events in our country’s past, with the hope that, in exercising their various responsibilities, our senators and representatives would be more knowledgeable about history and what it can teach us about future challenges.”

He also hoped that bringing the members together in a nonpartisan setting might reduce the rancor in Washington. Six years later, he admits the jury is out on the former and that absolutely no traction has been gained on the latter.

Rubenstein, who made his fortune ($3.6 billion) in private equity as co-founder of the Carlyle Group, styles himself as a “patriotic philanthropist,” having purchased the last privately owned original Magna Carta for $21.3 million and then loaning it to the National Archives.

In addition, he has given $7.5 million to repair the Washington Monument; $13.5 million to the National Archives for a new gallery; $20 million to the Thomas Jefferson Foundation; and $10 million to Montpelier to renovate James Madison’s home. So, when the “patriotic philanthropist” asked to host his own interviews at the Library of Congress, the answer was, quite sensibly, yes.

Yet Rubenstein brings more than his b-for-boy-billions to this book. He has delved deeply into American history, having read at least one biography of each president and “every single biography” about John F. Kennedy, the commander-in-chief with whom he feels the greatest connection.

He has donated millions to the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston, the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard, and the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, DC, where he serves as chairman of the board of trustees. He recently contributed $50 million for the Kennedy Center’s REACH expansion, upon which his name is chiseled in marble.

As much as Rubenstein admires our 35th president, however, his interview with biographer Richard Reeves (President Kennedy: Profile of Power) shows some of the dark side of JFK’s reign, including the assassination of Rafael Trujillo, the dictator of the Dominican Republic, and the attempted assassination of Fidel Castro.

Some readers will be startled to learn that JFK knew in advance about the Berlin Wall (“for which he was practically a co-contractor,” says Reeves) and had, in effect, consented to building it to protect the small U.S. force of 15,000 soldiers in West Germany from the hundreds of thousands of Russian soldiers on the eastern side.

The American Story shows almost every president to have had a flaw that scarred his legacy: FDR turned away Jewish refugees, sending them back to sure death under Hitler; JFK misfired on the Bay of Pigs; Richard Nixon resigned over Watergate; Vietnam doomed Lyndon Johnson; and, with the exception of John Adams, all the Founding Fathers owned slaves. Yet, as Walter Isaacson put it so well, “The Founders were the best team ever fielded.”

In mining nuggets of history, Jean Edward Smith (Eisenhower in War and Peace) reveals that D-Day might have failed had Hitler not been sleeping. His best Panzer tank troops were available to repel the invading Allies, but only he could give the order to use them, and no one dared wake the Führer during the initial hours of the landing. By the time he woke up, the Normandy beachheads had been secured.

Did the Allies know Hitler had orders not to be disturbed while sleeping? Or was it a matter of the great good luck that Smith said accompanied Eisenhower throughout his life?

Early in his career, Ike was almost court-martialed for claiming his son on his housing allowance for $250 (valued at $3,000 in 2017) even though his son was not living with him. Gen. John J. Pershing got the charge reduced to a letter of reprimand, and Eisenhower soared to a glorious career as a five-star general.

The Q&A format of this book is ingenious. Rubenstein, who’s mastered his subject matter, asks informed questions that stimulate impressive responses, and the “patriotic philanthropist” is not above probing into the personal and provocative:

About Benjamin Franklin: “He seemed to have a lot of girl friends.”

About Alexander Hamilton: “He had a bit of an amorous reputation. In fact, what did Martha Washington call her tomcat?”

About Dwight Eisenhower: “He was the only [WWII] general who may have had [an affair with] his ‘driver.’ Is that right?”

About Ronald Reagan: “Did he dye his hair?”

Rubenstein’s most engaging interview, with U.S. Supreme Court chief justice John G. Roberts Jr., comes at the end of the book. Roberts studied history as an undergrad at Harvard with hopes to make it his career, but then changed his mind.

“I was driving back to school from Logan Airport in Boston one day and I talked to the cabdriver. I said, ‘I’m a history major at Harvard.’ And he said, ‘I was a history major at Harvard…’ [After that] I thought I would move to law.”

Rubenstein, also a lawyer, responds: “In the first year of law school — really in the first month or two — you realize certain people have the ability to quickly do legal reasoning. They have the knack of it, and some people don’t. You must have realized that it wasn’t as hard as you had thought it would be.”

Smart as Rubenstein is, you have to love Roberts, who graduated cum laude from Harvard Law School: “It was as hard as I thought it would be. It was pretty hard throughout.”

The American Story is a creative concept that delivers delicious bite-size bits of American history to those who haven’t had the time or inclination to read widely. I devoured every page with immense pleasure.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

What It’s Like to Be Kitty Kelley

Originally published in Washingtonian October 2019

I’ve been in DC since, let’s see . . . since Abraham Lincoln was President! I came to help with Senator Eugene McCarthy’s Foreign Relations Committee mail for a six-week stint, but I ended up in his Senate office and stayed four years. I remember that his personal secretary, who looked like she had been on the job 102 years, took one look at me and said, ‘Can she type or take shorthand?’ McCarthy replied, ‘We don’t ask the impossible of anyone around here.’ I thought, This guy has got a great sense of humor.

When I left the Hill in 1968, I became the researcher for the Washington Post editorial page. After two fabulous years at the paper, I got a book contract to investigate the beauty-spa industry. Since I weighed three pounds less than a horse, I signed fast and saddled up to visit every fat farm in the country. I got myself down to pony size, and the book probably sold 14 copies—all to my mother.

Then I backed into writing biographies, beginning with Jackie Oh! I love the genre, but writing an unauthorized biography brings its challenges. The subjects I’ve chosen are extremely powerful public figures who’ve had a vast impact on our lives and are fully invested in their images. Consequently, the blowback can be considerable.

I remember when my Nancy Reagan book came out in 1991, my late husband, John, who was courting me at the time, took me to Bice, then a real hot spot in DC. As we walked in, a man stood up and started yelling, ‘Booooo! Get that bitch out of here! Boo! Boo!’ John turned around to see who the guy was yelling at. I knew and looked straight ahead, praying not to cry. The man kept yelling, everyone turned to look, and then a woman on the other side of the restaurant started yelling, ‘No, no—she’s brave!’ The two of them went at each other, and the restaurant suddenly looked like tennis at Wimbledon, turning from one side to the other. The maître d’ brought us to a table, and John buried himself in the wine list. Then a guy from the middle of the room threw his napkin on the floor and headed for our table. I thought for sure we were goners. He spread out his arms and embraced me: ‘Kitty, you don’t know me, but I’m going to stand here until this stops.’ It was Tony Coehlo, the majority whip in the House of Representatives. I introduced him to John, who said, ‘Congressman, you go in the will.’ John told me later he was going to propose over dinner but was so flummoxed by what happened, he put it off for 24 hours.

My Bush-family book drew fire from the White House, the Republican National Committee, and the GOP leader in the House of Representatives. I framed all the cartoons and hung them where they belong—in the loo. My favorite is the bubble-headed blonde in Chanel shoes parachuting into Saddam Hussein’s bunker, scattering the armed guards, who yell, ‘Run for your lives! It’s Kitty Kelley!’

I don’t write about just anybody. I only choose huge figures who have manufactured a public image. I’m fascinated to find out what they’re really like. I’m not doing another great big bio simply because, at this moment in time, I don’t want to know what anyone out there is really like. Certainly not Trump. Melania? Oh, definitely not.

I’ve already done seven New York Times bestsellers. I can’t say that I loved doing them, but I sure loved finishing them.

The Watergate: Inside America’s Most Infamous Address

by Kitty Kelley

Hotels can intrigue, even captivate. In the pantheon of places, nothing tantalizes so much as a good story situated in a hotel, particularly a luxury hotel with hot- and cold-running bellhops, genuflecting valets, and chandeliers that drip with crystal. (Think the Metropol in A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles.)

Hotels can intrigue, even captivate. In the pantheon of places, nothing tantalizes so much as a good story situated in a hotel, particularly a luxury hotel with hot- and cold-running bellhops, genuflecting valets, and chandeliers that drip with crystal. (Think the Metropol in A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles.)

Built on superstition, few hotels have a 13th floor — most elevators go from 12 to 14 — but each floor can hold secrets, whether dreadful or delightful. As such, hotels have been the subject of movies (“Grand Hotel” with Greta Garbo; “The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel” with Judi Dench); novels (Hotel Du Lac by Anita Brookner); children’s books (Eloise at the Plaza by Kay Thompson); a rollicking BBC television series (“The Duchess of Duke Street,” the story of the king’s mistress, who owned the Cavendish Hotel in London); and even an Elvis Presley classic (“Heartbreak Hotel”).

Hotel sites beguile, possibly because they provide escapes from the real world and adventures for the escapees, which translates into vicarious pleasure for the rest of us.

Whether fact or fiction, the standard recipe for a good hotel story contains basic ingredients:

1 lb. Scandal

1 c. Sex

2 c. Eccentric guests

1 dash Crime

1 pinch Skullduggery

For added spice, mix in two cups of chopped celebrity and bake for 350 pages. Voila. You’ve got the perfect hotel-story soufflé.

Joseph Rodota followed this recipe to write his first book, The Watergate: Inside America’s Most Infamous Address. For scandal, crime, and skullduggery, he provides the 1972 burglary of the Democratic National Committee, which led to the resignation of President Richard Nixon, which, in turn, spawned a great film, “All the President’s Men.”

For eccentricity, Rodota showcases Martha Mitchell, wife of Nixon’s attorney general, and her midnight phone calls. Freshly sprung from a psychiatric ward in New York to move to Washington with her husband after Nixon’s inauguration, Martha soon gave hilarious definition to drinking and dialing. Belting back bourbon late at night, she frequently called Helen Thomas, UPI’s White House correspondent, to unload on “Mr. President.”

For eccentric good measure and a smidge of sex, Rodota also tosses in the Chinese hostess (cue Anna Chennault) who served “concubine chicken” at her Watergate dinner parties.

From John F. Kennedy to John Mitchell to the johns who paid for prostitutes, this book drops more names than a prison roll call. With the exception of Monica Lewinsky, who lived in her mother’s Watergate apartment in the 1990s, where she hung the blue dress that led to the impeachment of President Bill Clinton, most of the dropped names are Nixon-era Republicans (Senators Elizabeth and Bob Dole), Rosemary Woods, and cabinet members like Maurice Stans, John Volpe, and Emil “Bus” Mosbacher.

With skillful research from old newspapers and magazines, oral histories from presidential libraries, and a few interviews, Rodota has fashioned an interesting story about the white concrete edifice that looks like a giant clamshell. With three buildings of wrap-around co-op apartments terraced with egg-carton balustrades, the Watergate, facing the Potomac River, sits adjacent to the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.

To tell his story from the beginning, Rodota burrows into the complicated bureaucracy that surrounds any major construction in the nation’s capital. He whacks through the weeds of proposals and counter-proposals from the financiers, architects, and developers to the National Capital Planning Commission, the DC Zoning Commission, the National Park Service, the Commission on Fine Arts, the committee overseeing the National Cultural Center (later to be named the Kennedy Center), the U.S. Congress, and, finally, the White House. All had to reach agreement before a shovel broke ground.

Beginning in 1962, numerous hearings were held to discuss plans for Watergate Towne, a complex that would include a gourmet restaurant, spa, beauty salon, grocery store, liquor store, cleaners, florist, bakery, and a boutique of designer clothes for women. Still, there was concern, especially over the project’s financing and what the Kennedy White House called “the Catholic problem.”

As the first Catholic to be elected president — and only by 100,000 votes — John F. Kennedy knew his religion was problematic to many. As president, he genuinely wanted to make Washington “a more beautiful and functional city,” which the Watergate project promised to do. But he would not sign off on the $50 million proposal because it was largely underwritten by the Vatican, then the principal shareholder in the developing company Società Generale Immobiliare.

The formidable columnist Drew Pearson stoked controversy over “popism” with a syndicated column headlined: “Vatican Seeks Imposing Edifice on Potomac.” A group called Protestants and Other Americans United for Separation of Church and State mobilized its members.

Within weeks, the White House received more than 3,000 letters opposing construction of the Watergate and, according to one, “having Miami Beach come to Washington.” Most voiced outrage that Kennedy would be under clerical pressure to do the bidding of “the world’s richest church.” The Vatican soon divested its interest in the project, and, by November 22, 1963, most objections were muted.

Probably because there is no breaking news in Rodota’s book, his publisher sent a letter to editors and producers trying to burnish the fact that “The Vatican, the coal miners of Britain, and Ronald Reagan have something in common: They each owned a piece of the Watergate. Ronald Reagan held a financial stake in the Watergate complex shortly before becoming president, a fact that has never been made public before this book.”

Wowza! Stop the presses!

Yet the author does a good job of mixing historical facts with personal anecdotes to tell the story of what was both the most famous and most infamous hotel in Washington, DC, until the presidential election of 2016. Perhaps Rodota will follow this book with another hotel story entitled Tales from the Trump International, which might indeed provide some needed wowza.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

The Vanity Fair Diaries: 1983-1992

by Kitty Kelley

The British excel as diarists, the most famous being Samuel Pepys, followed by James Boswell (the biographer of Dr. Johnson), and Virginia Woolf, the beacon of the Bloomsbury Group. Currently, Alan Bennett, 83, reigns supreme.

The British excel as diarists, the most famous being Samuel Pepys, followed by James Boswell (the biographer of Dr. Johnson), and Virginia Woolf, the beacon of the Bloomsbury Group. Currently, Alan Bennett, 83, reigns supreme.

Now comes Tina Brown pawing at that pedestal with The Vanity Fair Diaries: 1983-1992, which chronicles her glory days as the English editor who came to America to revive the magazine, and later to resuscitate the New Yorker. For this she deserves heaps of Yankee praise.

Once I got my mitts on her book, I did what everyone will do: I turned to the index. Back in 1989, I was lucky enough to be selected along with Ted Turner, Diane Sawyer, Steven Spielberg, and others (plus the tombstone of Andy Warhol) as part of “the Media Decade” in Vanity Fair’s Hall of Fame. Each of us was photographed by Annie Leibovitz, who signed and sent originals of the shots as Christmas presents. I was curious to see if the diaries mentioned that 40-page spread in the magazine.

Flipping to the back of the book, I see one entry on page 347 about “the biggest media influencers” of the era. Wowza. There I am. Whoops. “Trashy Biographer Kitty Kelley.” But I’m not alone. Similar smackdowns await others.

Brown zings Jerry Zipkin, “always in high malice mode” as “Nancy Reagan’s viperish portly walker.” She cuffs Charlotte Curtis, the New York Times editor, as “unbearable,” adding, “What a bogus grandee she is, a coiffed asparagus, exuding second-rate intellectualism.”

She bashes Oscar de la Renta as a “conniving bastard,” but after a kiss-and-make-up lunch, she sees “a nicer side of Oscar at last.” Arnold Scaasi is “the dreaded frock miester,” and Richard Holbrooke “an egregious social climber.”

After inviting Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis to a dinner party in honor of Clark Clifford, Brown dings the former First Lady (“Jackie Yo!”) as “crazed,” writing: “I felt if you left her alone, she’d be in front of a mirror, screaming.” Then she zaps Onassis for “understated malice” in not “writing me a thank you note.”

Midway through these diaries, you might think that most of Brown’s roadkill has been gathered up and gone to the angels. Given the passage of time, some attrition among the grandees of Gecko greed is understandable, but one wonders if Brown would’ve disparaged Si Newhouse, her billionaire benefactor at Conde Nast, as “a hamster,” an insecure “gerbil” frequently in “chipmunk mode,” if he were still alive. Safely dead, he gets blasted for having “no balls at all” because he caved to Nancy Reagan’s request to see Vanity Fair’s profile of her and the president before publication.

Read on, though, and you’ll see that Brown’s slingshot takes equal aim at those not yet consigned to the cemetery. Kurt Vonnegut’s photographer wife, Jill Krementz, is zapped for “extreme pushiness”; Henry Kissinger “is a rumbling old Machiavelli”; Peter Duchin “name drop[s] at deafening volume”; Robert Gottlieb, Brown’s predecessor at the New Yorker, is “a preposterous snob”; and Clint Eastwood is an excruciating bore.

“How could one be bored after one course with the world’s biggest heartthrob?” she asks. “I was.”

She cuffs her former friend Sally Quinn for disinviting her to Ben Bradlee’s birthday party because of Vanity Fair’s book review by Christopher Buckley, who characterized Quinn’s first novel as “cliterature.” Sally was “wild with fury,” Brown writes, a bit puzzled that “the sharpshooter journalist,” who had once libeled Zbigniew Brzezinski, would be so sensitive.

(In a profile for the Washington Post, Quinn wrote that Brzezinski, then national security advisor to President Carter, had unzipped his fly during an interview with a female reporter from People, which Quinn claimed had been captured by a photographer. The next day, the Washington Post retracted her false story: “Brzezinski did not commit such an act, and there is no picture of him doing so.”)

Brown does not chop with a cleaver. She wields her scalpel with surgical precision, blood-letting with small, incisive cuts. She doesn’t linger over the corpse, either. In fact, in these diaries, she jumps from mourning the death of a friend one day to tra-la-la-ing the next as she sits with Vogue’s Anna Wintour, drawing up guest lists for yet another dinner party.

Brown makes intriguing entries about New York’s new-money barons, particularly Donald Trump, who keeps a collection of Hitler’s speeches in his office. On February 23, 1990, she writes that Trump, in between wife number one and two, is “having a fling with a well-known New York socialite. If true, this could give Trump what money can’t buy — the silver edge of class.”

Alas, she doesn’t reveal the name of the silver belle, but she does relate that Trump, enraged by Marie Brenner’s 1988 takedown of him in Vanity Fair, sneaks behind her at a black-tie gala and pours a glass of wine down her back.

One marvels at Brown’s indefatigable energy as she sprints from breakfast with Barry Diller to lunch with Norman Mailer to dinner with the Kissingers. Every day, every night: the parties, the premieres, the galas, the spas, the stylists, the hairdressers, the designers, the limousines. Even she admits exhaustion at her frantic drive to see and be seen — all in service to her role as editor, of course.

These diaries are a celebrity drive-by of the great and the good and, sprinkled with high and low culture, are written with style but little humor, save for the night the newly arrived London editor attended her first Manhattan cocktail party and met Shirley MacLaine.

“What do you do?” Brown asked the movie star. This is laugh-out-loud funny, except to someone who’s laughed in many previous lives. MacLaine was not amused. Upon meeting Lana Turner when the MGM siren was 62, Brown, then 29, decides to “get a piece done that uses her [Turner] as a prism for all the glamorous stars who age without pity.”

The British writer Graham Boynton, who applauds Brown’s high-octane journalism, wrote affectionately in the Telegraph about her early days editing Vanity Fair. Reading a submitted draft for the Christmas issue, she scribbled, “Beef it up, Singer.” Boynton recalled, “It had to be tactfully explained to her that Isaac Bashevis Singer was a Nobel Prize winner for literature.”

I’m knocked out by these diaries, marveling that they were written at the time in such perfect prose. Do all her sentences fall to the page like rose petals in a summer breeze? No editing? No rewriting? No tweaking? If so, this “trashy biographer” genuflects. (My own diaries read like the daily romps of an unhinged mind scrambling for cruise control.)

Diaries provide a psychological X-ray of the diarist, an unintentional autobiography of sorts, and these entries show a woman of immense talent consumed with her dazzling career. And as tough as she is (and must be) in a man’s world, her feminist self resents being dismissed.

When Ad Age demeans her as a “starlet wanting to play Juliet,” she punches back. It’s “fucking sexist crap,” she writes. “Women get stuck with being trivialized and just have to smile.”

Flicking off such criticism like a fuzzball from cashmere, Tina Brown smiles all the way to the bank and then rockets upward, leaving the rest of us in her high-heeled wake

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Vanity Fair December 1989

The 1989 Hall of Fame – The Media Decade

Star Sleuth Kitty Kelley

“Catty Kitty stalked the four great beasts of the celebrity jungle—Jackie, Nancy, Liz and Frank. Doing it her way, she clawed past hostile flacks and stonewalling cronies….”

The President Will See You Now

by Kitty Kelley

I picked up The President Will See You Now, a memoir by Peggy Grande of her 10 years with Ronald Reagan after he left the White House in 1989, with misgivings. Since that time, more than 500 biographies and staff memoirs of Reagan have been published, in addition to his own autobiography and 15 volumes of his Presidential Papers.

I picked up The President Will See You Now, a memoir by Peggy Grande of her 10 years with Ronald Reagan after he left the White House in 1989, with misgivings. Since that time, more than 500 biographies and staff memoirs of Reagan have been published, in addition to his own autobiography and 15 volumes of his Presidential Papers.

There is also the Ronald Reagan Legacy Project, which works to place a monument or memorial to the former president in every state, and, to date, has established Reagan landmarks in 38 of them. The next stated goal is to place a public building named after Reagan in the 3,140 counties in the U.S., proving, if nothing else, a continuing commitment to the Gipper.

At one time, I, too, was fascinated by all things Reagan and researched the subject thoroughly to write Nancy Reagan: The Unauthorized Biography, a 1991 book featured on the covers of Time and Newsweek. Some people, particularly the Reagans, who held a press conference to denounce the book, felt it was too critical of the former first lady, although I gave her full marks for making possible all of her husband’s stunning success.