Stanley Tretick

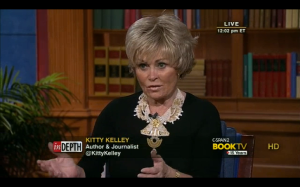

BIO Award Winner Kitty Kelley’s Speech

Kitty Kelley won the 2023 Biographers International Organization Award. On Saturday, May 20, at the 2023 BIO Conference, it was also announced that Kelley will make a gift of $1 million to BIO, to be given over the course of five years. You can read more about that here.

The following is Kitty’s keynote address:

If I get run over tonight, please make sure that this BIO award leads my obit, because it’ll be the only time that my name shares the same space with Ron Chernow and Robert Caro and Stacy Schiff. But I don’t want to think about obituaries right now. I want to share with you a little bit about the writing life that brings me here today.

I love books and as much as I enjoy fiction, I bend my knee to nonfiction, particularly biography—the art of telling a life story. All kinds of life stories—memoir, authorized and unauthorized biography, historical narrative, or contemporary profiles.

In the last few decades, I’ve written biographies about living icons, a genre that is sometimes dismissed as “unauthorized biography” and, unfortunately, the term is sometimes said as if you’re emptying a bedpan or cleaning up the dog’s mess. Unauthorized biographies are not approved by everyone and rarely appreciated by their subjects. One exception, of course, is the New Testament, which was written by disciples who never knew their subject.

About 40 years ago, I thought I’d died and gone to biography heaven when Bantam Books offered me a grand advance to write the unauthorized biography of Frank Sinatra. I’d written two previous biographies and been robbed on both. On the first one, I didn’t have an agent—which is like driving a car without a steering wheel. On the second, I had an agent straight out of Oliver Twist. You may remember the woman who advised Linda Tripp to advise Monica Lewinsky to save her blue dress. Well, that same woman was once a literary agent who caused about $70,000 in foreign sales to go missing on my Elizabeth Taylor biography. My lawyer was incensed and insisted I sue. I told him to write the agent, say I’d misplaced records, and ask for another accounting. I figured that way she could correct herself and repay the missing monies.

I’m embarrassed to admit that I let this go on for over a year because I just couldn’t believe a literary agent would steal from a client. My lawyer said, “Try to get it into your fat head: She’s not Max Perkins. She’s Ma Barker.”

After 17 months, I finally filed suit. Depositions were taken and the case went to federal court in Washington, D.C. I fully expected her to settle because the evidence was so overwhelming. Instead, the case went to trial and the jury found Ma Barker guilty on all six counts, including fraud. They demanded she make payment on the courthouse steps and even asked for punitive damages.

I suppose the lawsuit was a great victory, because I unloaded a bad agent and got a good one, but I was in no hurry to do another biography. I’d just learned the hard way that there’s no education in the second kick of a mule. I’d undertaken the Elizabeth Taylor biography, hoping to write about the Hollywood studio system that had shaped our fantasies for most of the 20th century. I envisioned weaving that theme into the life story of Elizabeth Taylor, who grew up as a little girl at MGM, and went to school at MGM and . . . married many MGM men. But my plan for this historical narrative soon got buried in Ms. Taylor’s Technicolor life of husbands and hospitals and jewelry stores.

My agent asked, if I were to consider writing another life story, who would be of interest? I said, “Well, the gold ring on the merry-go-round would be Frank Sinatra, because no one’s really done it, and he epitomizes the American dream.” She agreed and that was the end of the subject until a couple weeks later when she called and said she had a generous offer from Bantam Books.

Soon I was back in the biography business, thinking I’d paid my hard luck dues. I’d had a bandit publisher on my first book and a thieving agent on my second. Now was third time lucky. And for a few weeks it was . . . until I was served a subpoena from Frank Sinatra, announcing that he was suing me for $2 million dollars for usurping the rights to his life story. He claimed that he and he alone (or someone he authorized) was entitled to write his life story, and I certainly had not been authorized.

I immediately called my publisher, and Bantam’s legal counsel informed me that I was on my own. “Mr. Sinatra has not sued us,” she said. “He’s sued you, and since you’ve not given us a manuscript, we’re not involved. So, I’d advise you to get legal counsel in California, which is where you’ve been sued and do keep us informed.”

“But I haven’t written a word. I’ve only just begun. My manuscript is years away.”

“We’ll talk then,” she said, before hanging up.

Now, getting sued by a billionaire with Mafia ties concentrates the mind, especially after your publisher leaves the scene. I called my friend, the president of Washington Independent Writers, to commiserate. “I wish we could help you, Kitty, but we’re almost broke,” she said. I assured her that I wasn’t looking for money—just moral support. “Well, in that case, let me get on the horn.” She contacted several writers’ groups, including the Authors Guild and PEN and the American Society of Journalists and Authors, and Sigma Delta Chi, and the National Writers Union. Days later, they held a press conference at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., to denounce Sinatra for using his power and influence to intimidate a writer before she’d written a word. They denounced his lawsuit and his assault on the First Amendment. As journalists, they understood what was at stake if Sinatra prevailed.

I retained the law firm of O’Melveny and Myers in Los Angeles and tried to keep working on the book, but was interrupted a few weeks later when I was in New York doing interviews and my lawyer called to tell me to get back to D.C. because the LA lawyers were coming to Washington for a meeting that would also be attended by my publisher. The LA lawyers said they’d received a tape recording from Sinatra’s lawyers of me supposedly misrepresenting myself as Sinatra’s authorized biographer, and this tape recording was the proof that they were going to present in court.

Now I was scared, even though I knew I hadn’t made such a telephone call. But I began to second-guess myself, wondering if maybe under the pressure I’d snapped my cap. By the time the lawyers arrived that Monday morning I was ready for handcuffs.

Three teams of lawyers sat down in my living room and put the tape in the recorder. No one said a word for the first two minutes because what we heard sounded like Porky Pig flying high on helium. In a squeaky voice, Porky said he was me and Frank Sinatra told me to call for an interview. The lawyers played that tape three times and we all listened to Porky Pig again and again before anyone said a word. Then all the lawyers laughed, clearly relieved, knowing the tape was a phony. I didn’t laugh.

“This lawsuit has gone on for almost a year and now someone is willing to lie under oath to say that I misrepresented myself to get an interview.”

“Don’t worry. We’ll send this to the tape labs at U.S.C., they’ll send the report to Sinatra’s team, and we’ll file for a dismissal. Meantime, just tape all your interviews.”

I tried to explain to the lawyers that you couldn’t always tape interviews, especially in the early 1980’s, when the technology wasn’t sophisticated. Taping in restaurants was difficult over the clinking of glasses, and taping phone interviews wasn’t legal in every state, even with two-party permission.

I finally decided that the best way to protect myself was to write a thank-you note to everyone I interviewed. That turned out to be 800 notes. They were polite and also protective. I’d thank them for the time they gave me in their home or their office or their favorite bar—wherever we’d done the interview; I’d compliment them on the polka dot bow tie they wore or the pretty pink blouse or their red tennis shoes; I’d mention the fabulous décor, or a particular piece of art, or our great salad in such-and-such a restaurant—any detail that set the time or place. Then I’d send it off and keep a copy in my files, because three or four years later when the book was finally published, they might very well have forgotten that interview or, more likely, wish they had.

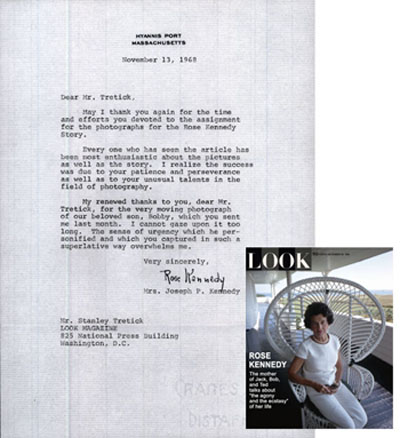

That happened with Frank Sinatra Jr. He’d agreed to be interviewed when he was performing in Washington, D.C. His representative asked if I’d be bringing a camera crew, and I said no crew, just a still photographer. Then I quickly called my friend Stanley Tretick, one of President Kennedy’s favorite photographers who had worked for UPI and then LOOK magazine.

Stanley and I arrived at the Capitol Hill Hilton in the afternoon and went to Sinatra’s suite. His publicist met us and then disappeared when Frank Jr. entered the room. Sinatra’s only son sat down and asked me to sit close to him because he didn’t want to strain his voice. He was performing that night. So, I moved over, notebook in hand. The first 30 minutes of the interview went well as Sinatra Jr. talked about accompanying his father on tour and hanging out in Vegas with his father’s friends. Then he leaned over and said, “Hon, I know what happened to Jimmy Hoffa.”

I didn’t move. Because no one knew what happened to Jimmy Hoffa. They knew he was dead, but they didn’t know how or by whom. And now the son of a mob-connected man was going to tell me.

For a split second I wondered what I should wear when I got the Pulitzer Prize.

Just as Frank Sinatra Jr. leaned over to whisper in my ear, Stanley dropped his camera bags on the floor, and said, “Well out with it, man. What the hell happened to Hoffa?”

Frank Sinatra Jr. reared back as if he’d been clubbed. He looked at me, then he bolted from his chair and ran into the bedroom, slamming the door. His publicist came running out and said we had to leave. I begged for more time, saying the interview wasn’t finished, but the publicist was physically pushing us out the door.

Up to that point, Stanley Tretick had been one of my closest friends. Now I looked at him as if he’d just been possessed by the Tasmanian devil.

“Aw, hell. He doesn’t know what happened to Jimmy Hoffa.”

“Really?” I said. “And since when are photographers clairvoyant? And what kind of a lunkhead photographer throws a hissy in the middle of a reporter’s interview? Did it ever occur to you that what the son of a mob-connected man has to say about the disappearance of Jimmy Hoffa might be of interest?”

By now I was down the steps and storming the street to hail a cab. I refused to ride in the same car with a crazy person when I was homicidal. I didn’t speak to Stanley for some time, but he became my best pal again when the Sinatra biography was published. By then Frank Sinatra had dropped his lawsuit but his son now decided to sue, denying he’d ever given me an interview. His lawyers contacted my publisher and everyone braced for another lawsuit. But Stanley produced one of the photos he’d taken during our interview that showed me sitting next to Frank Sinatra Jr. with a notebook in [my] hand and a tape recorder on the table.

That photograph certainly trumped all of my little thank-you notes. Yet I can’t tell you how many times those notes saved me. When I wrote the Nancy Reagan biography, letters rained down on Simon & Schuster from corporate tycoons and all manner of political operatives, who took offense with the words attributed to them or to their wives or secretaries or associates, and at the bottom of every letter was a “cc” to President Ronald Reagan. Each time the publisher’s lawyer would call me to go over my notes and my tapes, and then he’d send a courteous reply, saying the publisher stands by the book and its accuracy.

At first, I wanted the publisher to “cc: President Reagan” just like all the letter writers had done, but the lawyer said no reason to stir the beast. “Those are weasel letters. They’re sent simply to show the flag.” He was right, and there were no retractions and no lawsuits.

That controversial biography became the cover of Time, Newsweek, People, Entertainment Weekly, and The Columbia Journalism Review, and [was] presented on the front pages of The New York Times, The New York Post, and the New York Daily News.

On the day of publication, President and Mrs. Reagan held a press conference to denounce the book, saying that I had—quote—“clearly exceeded the bounds of decency.” And three days later, President Richard Nixon agreed. President Nixon wrote a letter to President Reagan to commiserate. President Reagan responded, saying that everyone he knew had denied talking to the author. Reagan even named the minister of his church, who’d been cited as a source, and the minister had written a denial to all his parishioners in the Bel Air Presbyterian Church bulletin.

Now, I really tried not to respond to every accusation, but this one from a man of the cloth got to me, and I wrote to remind him of the 45 minute interview he’d given in his office. I enclosed a transcript of his taped remarks and asked him to please send around another church bulletin—with a correction. Of course, he didn’t, which proves the wisdom of Winston Churchill, who said that a lie flies halfway around the world before the truth gets its pants on.

Having rankled President Reagan and President Nixon, I later rattled President George Herbert Walker Bush. I’d written to him as a matter of courtesy, when I was under contract to Doubleday to write a historical retrospective of the Bush family, and said I’d appreciate an interview sometime at his convenience.

President Bush never responded to me but he directed his aide to write my publisher, saying:

“President Bush has asked me to say that he and his family are not going to cooperate with this book because the author wrote a book about Nancy Reagan that made Mrs. Reagan unhappy.” First Lady Barbara Bush had been so incensed when she saw my books displayed in the First Ladies Exhibit at the Smithsonian that she directed the curator to remove the display, which he did the next day. In fact, I might not have known about it had I not taken my niece to the Smithsonian a few weeks before and we’d seen the display and took a picture of it.

That photograph now hangs in my guest bathroom next to autographed cartoons from Jules Feiffer and Garry Trudeau. Over the years, that loo has become crowded with cartoons from all of my various books. My sister was very impressed when she saw them. She said to my husband, “I think it’s great that Kitty has put up all the bad ones.” My husband said, “There were no good ones.”

My biography on the Bush family dynasty was published in 2004, in the midst of a contentious presidential campaign. Bush Jr. was running for a second term, and I was lambasted by his White House press secretary, the White House deputy press secretary, the White House communications director, the Republican National Committee, and the house majority leader, Tom DeLay. Mr. DeLay even wrote a colorful letter to my publisher, saying that I was—quote—“in the advanced stage of a pathological career” and the publisher was in—quote—“moral collapse for publishing such a scandalous enterprise.”

When the Bush book became number one on the New York Times bestseller list, I was dropped from the masthead of The Washingtonian Magazine, where I’d been a contributing editor for 30 years. The new owner of the magazine was a Bush presidential appointee. The editor told me, “Your book was too personal. Too revealing.”

“But that’s what a biography is,” I said. “It’s an intimate examination of a person in his times, and in this case a powerful person in the public arena. The President of the United States influences our society, with actions that affect our lives.”

I quoted the actor Melvyn Douglas from the movie Hud. He talked about the mesmerizing power of a public image: “Little by little the look of the country changes because of the men we admire.” And Colum McCann, in his novel Let the Great World Spin, wrote: “Repeated lies become history, but they don’t necessarily become the truth.”

This is why biography is so vital to a healthy society. Whether authorized or unauthorized, biography presents a life story—sometimes it’s an x-ray of a manufactured image, sometimes it’s a gauzy bandage. The best biographers try to penetrate dross and drill for gold. As President Kennedy said, “The great enemy of the truth is very often not the lie—deliberate, contrived and dishonest—but the myth, persistent, persuasive, and unrealistic.”

I do not relish living in a world where information is authorized, sanitized, and homogenized. I read banned books. I applaud whistleblowers and I reject any suppression by church or state. To me, the unauthorized biography, which requires a combination of scholarly research and investigative reporting, is best directed at those figures still alive and able to defend themselves, who exercise power over our lives. . . . I firmly believe that unauthorized biography can be a public service and a boon to history.

The most solid support I’ve received over the years has come from writers—journalists and historians and biographers—who believe in the First Amendment. Who champion the public’s right to know.

These are principles that feed my soul and fill my heart, which is why I’m so grateful to be honored by you today with this award.

Thank you.

King: A Life

by Kitty Kelley

They said one to another

Behold here cometh the Dreamer

Let us slay him

And we shall see what will become of his dreams.

– Genesis 37:19-20

These words are carved into the cement plaque that rests outside room 306 of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. They mark the place where Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968. The dreamer’s death transformed his murder site into a shrine that now houses the National Civil Rights Museum, where King’s life continues to inspire, drawing thousands of visitors every year.

These words are carved into the cement plaque that rests outside room 306 of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. They mark the place where Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968. The dreamer’s death transformed his murder site into a shrine that now houses the National Civil Rights Museum, where King’s life continues to inspire, drawing thousands of visitors every year.

Scholars and historians have long explored the legacy of the Baptist minister from Georgia who preached a gospel of nonviolence. Deservedly, many King biographies have won prestigious prizes, among them Taylor Branch’s magisterial trilogy: Parting the Waters, Pillar of Fire, and At Canaan’s Edge. Additional tributes to King include I May Not Get There with You by Michael Eric Dyson; Bearing the Cross by David J. Garrow; Let the Trumpet Sound by Stephen B. Oates; Death of a King by Tavis Smiley; The Promise and the Dream by David Margolick; and The Sword and the Shield by Peniel E. Joseph.

Now comes Jonathan Eig with King: A Life, which promises “to recover the real man from the gray mist of hagiography.” Regrettably, says the author, “In the process of canonizing King, we’ve defanged him…[but] King was a man, not a saint, not a symbol.” In removing the mantle, Eig presents here an orator of soaring rhetoric who unapologetically plagiarized his speeches, saying his goal was to move audiences. Even King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech seems to have had its origins in Langston Hughes’ poems “I Dream a World” and “Dream Deferred.”

Misappropriating others’ work is a grievous sin for scholars, a “bad habit,” Eig writes, that King started in high school and continued as a graduate student at Crozier and later at Boston University, where he earned his Ph.D. with a dissertation that contained more than 50 sentences lifted from someone else’s work. By contrast, readers will note how generous Eig is to his own sources, giving previous biographers their due and quoting many by name in his text, not simply relegating them to chapter notes in the back of the book. Just as noteworthy is Eig’s appreciation for all who contributed to King: A Life; he lists each name under “Acknowledgements: Beloved Community.”

In this biography, his sixth book, Eig writes like an Olympic diver who jackknifes off the high board, slicing the water without a ripple. He performs with sheer artistry, like Picasso paints and Astaire dances. In unspooling the life of King, Eig presents a complicated man who attempted suicide twice; who was plagued by clinical depression so deep it required hospitalization; who chewed his nails; and who gave up the “true love” of his life, a white woman named Betty Moitz, because he realized, with her, he would never be accepted as a preacher in Black churches. The late Harry Belafonte, who himself married a white woman, told Eig that King never stopped talking about Moitz, and King’s mentor in graduate school described him after the break-up as “a man with a broken heart,” adding, “he never recovered.”

Although he married Coretta Scott and had four children with her, King pursued many women throughout his life. While Eig is unsparing about those extramarital affairs, he writes gently: “King’s busy schedule of travel also afforded him opportunities to spend time with women other than Coretta.”

The author also draws interesting similarities between King and John F. Kennedy, both of whom indelibly marked their era:

- Both were influenced by powerful (and philandering) fathers.

- Both enjoyed a privileged lifestyle above their contemporaries.

- Both were accused of plagiarism.

- Both experienced discrimination (JFK as an Irish Catholic; King as a Black man).

- Both excelled as public speakers.

- Both were assassinated.

King was particularly threatened by the never-made-public tape recordings FBI director J. Edgar Hoover ordered, turning federal agents into bloodhounds and instructing them to install bugs wherever King traveled. Hoover distributed copies of the recordings, which contained evidence of “unnatural sexual acts,” to President Lyndon Johnson, White House officials, and journalists in order to undermine King’s credibility. To further ensure his ruin, Hoover met with a group of woman journalists and declared King the country’s “most notorious liar.”

King reportedly wept over the slur to his life’s work but managed a masterful response to the press:

“I cannot conceive of Mr. Hoover making a statement like this without being under extreme pressure. He has apparently faltered under the awesome burden, complexities and responsibilities of his office. Therefore, I cannot engage in a public debate with him. I have nothing but sympathy for this man who has served his country well.”

By opposing the “immoral” war in Vietnam, King, who’d received the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize, drew the unremitting ire of Johnson. As Eig writes, King’s “conscience would not allow him to cooperate with an advocate and purveyor of war.” Infuriated, Johnson never forgave the man who’d given his presidency its three greatest legislative achievements: the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

While Eig reveals the flawed man behind the myth, Martin Luther King Jr. still stands tall and strong enough to shoulder Shakespeare’s words from “Measure for Measure”:

They say best men are molded out of faults,

And, for the most, become much more the better

For being a little bad

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

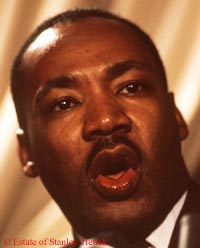

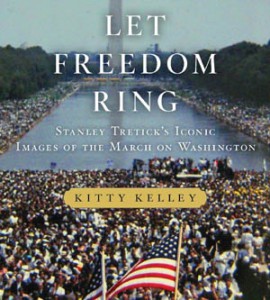

(Color photo of Martin Luther King Jr. by Stanley Tretick, 1966, from Let Freedom Ring.)

“Martin’s Dream Day” Chosen for ILA Teachers’ Choices Reading List

The International Literacy Association (ILA) on May 1, 2018 announced the winning titles of the 2018 Choices reading lists: an annual selection of outstanding new children’s and young adults’ books, curated by students and educators themselves. These lists are issued during Children’s Book Week each year.

The International Literacy Association (ILA) on May 1, 2018 announced the winning titles of the 2018 Choices reading lists: an annual selection of outstanding new children’s and young adults’ books, curated by students and educators themselves. These lists are issued during Children’s Book Week each year.

This year, Martin’s Dream Day by Kitty Kelley was included as a Teachers’ Choice for Intermediate Readers (ages 8-11).

Each year, thousands of children, young adults, and educators around the United States select their favorite recently published books for the International Literacy Association’s Choices reading lists. These lists are used in classrooms, libraries, and homes to help readers of all ages find books they will enjoy.

The International Literacy Association (ILA) is a global advocacy and membership organization dedicated to advancing literacy for all through its network of more than 300,000 literacy educators, researchers and experts across 78 countries. With over 60 years of experience, ILA has set the standard for how literacy is defined, taught and evaluated. ILA collaborates with partners across the world to develop, gather and disseminate high-quality resources, best practices and cutting-edge research to empower educators, inspire students and inform policymakers. ILA publishes The Reading Teacher, Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy and Reading Research Quarterly.

The International Literacy Association (ILA) is a global advocacy and membership organization dedicated to advancing literacy for all through its network of more than 300,000 literacy educators, researchers and experts across 78 countries. With over 60 years of experience, ILA has set the standard for how literacy is defined, taught and evaluated. ILA collaborates with partners across the world to develop, gather and disseminate high-quality resources, best practices and cutting-edge research to empower educators, inspire students and inform policymakers. ILA publishes The Reading Teacher, Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy and Reading Research Quarterly.

“Martin’s Dream Day” is Woodson Honor Winner

National Council for the Social Studies “established the Carter G. Woodson Book Awards for the most distinguished books appropriate for young readers that depict ethnicity in the United States. First presented in 1974, this award is intended to ‘encourage the writing, publishing, and dissemination of outstanding social studies books for young readers that treat topics related to ethnic minorities and race relations sensitively and accurately.’”

2018

Elementary Level Honoree

Martin’s Dream Day

by Kitty Kelley

Atheneum Books for Young Readers

Kitty Kelley Publishes Her First Children’s Book

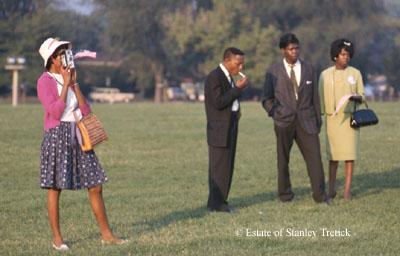

Kitty Kelley’s first book for children will be published January 3, 2017 by Atheneum Books for Young Readers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing. Martin’s Dream Day tells the story of the 1963 March on Washington, illustrated by Stanley Tretick’s photography.

“Martin Luther King dreamed of making justice a reality for all God’s children so it seemed right to share the images of his dream day with children,” said Kelley.

Ages 5 and up.

Read press release here.

Kitty Kelley will donate her proceeds from this book to Reading Is Fundamental, the largest nonprofit children’s literacy organization in the United States.

Buy in hardcover or in ebook format.

Kitty Kelley on Book-TV

Kitty Kelley appeared on C-Span2’s Book-TV “In Depth” program on Sunday, Nov. 3, 2013, answering questions from host Peter Slen and from viewers for three hours. The show may be viewed online here.

The March to the Dream

by Kitty Kelley

President Kennedy had to be pushed but after two bloody summers of Freedom Riders, television coverage of Bull Connors’ police dogs chewing children to bits, police men clubbing peaceful demonstrators and fire hoses slamming children against jagged brick buildings, leaving them torn and bleeding, JFK found his voice. He watched with disgust as Alabama Governor George Wallace, who had pledged “Segregation now. Segregation tomorrow. Segregation forever,” threatened to stand in the school house door to prevent two black students from integrating the state’s all-white university. That evening, June 11, 1963, John F. Kennedy ennobled his presidency with an address to the nation on equal rights:

President Kennedy had to be pushed but after two bloody summers of Freedom Riders, television coverage of Bull Connors’ police dogs chewing children to bits, police men clubbing peaceful demonstrators and fire hoses slamming children against jagged brick buildings, leaving them torn and bleeding, JFK found his voice. He watched with disgust as Alabama Governor George Wallace, who had pledged “Segregation now. Segregation tomorrow. Segregation forever,” threatened to stand in the school house door to prevent two black students from integrating the state’s all-white university. That evening, June 11, 1963, John F. Kennedy ennobled his presidency with an address to the nation on equal rights:

We are confronted primarily with a moral issue. It is as old as the Scriptures and as clear as the American Constitution…. If an American, because his skin is dark, cannot eat lunch in a restaurant open to the public, if he cannot send his children to the best schools available, if he cannot vote for the public officials who represent him…then who among us would be content to have the color of his skin changed? Who among us would then be content with counsels of patience and delay?

Next week I shall ask the Congress of the United States to make a commitment it has not fully made in this country to the proposition that race has no place in American life or law.

The President’s approval plummeted from 60 to 47 percent after his speech, and he and his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, began counseling “patience and delay,” pleading with Civil Rights leaders to call off their scheduled March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Fearing violence and re-election in 1964, the administration said the March would do more harm than good. “We want success in Congress, not a big show at the Capital,” said the President.

The President’s approval plummeted from 60 to 47 percent after his speech, and he and his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, began counseling “patience and delay,” pleading with Civil Rights leaders to call off their scheduled March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Fearing violence and re-election in 1964, the administration said the March would do more harm than good. “We want success in Congress, not a big show at the Capital,” said the President.

Kennedy summoned Civil Rights leaders to the White House to try to dissuade them but they remained resolute. The President relented and then called his brother: “Well, if we can’t stop them, we’ll run the damned thing.”

The March organizers agreed to demonstrate on a Wednesday so people would get back to their jobs and not stay the week-end. Parade permits were granted from 9 a.m to 5 p.m so that marchers would leave the city before dark. Schools, bars, restaurants and stores were closed. All elective surgeries in area hospitals were cancelled to free up 340 beds for riot-related emergencies.  The DC National Guard spent the summer training for riot duty and 2400 Guardsmen were sworn in as “special officers” with temporary arrest power. The city, including leaders like Mrs. Agnes E. Meyer, whose family owned The Washington Post and Newsweek, predicted “catastrophic outbreaks of violence, bloodshed and property damage.” The government closed the day of the March and federal employees were told to stay home.

The DC National Guard spent the summer training for riot duty and 2400 Guardsmen were sworn in as “special officers” with temporary arrest power. The city, including leaders like Mrs. Agnes E. Meyer, whose family owned The Washington Post and Newsweek, predicted “catastrophic outbreaks of violence, bloodshed and property damage.” The government closed the day of the March and federal employees were told to stay home.

The comedian Dick Gregory was amused by the fears of the white establishment. “I know the senators and congressmen are scared of what’s going to happen,” he said. “[But] I’ll tell you what’s going to happen. It’s going to be a great Sunday picnic.” To the Kennedy administration it looked like it was going to be a great big political fiasco.

Weeks in advance, the March, set for August 28, 1963, became global news as Civil Rights activists around the world announced that they, too, would march in Berlin, Munich, Amsterdam, London, Oslo, Madrid, The Hague, Tel Aviv, Cairo, Toronto, and Kingston, Jamaica.  Celebrities chartered planes from Hollywood’s progressive community, including Harry Belafonte, Paul Newman, Marlon Brando, Gregory Peck, Billy Eckstein, Lena Horne, Sidney Poitier, Sammy Davis, Jr., Tony Bennett, even Charleton Heston. Burt Lancaster flew from his movie location in Paris, and the dancer and jazz singer Josephine Baker arrived from France in her Free French uniform.

Celebrities chartered planes from Hollywood’s progressive community, including Harry Belafonte, Paul Newman, Marlon Brando, Gregory Peck, Billy Eckstein, Lena Horne, Sidney Poitier, Sammy Davis, Jr., Tony Bennett, even Charleton Heston. Burt Lancaster flew from his movie location in Paris, and the dancer and jazz singer Josephine Baker arrived from France in her Free French uniform.

Even with unprecedented police presence on the Mall, the President was so concerned about hot rhetoric stirring the crowds to violence that he positioned one of his advance men behind the sound system at the Lincoln Memorial ready to flip a special switch to cut the public address system, if necessary, and play a recording of Mahalia Jackson singing, “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands.”

The day dawned with Washington’s usual summer swamp humidity but most of the 250,000 marchers arrived in their Sunday best. Women donned hats and high heels; men wore white shirts and ties. They dressed for church; their mission was religious—to heal sick hearts and open closed minds.

They marched and sang and swayed to the soaring sounds of the Freedom Singers and Odetta and Marian Anderson; they sat ten- deep at the Reflecting Pool, many dangling their feet in the water like pilgrims who once gathered at the Sea of Galilee.

They cheered the speakers, and then they rose and roared in unison for the spell-binding finale of Martin Luther King, Jr., who had come to tell them about his dream for America “that one day the nation will rise up and live out the true meaning

of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’”

of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’”

The vast throng of humanity erupted into thunderous applause with each crescendo of Dr. King’s dream. In the rising cadence of a master spell-binder, he told America that if it was to become a great nation, it must make the dream of freedom come true for its black citizens. Even President Kennedy, watching on television, was transfixed. “He’s good. He’s damn good.”

The President had refused to participate in the March, but he invited the Civil Rights leaders to the White House at the end of the day. He greeted Dr. King by shaking his hand and saying, “I have a dream.”

Bubbling over with the success of the day which had occurred without one incident of violence, the President told reporters that he was edified by the speeches, the singing, the crowds—the entire event. “The nation can be properly proud of this march,” he said.

Photos from Let Freedom Ring: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the March on Washington, ©Estate of Stanley Tretick, used with permission.

Buy: Amazon Barnes & Noble Books-A-Million Apple IndieBound

Cross-posted from Huffington Post

Rose Kennedy: The Life and Times of a Political Matriarch

by Kitty Kelley

Anyone who has followed the Kennedys knows the bar is high for books on the subject. Having been inundated for the past 50 years with hundreds of biographies and memoirs and profiles about the spellbinding mystique of John Fitzgerald Kennedy, his family and his thousand days as the country’s first Irish-Catholic president, we expect each publication to bring something new and fresh to add to our understanding of the family that refashioned politics in the 20th century.

Anyone who has followed the Kennedys knows the bar is high for books on the subject. Having been inundated for the past 50 years with hundreds of biographies and memoirs and profiles about the spellbinding mystique of John Fitzgerald Kennedy, his family and his thousand days as the country’s first Irish-Catholic president, we expect each publication to bring something new and fresh to add to our understanding of the family that refashioned politics in the 20th century.

Serious historians (Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., William Manchester, James MacGregor Burns, Nigel Hamilton), journalists (Seymour Hersh, Jack Newfield, Warren Rogers), conspiracy theorists (Jim Garrison), commercial clip-and-pasters (Laurence Leamer, Christopher Anderson) and friends (Paul “Red” Fay, Benjamin C. Bradlee) have tried to capture the firefly magic of the Kennedys, while antagonists (Victor Lasky, Ralph de Taledano) have tried to puncture their myth.

So now comes Barbara A. Perry with Rose Kennedy: The Life and Times of a Political Matriarch, who promises to deliver “the definitive biography” of the woman whose iron-fisted image-making produced the mystique that continues to endure. When the John F. Kennedy Library released the papers of the president’s mother (300 boxes) in 2006, Perry, a senior fellow in presidential oral history at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center in Charlottesville, was first in line, but, alas, Rose had no secrets beyond the few she revealed in her 1974 memoir, Times to Remember. As a biographer Perry was challenged. After six years of research and writing, she bowed to the obvious: With nothing new, she went for nuance. Her text is well written and her bibliography shows research, but there is no gold in the mine.

Her book cover, though, is perfect, absolutely perfect, because it captures the essence of Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy. The black-and-white photograph shows a woman who later died at the age of 104 after living her life by the black-and-white strictures of the Catholic Church, pre-Vatican II. Still glamorous at the age of 73, she is sitting next to the handsome president at a White House state dinner in 1963. She is acting as her son’s hostess because the first lady is away on one of her many vacations, similar to the ones Rose took for six to eight weeks at a time to get away from the clamor of her large family, and possibly, according to her biographer, as a means of Church-approved birth control. Rose is wearing the Molyneux gown she wore when she was 48 and her husband, Joseph P. Kennedy, was presented to the king and queen of England as the U.S. ambassador to the Court of St. James. That was the crowning glory of Rose’s life: To be accepted by British royalty was beyond the biggest dreams of a little girl from Dorchester, Mass.

Her book cover, though, is perfect, absolutely perfect, because it captures the essence of Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy. The black-and-white photograph shows a woman who later died at the age of 104 after living her life by the black-and-white strictures of the Catholic Church, pre-Vatican II. Still glamorous at the age of 73, she is sitting next to the handsome president at a White House state dinner in 1963. She is acting as her son’s hostess because the first lady is away on one of her many vacations, similar to the ones Rose took for six to eight weeks at a time to get away from the clamor of her large family, and possibly, according to her biographer, as a means of Church-approved birth control. Rose is wearing the Molyneux gown she wore when she was 48 and her husband, Joseph P. Kennedy, was presented to the king and queen of England as the U.S. ambassador to the Court of St. James. That was the crowning glory of Rose’s life: To be accepted by British royalty was beyond the biggest dreams of a little girl from Dorchester, Mass.

Bejeweled with two diamond clips in her hair, diamonds dripping from her ears, a triple strand of pearls the size of grapes circling her unlined neck and a bracelet of diamonds wrapped around her arm, which is encased in a long white kid-leather glove, Rose is whispering in her son’s ear.  Ever the canny pol, she covers her mouth so the photographer cannot catch a candid shot. (“I do not like candid pictures,” she said. “They are so unattractive.”)

Ever the canny pol, she covers her mouth so the photographer cannot catch a candid shot. (“I do not like candid pictures,” she said. “They are so unattractive.”)

Oh, did I mention that the Molyneux gown was sleeveless? This is a detail Rose would want to have emphasized because she prided herself on her petite figure and frequently said that after having nine children she could still wear a size 8. Her frenetic exercise routine of swimming in the ocean every day, playing golf, walking miles, eating sparingly and rarely drinking had left her sleek and svelte with tanned, taut arms.

Appearances ruled Rose, and nothing mattered to her as much as how one looked — in person and in pictures. She made her children line up for daily inspections so she could see if their shoes were shined and their buttons attached. She saw each child as a reflection of herself and of the family name her husband was making famous on Wall Street and in Hollywood, so she strove for perfection, demanding it of herself and everyone around her. A martinet mother, she insisted her children brush their teeth three times a day and say their prayers every night. They were instructed to make meals on time or go without eating, and en route to the dining room they were required to check the bulletin board for the topics of current affairs that were to be discussed at dinner. Rose was the parent in charge of their childhood. When they became young adults her husband took over, but as one daughter said, “Dad gave us many lovely things but mother gave us our character.”

Despite her foibles and her husband’s philandering Rose relied on her strong religious faith to survive the worst tragedies of her life, and she managed to produce an extraordinary family of sons and daughters, who cared for each other, supported each other and remained close throughout their lives — and that is a mother’s finest legacy. Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy is an admirable subject but one that left her admiring biographer empty-handed.

Kitty Kelley’s seven biographies include Jackie Oh! (1978), the first book to reveal that the former first lady suffered from depression and was treated with electroshock therapy; it also reported for the first time that Rosemary Kennedy survived the mangled lobotomy her father had ordered in hopes of reversing her mental retardation. In 1988, People published Kelley’s story detailing President Kennedy’s affair with a woman who carried his messages to her other lover, mobster Sam Giancana.

Kitty Kelley’s seven biographies include Jackie Oh! (1978), the first book to reveal that the former first lady suffered from depression and was treated with electroshock therapy; it also reported for the first time that Rosemary Kennedy survived the mangled lobotomy her father had ordered in hopes of reversing her mental retardation. In 1988, People published Kelley’s story detailing President Kennedy’s affair with a woman who carried his messages to her other lover, mobster Sam Giancana.

Cross-posted with Washington Independent Review of Books.

Photos from Capturing Camelot ©Estate of Stanley Tretick, used with permission.

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

Bestselling author Kitty Kelley goes behind the lens of legendary Look photographer Stanley Tretick to capture a pivotal moment in our nation’s history: The March on Washington, August 28, 1963. Most of these extraordinary photos have never been seen before.

Bestselling author Kitty Kelley goes behind the lens of legendary Look photographer Stanley Tretick to capture a pivotal moment in our nation’s history: The March on Washington, August 28, 1963. Most of these extraordinary photos have never been seen before.

Let Freedom Ring: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the March on Washington will be published by Thomas Dunne Books in August 2013 in hardcover and ebook formats.

Preorder: Amazon Barnes & Noble Books-A-Million Apple IndieBound

Camelot

by Kitty Kelley

John F. Kennedy continues to reign as the most popular president of the twentieth century, according to recent Gallup polls. (Richard Nixon and George W. Bush remain the most unpopular). Most historians agree that Abraham Lincoln was the most important man to ever occupy the White House because he abolished slavery and kept the states united through a bloody civil war. Yet for most Americans, Kennedy, whose presidential accomplishments were slight, continues to glisten like a shamrock after a spring rain.

For those alive in 1963 this month casts a shadow of sadness as we recall where we were on November 22 when we heard about the president’s assassination. We remember the weekend binge of television coverage — the stalwart widow in her black veil, the riderless horse, the little boy’s salute to his father’s coffin and the eternal flame, which draws over 500,000 visitors a year to Arlington National Cemetery.

Beginning last year we mark the 50th anniversary of the Kennedy administration — the thousand days which J.F.K. defined as the New Frontier, a time when he said the torch was passed to a new generation. We were told to ask not what our country could do for us but what we could do for our country, and he showed us how by establishing the Peace Corps so Americans could do something positive and lasting. Since 1961 more than 210,000 volunteers have served in 139 countries.

Yet it is for something far less tangible that John F. Kennedy continues to be revered. Elected fifteen years after the end of WWII, he captured the spirit of those times. He radiated the excitement of change and the optimism of expectation. He broke the barriers of religious bigotry by becoming the first Catholic to be elected president, thereby making us believe that anything was possible, even sending a man to the moon and back within a decade. He moved further than his predecessors on civil rights by declaring that equality under the law was a moral issue “as old as the Scriptures and as clear as the Constitution.” He believed in horizons without limits. “No problem of human destiny is beyond human beings,” he said, speaking about the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty which was signed in August 1963.

Yet it is for something far less tangible that John F. Kennedy continues to be revered. Elected fifteen years after the end of WWII, he captured the spirit of those times. He radiated the excitement of change and the optimism of expectation. He broke the barriers of religious bigotry by becoming the first Catholic to be elected president, thereby making us believe that anything was possible, even sending a man to the moon and back within a decade. He moved further than his predecessors on civil rights by declaring that equality under the law was a moral issue “as old as the Scriptures and as clear as the Constitution.” He believed in horizons without limits. “No problem of human destiny is beyond human beings,” he said, speaking about the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty which was signed in August 1963.

John F. Kennedy brought style and charisma to the White House and a first family that captivated the country: a handsome, witty president, an elegant first lady, and two adorable young children. While his image was later tarnished by revelations of marital infidelity and reckless behavior, polls show that he still holds the public in thrall. Herbert Parmet, one of his many biographers, claimed he was nothing but glamour and gloss, and dismissed him as an “interim president who had promised but not performed.” Yet there is no way to diminish the nation’s nostalgia for this man who was felled in his prime, and became an enduring legend. No other president has left a larger footprint on his country than John F. Kennedy, who to date is honored by 149 institutions which carry his name — schools, hospitals, clinics, concert halls, arts centers and an international airport, proving perhaps that promise is as inspiring as performance.

John F. Kennedy brought style and charisma to the White House and a first family that captivated the country: a handsome, witty president, an elegant first lady, and two adorable young children. While his image was later tarnished by revelations of marital infidelity and reckless behavior, polls show that he still holds the public in thrall. Herbert Parmet, one of his many biographers, claimed he was nothing but glamour and gloss, and dismissed him as an “interim president who had promised but not performed.” Yet there is no way to diminish the nation’s nostalgia for this man who was felled in his prime, and became an enduring legend. No other president has left a larger footprint on his country than John F. Kennedy, who to date is honored by 149 institutions which carry his name — schools, hospitals, clinics, concert halls, arts centers and an international airport, proving perhaps that promise is as inspiring as performance.

Photos © Estate of Stanley Tretick, LLC, used with permission.

Cross-posted from Huffington Post