Capturing Camelot

Jackie, Janet & Lee

by Kitty Kelley

Nothing sells like sex, diets, and the Kennedys. A book entitled How JFK Made Love to Marilyn Monroe on 150 Calories a Day would zoom to instant success. Just ask J. Randy Taraborrelli, who’s been mining two of those veins for the last 20 years and claims “many New York Times best sellers” to his credit.

Nothing sells like sex, diets, and the Kennedys. A book entitled How JFK Made Love to Marilyn Monroe on 150 Calories a Day would zoom to instant success. Just ask J. Randy Taraborrelli, who’s been mining two of those veins for the last 20 years and claims “many New York Times best sellers” to his credit.

In 2000, he wrote Jackie, Ethel, Joan: The Women of Camelot, which became a two-part TV series on NBC in 2001. He wrote After Camelot in 2012, and he now offers Jackie, Janet & Lee: The Secret Lives of Janet Auchincloss and Her Daughters Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and Lee Radziwill.

Spoiler alert: He adores Jackie and abhors Lee. The big reveal, according to his publisher’s press release, is that (supposedly) their mother performed do-it-yourself artificial insemination to get pregnant twice after she divorced their father and married her second husband, Hugh D. Auchincloss.

Janet was 37; Hugh was 58, and he had had three children by two previous wives. Yet we’re told to believe that Mr. Auchincloss was incapable of impregnating Mrs. Auchincloss in 1945 and again in 1947. And — hang on — we’re told why: “Even though Hugh was not able to sustain an erection, he was able to produce sperm…[and Janet] used a kitchen utensil along the lines of a turkey baster — though it would be incorrect to say that this was the specific instrument she used; no one can quite remember…”

With eyes popping, I turned to the chapter notes for documentation on this “never before revealed secret.” Under source notes for “Janet’s Unconventional Pregnancy,” Taraborrelli writes: “Because of the sensitive nature of this chapter, my interviewed sources asked to remain anonymous.”

Huh?

With Mr. and Mrs. Auchincloss deceased for many years, I wondered what possible “sources” could’ve been interviewed about the intimacies of their bedroom. No documentation is provided, other than the author’s note that he recycles sources from his previous books. Then, like a bird feathering its nest, he snatches twigs and wisps from newspapers, magazines, and tabloids while plucking from the vast trove of other published lore, which Jill Abramson, in the New York Times, once estimated to be 40,000 Kennedy books.

In this book, some readers might be troubled by the lack of attribution for “she felt,” “he thought,” “said an intimate,” “revealed an associate,” “confided an employee,” and “reported someone with knowledge of the situation.”

Others might be puzzled by the personal quotes Taraborrelli does attribute, particularly a story about Janet giving Lee a check for $650,000, saying: “For any time I ever let you down, I’m very sorry. Maybe this small gift will make your life a little easier. I love you, Lee.”

Taraborrelli follows with: “We don’t know Lee’s reaction; she’s never discussed it and only she and Janet were in the room at the time the gift was presented.” So how is it that Taraborrelli, who was not in the room, can gives us Janet’s exact words?

Perhaps the quotes come secondhand from Taraborrelli’s main source for this book: James “Jamie” Auchincloss, the 71-year-old son of the aforementioned parents and the half-brother of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and Lee Radziwill, although Taraborrelli tells us: “[H]e never refers to Jackie and Lee as ‘halfs.’”

Full disclosure: I interviewed Jamie Auchincloss several times in 1975 when I was writing a biography of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. That book, Jackie Oh!, received attention because my interview with former Florida senator George Smathers was the first time a Kennedy intimate had gone on the record to discuss the president’s extra-marital affairs.

During our three-hour interview in his law office, Smathers also confirmed that Jacqueline Kennedy had received electroshock therapy for depression after losing her first child, Arabella, in 1956. Published 20 years later, my book also revealed for the first time the prefrontal lobotomy performed on the Kennedys’ eldest daughter, Rosemary, who was severely diminished by the surgery, and, as a result, spent the rest of her life in the care of the nuns at St. Coletta’s in Wisconsin.

While Jamie Auchincloss was not the source for those revelations, he did speak openly about his famous relatives and, unfortunately, he paid a price. Appearing on Charlie Rose’s local DC talk show a few years later, he said that Jackie stopped speaking to him after my book was published, much as she had with others whom she felt had shared too much personal information about the late president, including Ben Bradlee, who wrote Conversations with Kennedy, and Paul “Red” Fay, JFK’s Navy buddy, author of The Pleasure of His Company. When Fay sent his royalty check to the Kennedy Library, Jackie sent it back.

A few years ago, Jamie Auchincloss plunged from the height of being the 6-year-old page boy who carried the wedding train of his sister’s gown when she married John F. Kennedy to the scandal of being jailed at age 67 for the possession of child pornography. In 2009, he pleaded guilty to distributing what prosecutors called lewd and lascivious images, and was charged with two felony counts for encouraging child sexual abuse.

He spent Christmas 2010 in jail. Failing to cooperate with his court-ordered sex offender treatment program, he was sentenced to eight months in jail, serving just over half the time behind bars and the rest in home detention. He was put on probation for three years and ordered to stay away from children for the rest of his life and to register as a sex offender.

Taraborrelli writes that “this unfortunate turn in Jamie’s life in no way impacts his standing in history or his memories of growing up with his parents…and siblings…Or his brothers-in-law, Jack, Bobby, and Ted Kennedy. The times I spent with Jamie were memorable; I appreciate him so much. He also provided many photographs for this book.”

If you’re a reader who requires corroborated information and credible sourcing in your nonfiction, this book may give you pause. Then again, if your requirements are less stringent, you might enjoy the photographs.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

The Nine of Us: Growing Up Kennedy by Jean Kennedy Smith

by Kitty Kelley

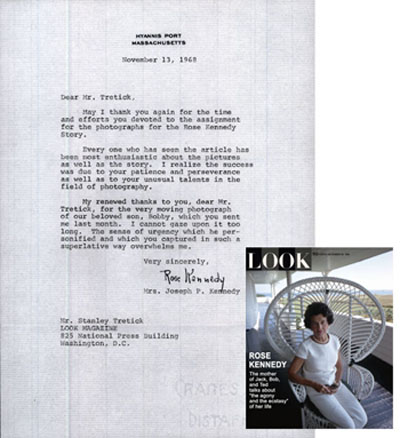

With hundreds of Kennedy books bending library shelves (I’ve written two: Jackie Oh! and Capturing Camelot: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the Kennedys), another seems like one more shamrock in Ireland — not needed for greening the landscape. But a memoir by 89-year-old Jean Kennedy Smith, the last surviving member of that storied family, might prove irresistible. Like one more chocolate in a binge. So why not?

With hundreds of Kennedy books bending library shelves (I’ve written two: Jackie Oh! and Capturing Camelot: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the Kennedys), another seems like one more shamrock in Ireland — not needed for greening the landscape. But a memoir by 89-year-old Jean Kennedy Smith, the last surviving member of that storied family, might prove irresistible. Like one more chocolate in a binge. So why not?

Caveat emptor: Don’t expect startling revelations or piercing insights. Reading The Nine of Us: Growing Up Kennedy is like sitting down with your great-grandmother to look at a scrapbook of old photographs taken with a Brownie camera loaded with Kodak film. A relic from a bygone era. Sweetly nostalgic.

You begin by already knowing the popular lore: “the nine” are Joe, Jack, Rosemary, Kathleen (aka “Kick”), Eunice, Pat, Jean, Bobby, and Teddy — the four sons and five daughters born to Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. and his wife, Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy, who lived to see the pinnacle of their most cherished aspirations when their second-born son, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, became the first Catholic president of the United States, and Irish Catholic at that.

This thin reverie of a book underscores the Irish Catholic heritage that produced the nine Kennedy children who grew up in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s pre-Vatican II era of Latin Masses every Sunday, meatless Fridays, grace before meals, and evening prayers.

Growing up in the 1950s, I, too, was taught by nuns to memorize, memorize, memorize — the Baltimore Catechism, not the world atlas. I can hardly locate Afghanistan on a map, but I’m still able to recite why God made me: “to know, love and serve him in this world and be happy with him in the next.” All by way of explaining why I might be more tolerant than most of Smith’s tendency to render verbatim the prayers and poems of her childhood as well as the Beatitudes from the Gospel of St. Matthew.

Smith recalls the visit Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, later Pope Pius XII, made to their home in Bronxville, where he sat on the sofa and held 4-year-old Teddy on his knee. Rose Kennedy later had a plaque made and mounted on the back of the sofa to commemorate the event. The author also relates her mother’s executive organizational skills in handling various childhood illnesses like measles, mumps, and chickenpox.

“Why spend the year cycling child after child through the flu…If one of us came down with a contagious illness, it simply made sense to her that the rest of us should come down with it too…So as soon as the doctor stepped from the room of a sibling to report an infectious disease, the rest of us were hustled inside by Mother to play…Within a week the sickness was out of the house for good.”

In previous books, Rose Kennedy has been dismissed as priggish, pious, and humorless, but her youngest daughter also shows her to be devoted to continual self-improvement for her children as well as herself. Even into her 90s, she was still trying to master a second foreign language. She lived to be 104.

At first, I assumed this slight book was ghostwritten but, as no other writer is named, perhaps not. Still, I agonized for whoever did the writing because the poor soul seemed to have no access to fresh material — no personal diaries, fulsome letters, or unpublished photographs.

Instead, the writer had to plunder the public record, cribbing a great deal from The Patriarch: The Remarkable Life and Turbulent Times of Joseph P. Kennedy by David Nasaw; Rose Kennedy’s memoir, Times to Remember; and Hostage to Fortune: The Letters of Joseph P. Kennedy, edited by Amanda Smith.

As the first journalist to reveal the pre-frontal lobotomy performed on Rosemary Kennedy, I have always been impressed by how the family used that tragedy to support their commitment to mental health. The Nine of Us does not ignore the experimental surgery, which Jean Kennedy Smith writes, “went tragically wrong…Rosemary lost most of her ability to walk and communicate,” adding that her father, who had sanctioned the procedure, “remained heartbroken over the tragic outcome…for the rest of his life.”

Yet Smith omits revealing her mother’s bitterness about what her father had done without consulting her or anyone else in the family. In her book The Fitzgeralds and the Kennedys, Doris Kearns Goodwin quotes Rose Kennedy at age 90: “He thought it would help [Rosemary]. But it made her go all the way back. It erased all those years of effort I had put into her. All along I had continued to believe that she could have lived her life as a Kennedy girl, just a little slower.”

Such a sin of omission — and there are many throughout the book — mars this memoir and keeps it from being more than superficial gloss.

Crossposted from Washington Independent Review of Books

Kitty Kelley on Book-TV

Kitty Kelley appeared on C-Span2’s Book-TV “In Depth” program on Sunday, Nov. 3, 2013, answering questions from host Peter Slen and from viewers for three hours. The show may be viewed online here.

Rose Kennedy: The Life and Times of a Political Matriarch

by Kitty Kelley

Anyone who has followed the Kennedys knows the bar is high for books on the subject. Having been inundated for the past 50 years with hundreds of biographies and memoirs and profiles about the spellbinding mystique of John Fitzgerald Kennedy, his family and his thousand days as the country’s first Irish-Catholic president, we expect each publication to bring something new and fresh to add to our understanding of the family that refashioned politics in the 20th century.

Anyone who has followed the Kennedys knows the bar is high for books on the subject. Having been inundated for the past 50 years with hundreds of biographies and memoirs and profiles about the spellbinding mystique of John Fitzgerald Kennedy, his family and his thousand days as the country’s first Irish-Catholic president, we expect each publication to bring something new and fresh to add to our understanding of the family that refashioned politics in the 20th century.

Serious historians (Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., William Manchester, James MacGregor Burns, Nigel Hamilton), journalists (Seymour Hersh, Jack Newfield, Warren Rogers), conspiracy theorists (Jim Garrison), commercial clip-and-pasters (Laurence Leamer, Christopher Anderson) and friends (Paul “Red” Fay, Benjamin C. Bradlee) have tried to capture the firefly magic of the Kennedys, while antagonists (Victor Lasky, Ralph de Taledano) have tried to puncture their myth.

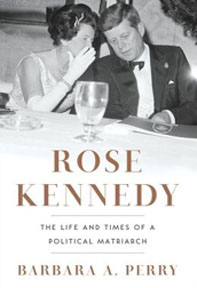

So now comes Barbara A. Perry with Rose Kennedy: The Life and Times of a Political Matriarch, who promises to deliver “the definitive biography” of the woman whose iron-fisted image-making produced the mystique that continues to endure. When the John F. Kennedy Library released the papers of the president’s mother (300 boxes) in 2006, Perry, a senior fellow in presidential oral history at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center in Charlottesville, was first in line, but, alas, Rose had no secrets beyond the few she revealed in her 1974 memoir, Times to Remember. As a biographer Perry was challenged. After six years of research and writing, she bowed to the obvious: With nothing new, she went for nuance. Her text is well written and her bibliography shows research, but there is no gold in the mine.

Her book cover, though, is perfect, absolutely perfect, because it captures the essence of Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy. The black-and-white photograph shows a woman who later died at the age of 104 after living her life by the black-and-white strictures of the Catholic Church, pre-Vatican II. Still glamorous at the age of 73, she is sitting next to the handsome president at a White House state dinner in 1963. She is acting as her son’s hostess because the first lady is away on one of her many vacations, similar to the ones Rose took for six to eight weeks at a time to get away from the clamor of her large family, and possibly, according to her biographer, as a means of Church-approved birth control. Rose is wearing the Molyneux gown she wore when she was 48 and her husband, Joseph P. Kennedy, was presented to the king and queen of England as the U.S. ambassador to the Court of St. James. That was the crowning glory of Rose’s life: To be accepted by British royalty was beyond the biggest dreams of a little girl from Dorchester, Mass.

Her book cover, though, is perfect, absolutely perfect, because it captures the essence of Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy. The black-and-white photograph shows a woman who later died at the age of 104 after living her life by the black-and-white strictures of the Catholic Church, pre-Vatican II. Still glamorous at the age of 73, she is sitting next to the handsome president at a White House state dinner in 1963. She is acting as her son’s hostess because the first lady is away on one of her many vacations, similar to the ones Rose took for six to eight weeks at a time to get away from the clamor of her large family, and possibly, according to her biographer, as a means of Church-approved birth control. Rose is wearing the Molyneux gown she wore when she was 48 and her husband, Joseph P. Kennedy, was presented to the king and queen of England as the U.S. ambassador to the Court of St. James. That was the crowning glory of Rose’s life: To be accepted by British royalty was beyond the biggest dreams of a little girl from Dorchester, Mass.

Bejeweled with two diamond clips in her hair, diamonds dripping from her ears, a triple strand of pearls the size of grapes circling her unlined neck and a bracelet of diamonds wrapped around her arm, which is encased in a long white kid-leather glove, Rose is whispering in her son’s ear.  Ever the canny pol, she covers her mouth so the photographer cannot catch a candid shot. (“I do not like candid pictures,” she said. “They are so unattractive.”)

Ever the canny pol, she covers her mouth so the photographer cannot catch a candid shot. (“I do not like candid pictures,” she said. “They are so unattractive.”)

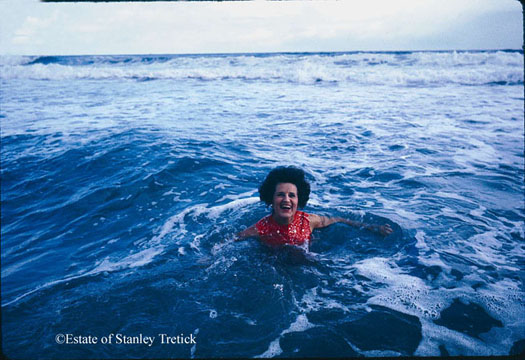

Oh, did I mention that the Molyneux gown was sleeveless? This is a detail Rose would want to have emphasized because she prided herself on her petite figure and frequently said that after having nine children she could still wear a size 8. Her frenetic exercise routine of swimming in the ocean every day, playing golf, walking miles, eating sparingly and rarely drinking had left her sleek and svelte with tanned, taut arms.

Appearances ruled Rose, and nothing mattered to her as much as how one looked — in person and in pictures. She made her children line up for daily inspections so she could see if their shoes were shined and their buttons attached. She saw each child as a reflection of herself and of the family name her husband was making famous on Wall Street and in Hollywood, so she strove for perfection, demanding it of herself and everyone around her. A martinet mother, she insisted her children brush their teeth three times a day and say their prayers every night. They were instructed to make meals on time or go without eating, and en route to the dining room they were required to check the bulletin board for the topics of current affairs that were to be discussed at dinner. Rose was the parent in charge of their childhood. When they became young adults her husband took over, but as one daughter said, “Dad gave us many lovely things but mother gave us our character.”

Despite her foibles and her husband’s philandering Rose relied on her strong religious faith to survive the worst tragedies of her life, and she managed to produce an extraordinary family of sons and daughters, who cared for each other, supported each other and remained close throughout their lives — and that is a mother’s finest legacy. Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy is an admirable subject but one that left her admiring biographer empty-handed.

Kitty Kelley’s seven biographies include Jackie Oh! (1978), the first book to reveal that the former first lady suffered from depression and was treated with electroshock therapy; it also reported for the first time that Rosemary Kennedy survived the mangled lobotomy her father had ordered in hopes of reversing her mental retardation. In 1988, People published Kelley’s story detailing President Kennedy’s affair with a woman who carried his messages to her other lover, mobster Sam Giancana.

Kitty Kelley’s seven biographies include Jackie Oh! (1978), the first book to reveal that the former first lady suffered from depression and was treated with electroshock therapy; it also reported for the first time that Rosemary Kennedy survived the mangled lobotomy her father had ordered in hopes of reversing her mental retardation. In 1988, People published Kelley’s story detailing President Kennedy’s affair with a woman who carried his messages to her other lover, mobster Sam Giancana.

Cross-posted with Washington Independent Review of Books.

Photos from Capturing Camelot ©Estate of Stanley Tretick, used with permission.

Gaithersburg Book Festival

On May 18, 2013 (Saturday), Kitty Kelley will be appearing at the Gaithersburg Book Festival, Gathersburg MD. Author presentation at James Michener Pavilion, 1:15 pm to 2:05 pm. Book signing (Capturing Camelot) 2:15 to 3:05 pm, Politics and Prose Signing Area. Click here for more details.

Camelot

by Kitty Kelley

John F. Kennedy continues to reign as the most popular president of the twentieth century, according to recent Gallup polls. (Richard Nixon and George W. Bush remain the most unpopular). Most historians agree that Abraham Lincoln was the most important man to ever occupy the White House because he abolished slavery and kept the states united through a bloody civil war. Yet for most Americans, Kennedy, whose presidential accomplishments were slight, continues to glisten like a shamrock after a spring rain.

For those alive in 1963 this month casts a shadow of sadness as we recall where we were on November 22 when we heard about the president’s assassination. We remember the weekend binge of television coverage — the stalwart widow in her black veil, the riderless horse, the little boy’s salute to his father’s coffin and the eternal flame, which draws over 500,000 visitors a year to Arlington National Cemetery.

Beginning last year we mark the 50th anniversary of the Kennedy administration — the thousand days which J.F.K. defined as the New Frontier, a time when he said the torch was passed to a new generation. We were told to ask not what our country could do for us but what we could do for our country, and he showed us how by establishing the Peace Corps so Americans could do something positive and lasting. Since 1961 more than 210,000 volunteers have served in 139 countries.

Yet it is for something far less tangible that John F. Kennedy continues to be revered. Elected fifteen years after the end of WWII, he captured the spirit of those times. He radiated the excitement of change and the optimism of expectation. He broke the barriers of religious bigotry by becoming the first Catholic to be elected president, thereby making us believe that anything was possible, even sending a man to the moon and back within a decade. He moved further than his predecessors on civil rights by declaring that equality under the law was a moral issue “as old as the Scriptures and as clear as the Constitution.” He believed in horizons without limits. “No problem of human destiny is beyond human beings,” he said, speaking about the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty which was signed in August 1963.

Yet it is for something far less tangible that John F. Kennedy continues to be revered. Elected fifteen years after the end of WWII, he captured the spirit of those times. He radiated the excitement of change and the optimism of expectation. He broke the barriers of religious bigotry by becoming the first Catholic to be elected president, thereby making us believe that anything was possible, even sending a man to the moon and back within a decade. He moved further than his predecessors on civil rights by declaring that equality under the law was a moral issue “as old as the Scriptures and as clear as the Constitution.” He believed in horizons without limits. “No problem of human destiny is beyond human beings,” he said, speaking about the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty which was signed in August 1963.

John F. Kennedy brought style and charisma to the White House and a first family that captivated the country: a handsome, witty president, an elegant first lady, and two adorable young children. While his image was later tarnished by revelations of marital infidelity and reckless behavior, polls show that he still holds the public in thrall. Herbert Parmet, one of his many biographers, claimed he was nothing but glamour and gloss, and dismissed him as an “interim president who had promised but not performed.” Yet there is no way to diminish the nation’s nostalgia for this man who was felled in his prime, and became an enduring legend. No other president has left a larger footprint on his country than John F. Kennedy, who to date is honored by 149 institutions which carry his name — schools, hospitals, clinics, concert halls, arts centers and an international airport, proving perhaps that promise is as inspiring as performance.

John F. Kennedy brought style and charisma to the White House and a first family that captivated the country: a handsome, witty president, an elegant first lady, and two adorable young children. While his image was later tarnished by revelations of marital infidelity and reckless behavior, polls show that he still holds the public in thrall. Herbert Parmet, one of his many biographers, claimed he was nothing but glamour and gloss, and dismissed him as an “interim president who had promised but not performed.” Yet there is no way to diminish the nation’s nostalgia for this man who was felled in his prime, and became an enduring legend. No other president has left a larger footprint on his country than John F. Kennedy, who to date is honored by 149 institutions which carry his name — schools, hospitals, clinics, concert halls, arts centers and an international airport, proving perhaps that promise is as inspiring as performance.

Photos © Estate of Stanley Tretick, LLC, used with permission.

Cross-posted from Huffington Post

Capturing Camelot on Morning Express

Kitty Kelley appeared on HLN Morning Express to talk about Capturing Camelot on November 25, 2012.

Capturing Camelot on Starting Point

Kitty Kelley appeared on Starting Point on November 14, 2012 to talk about Capturing Camelot.

Capturing Camelot on Jansing & Co.

Kitty Kelley appeared on Jansing & Co. on November 14, 2012.

Capturing Camelot on the Today Show

Kitty Kelley appeared on the Today Show to talk about Capturing Camelot.

November 13, 2012

The Today Show also posted a slide show of photos from the book.