General

John Lewis

by Kitty Kelley

A masterful biography is like a shooting star. It’s a celestial phenomenon that lights up the night sky and bestows a sense of wonder and excitement. Such a sensation occurs when the stars align and match a subject of worth with an estimable writer. That kind of luminous pairing occurs in David Greenberg’s John Lewis: A Life, the first major biography of the man Martin Luther King Jr. called “the boy from Troy.”

A masterful biography is like a shooting star. It’s a celestial phenomenon that lights up the night sky and bestows a sense of wonder and excitement. Such a sensation occurs when the stars align and match a subject of worth with an estimable writer. That kind of luminous pairing occurs in David Greenberg’s John Lewis: A Life, the first major biography of the man Martin Luther King Jr. called “the boy from Troy.”

Growing up as the third of 10 children in Alabama’s abysmal poverty, John Robert Lewis (1940-2020) aspired to be a preacher, a challenge for a child with a heavy rural accent and a speech impediment. At the age of 5, he practiced preaching to the chickens on his family’s farm in Pike County, on the outskirts of Troy. His elementary school education was at Dunn’s Chapel, built and funded by Julius Rosenwald, the Sears, Roebuck heir, who, with Booker T. Washington, created 5,000 schools for Black children around the South. After the Bible, Washington’s Up from Slavery became young John’s favorite book.

Born into segregation, Lewis sat in the “colored only” balcony to watch movies, and he drank Cokes standing outside the drugstore, while his white peers sat inside at the counter. He finally stopped going to the Pike County fair because he could only go on “colored day.”

Lewis became the first in his family to attend college. After being rejected by Troy University in 1957 due to segregation, he enrolled at American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, supposedly the “most liberal city” in the Confederacy. He later transferred to nearby Fisk University, where he earned his degree.

As a college sophomore, Lewis became transfixed by the preaching of nonviolence by King, Mahatma Gandhi, and members of the Social Gospel movement. Unshakeable in his faith that “God would never allow his children to be punished for doing the right thing,” the young man consecrated himself to the Civil Rights Movement and began organizing sit-ins at segregated lunch counters, stand-ins at segregated department stores, and swim-ins at segregated pools.

The youngest speaker at 1963’s March on Washington, Lewis was one of the original Freedom Riders to integrate seating on public buses; he was frequently bloodied and beaten unconscious. He was arrested and jailed dozens of times for demonstrating throughout the South, and once spent 40 days in the Mississippi State Penitentiary. Yet he never struck back, adhering always to Gandhi’s nonviolence creed. “We were determined not to let any act of violence keep us from our goal,” said the young man once so terrified of thunder and lightning that he’d hide in the family’s steamer trunk whenever it stormed.

Greenberg, a prize-winning professor of U.S. history and journalism at Rutgers, divides his spectacular biography of the Civil Rights icon into two parts: Protest (1940-1968) and Politics (1969-2020). One of his most arresting chapters, “John vs. Julian,” mimics Aesop’s fable of the tortoise and the hare: Lewis, the slow-moving tortoise, went up against Julian Bond, the fast-paced hare, in a 1986 campaign to be the Democratic candidate for Georgia’s 5th District seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. The campaign defined their professional futures while destroying their once-close friendship.

The contrast was stark: Lewis in shiny, rumpled suits and worn-out shoes, alongside Bond in custom-made blazers and tasseled loafers. Smooth, suave, and light-skinned, Bond, an “incorrigible ladies’ man,” was hiding a heavy cocaine habit, which Lewis exposed during a debate by challenging him to take a drug test. Bond refused.

Lewis pushed. “Can you tell us why you will not take the test,” he said, “so that people will know that you are not on drugs?”

Bond responded that he was not on drugs, and the moderator asked Lewis if he was accusing his opponent of illegal drug use.

“No,” said Lewis, a bit disingenuously. “I do not suspect that he is on drugs, I just feel like he should take the test to clear his name and remove public doubt. People need to know.”

Bond was incensed. “Why did I have to wait twenty-five years to find out what you really thought of me?”

Lewis replied, “Julian, my friend, this campaign is not a referendum on friendship. This is not a referendum on the past. This is a referendum on the future of our city, the future of our country.”

Supported by the white vote in Atlanta, Lewis won the run-off 52-48, and later, the election. “We will shake hands,” he told the press. “The wounds will heal.”

The wounds remained. Bond died in 2015 at age 75, and Lewis was not invited to the funeral.

The most compelling aspect of this work is its in-depth research, including 250 interviews, which has allowed Greenberg to paint a vivid portrait of the man heralded as “the conscience of congress.” The professor’s academic credentials (summa cum laude at Yale; a Ph.D. from Columbia), combined with his journalistic talent (he has bylines in Politico, the New Yorker, the Atlantic, and the New York Times), have brought forth this captivating biography of a hero who cried easily, laughed often, and never lost faith in “the beloved community,” where all God’s children, particularly those who got into “good trouble,” would be blessed.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Ninth Street Women

by Kitty Kelley

Curling up with a hefty book of almost 1,000 pages dense with footnotes, endnotes, acknowledgements, an index, and a bibliography is like cuddling a St. Bernard: It’s a challenging prospect. Yet Mary Gabriel’s behemoth Ninth Street Women: Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler: Five Painters and the Movement that Changed Modern Art rewards in almost every chapter.

Curling up with a hefty book of almost 1,000 pages dense with footnotes, endnotes, acknowledgements, an index, and a bibliography is like cuddling a St. Bernard: It’s a challenging prospect. Yet Mary Gabriel’s behemoth Ninth Street Women: Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler: Five Painters and the Movement that Changed Modern Art rewards in almost every chapter.

Gabriel has written a massive homage to the women who barged through “men only” barriers to help establish Abstract Expressionism in America, a movement (1937-1957) once defined solely by male artists like Jackson (“Jack the Dripper”) Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, and Robert Rauschenberg.

Discrimination against women artists was so pervasive at the time that art historians claim Grace Hartigan exhibited her work under the name George Hartigan until 1953, when she was finally given her first show. A raging feminist and the first female artist to make money, Hartigan denied the charge. “It never entered my head,” she said. Elaine de Kooning also rebuked being characterized as a woman artist:

“To be put in any category not defined by one’s work is to be falsified.”

Readers will be grateful that the author defines Abstract Expressionism through the women painters who resisted being characterized as such but represented with their husbands and lovers, “too often fueled by alcohol and dizzying infidelities,” the miraculous movement of 20th-century art in America.

Lee Krasner, who married Pollock, signed her paintings with initials only so no one would identify her work as having been done by a

Seated from left: Elaine de Kooning, Lee Krasner, Willem de Kooning, and Jackson Pollock at the Museum of Modern Art, ca. 1950

woman. Early in Krasner’s career, she took lessons from the esteemed painter Hans Hofmann, who stood before her easel one day in wonder. “This is so good you would never know it was done by a woman,” he said. Krasner later focused on helping her husband gain recognition because she believed that he had “much more to give with his art than I do with mine.”

Elaine de Kooning, a painter in her own right, frequently slept with renowned art critics and gallery owners in order to promote her husband’s work. One male artist of the era is quoted as saying, “The fifties was a boys club, but some of the women painted almost as well as the boys so we patted them on the ass twice and said keep going.” Elaine de Kooning collected lots of pats.

The book, a bohemian saga, divides between the first wave of female artists — Krasner and de Kooning, scramblers who lived in the shadow of their famous spouses and only came into their own as painters later on — and the second wave of more successful figures like Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler.

Joan Mitchell Helen Frankenthaler and Grace Hartigan in 1957.

Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler, and Grace Hartigan in 1957.Photograph by Burt Glinn / Magnum

All of these women, with the exception of Frankenthaler, gravitated to the grittiest parts of Greenwich Village around Ninth Street, where they toiled in cold-water flats with no heating or plumbing but surrounded by great wall space where they could spread their canvases. Gabriel describes Frankenthaler as the daughter of a New York Supreme Court judge and a graduate of Bennington College in Vermont, then the most progressive and expensive women’s school in the U.S.:

“She was a woman of enormous self-confidence who never wasted her time with anything but the best.”

The most tempestuous was Mitchell, raised by prosperous parents in Chicago who arranged for her to go to Paris to meet Alice B. Toklas, the life partner of Gertrude Stein, and Sylvia Beach, who owned Shakespeare and Company, the French bookstore that published James Joyce and sold copies of Ernest Hemingway’s first book. When Mitchell married Barney Rosset, the union made history: Rosset owned Grove Press, which published Samuel Beckett, Pablo Neruda, Tom Stoppard, Henry Miller, and D.H. Lawrence. Mitchell, the author maintains, “was one of the greatest artists the U.S. has ever produced.”

The book sweeps from erudite scholarship to gritty gossip as it presents the panorama of American art history from the Depression and World War II through McCarthyism and the Red Scare, all of which affected the majestic talents of the “Ninth Street Women.” Like a St. Bernard, that majestic alpine dog, it will save you from avalanches of boredom and ennui and provide a vicarious plunge into the messy lives and mesmerizing genius of American Abstract Expressionism. You’ll emerge gobsmacked and gratified.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

When Women Ran Fifth Avenue

by Kitty Kelley

Given that women are the biggest buyers of books in America, and that the country also boasts the largest apparel market in the world ($312.4 billion from 1992 to 2022), the combination of a book about women in fashion is bound to be a bestseller for Julie Satow, who ingeniously spotlights the three female moguls who ruled Fifth Avenue fashion in the 20th century.

Given that women are the biggest buyers of books in America, and that the country also boasts the largest apparel market in the world ($312.4 billion from 1992 to 2022), the combination of a book about women in fashion is bound to be a bestseller for Julie Satow, who ingeniously spotlights the three female moguls who ruled Fifth Avenue fashion in the 20th century.

With style and sass, Satow tells the story of the trio who revolutionized retail at Bonwit Teller, Lord &Taylor, and Henri Bendel. Each of those plate-glass palaces, late and lamented, reigned as cathedrals to the carriage trade. While all three were purchased by men, each blossomed into profit and prestige under women, and Satow unspools their stories of success with polish and panache, writing of an era in which department stores were consumer wonderlands and rich emporiums of luxurious goods.

Satow begins When Women Ran Fifth Avenue at the height of the Depression, with Hortense Odlum arriving at Bonwit Teller wrapped in fur as she steps from her chauffeured limousine to enter the Art Deco skyscraper her husband, Floyd, now owned as part of Atlas Corporation. Unbeknownst to Hortense, 41, her husband had fallen in love with the young woman behind the perfume counter, but he decided his wife, who’d never worked but always shopped, could transform Bonwit’s, then bordering on bankruptcy. Said Floyd:

“Just take a look and tell me what you think…Figure out why women don’t shop there anymore.”

Hortense Odlum

Hortense accepted the challenge. She took a look, made a few suggestions, and, thinking the corner office and title of president would only be temporary, began rearranging the boutiques and salons, painting and redecorating every department and, most importantly, relating to customers as “high class, but not high hat.” The 26-year-old behind the perfume counter ended up marrying Floyd, who financed her career as a pilot; Hortense, meanwhile, became the first female titan on Fifth Avenue, a position she held for six years before she abruptly retired, embittered by the price she’d paid for her professional success. “I worked like a Trojan. But I never intended to stay,” she remarked. “I’m out now and the whole thing leaves me cold.”

Dorothy Shaver

The real Trojan, who thrived on the 24/7 work and the pressure of retail business, was Dorothy Shaver of Mena,

Arkansas, who devoted her life to the job from 1921 until the day she died in 1959. Shaver became president of Lord & Taylor and, writes Satow, “Fifth Avenue’s First Lady.” By the time she died, Shaver, who never married and lived with her sister, had rocketed store sales to $100 million a year and was revered throughout society. Her death at the age of 66 made the front page of the New York Times, which hailed the “First woman ever elected to head a large retail corporation when she became president of Lord & Taylor.” Such was her standing that the paper’s publisher, Arthur Hays Sulzberger, wrote to Dorothy’s sister: “Terribly distressed to hear of your loss.” Gov. Nelson Rockefeller, former U.S. president Herbert Hoover, and Vice President Richard Nixon also sent their condolences.

By this time, Geraldine Stutz was reigning over the exclusive boutique of Henri Bendel and dispatching buyers

to the side streets of Paris to purchase garments only from small-scale designers and only in small sizes. Given her phobia about weight, Stutz stocked sizes two, four, and six, figuring that anyone larger should shop at Macy’s. Stutz decreed Henri Bendel would be all about style. “I want our own stuff, the way that we want it.” Her mantra:

“Fashion says, ‘Me, too,’ while style says ‘Only me.’”

Geraldine Stutz

As a connoisseur of style, Stutz hired a uniformed butler to greet Bendel’s clientele, opening doors, supplying umbrellas, and hailing cabs for the privileged likes of Gloria Vanderbilt, Cher, Barbra Streisand, and Lee Radziwill. In addition to providing European fashion for elite shoppers, Stutz converted Bendel’s sixth level into “the beauty floor,” with a hair salon, cosmetic counter, and Pilates studio for her slim clientele. In addition, she opened a sportswear department, most appropriately called Cachet. It was not to last long.

The demise of these luxury stores started at the end of the 20th century, when Bonwit Teller closed and the building at 56th and Fifth Avenue was bulldozed by Donald J. Trump, who erected Trump Tower, 58 stories of shining brass and, according to the BBC, “enough pink marble to make Liberace blush.” Trump draped his doormen in gold braid and dangling epaulets like “The Pirates of Penzance” and ushered in the Gordon Gekko era of “greed is good.”

Fifth Avenue elegance made its last gasp in 2019, when Henri Bendel folded just weeks before Lord & Taylor, America’s oldest department store, collapsed and emerged from bankruptcy as a website. By then, the sun had set on Satow’s “Glamour and Power at the Dawn of American Fashion,” but her recollections of Hortense’s heyday, Dorothy’s legendary run, and Geraldine’s Street of Shops make for a wistful look at retail’s most romantic era.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

The Indispensable Right

by Kitty Kelley

Jonathan Turley road-tested an idea last year with a 45-page article entitled “The Right to Rage: Free Speech and Rage Rhetoric in American Political Discourse” for the Georgetown Journal of Law & Public Policy. Now, Turley, the J.B. and Maurice C. Shapiro Professor of Public Interest Law at George Washington University Law School, has expanded his “rage” thesis into The Indispensable Right: Free Speech in an Age of Rage.

Jonathan Turley road-tested an idea last year with a 45-page article entitled “The Right to Rage: Free Speech and Rage Rhetoric in American Political Discourse” for the Georgetown Journal of Law & Public Policy. Now, Turley, the J.B. and Maurice C. Shapiro Professor of Public Interest Law at George Washington University Law School, has expanded his “rage” thesis into The Indispensable Right: Free Speech in an Age of Rage.

He garnered blurbs for his new book from friends like former attorney general William P. Barr (“a robust reexamination and defense of free speech as a right”), conservative columnist George F. Will (“This efficient volume is packed with indispensable information”), and CNN host Michael Smerconish (“a master class on the unvarnished history of free speech in America”).

The professor posits that we’re living in one of the most anti-free-speech periods in history; as examples, he cites the divisiveness of racial discrimination, police abuse, climate change, and gender equality. “Any and all of these issues can provoke public anger and mob rage,” he writes.

Turley’s book promises “a timely, revelatory look at freedom of speech.” Unfortunately, he doesn’t deliver on that promise and breaks no new ground in exploring the most basic right of all Americans. He concedes as much in his acknowledgements. “This is not the first book on free speech. It is not even the hundredth…[T]here are masterful prior works.” Here, he cites the books of three professors like himself but omits the gold standards of the genre: The Soul of the First Amendment and Speaking Freely: Trials of the First Amendment by Floyd Abrams and Freedom for the Thought That We Hate: A Biography of the First Amendment by Anthony Lewis, who also wrote Gideon’s Trumpet and Make No Law: the Sullivan Case and the First Amendment.

There’s always room on the shelf for a riveting new tome on the First Amendment, for it is the fundamental right that protects all others. Yet, while Turley climbs the tower, he doesn’t ring the bell. Rather, the professor seems to have summoned “the many law students…who have assisted me in decades of research and writing on the theories and cases discussed in this book” and then cedes control to the inmates. In other words, the orchestra conductor drops his baton and lets the timbales and tom-toms take over. The concert makes noise but hardly inspires.

Turley credits Justice Louis Brandeis for “the indispensable right” of his title but claims subtitle credit for himself and his students, who march readers through all the ages of fury in sections that include, among many others: “The Boston Tea Party and America’s Birth in Rage”; “The Whiskey Rebellion and ‘Hamilton’s Insurrection’”; “Adams and the Return of ‘The Monster’”; “Jefferson and The Wasp”; “Jackson and the ‘Lurking Traitors’ Among Us”; Lincoln and the Copperheads; Comstock and the Obscenity of Dissent; “The Bund and the Biddle: Sedition in World War II”; “Days of Rage: Race, Rhetoric, and Rebellion in the 1960s”; “Antifa, MAGA, and the Age of Rage”; and “January 6th and the Revival of American Sedition.”

Turley has evolved from a liberal Democrat who voted for Bill Clinton in 1992, Ralph Nader in 1996, and Barack Obama in 2008 to an unbending critic of Obama and his “sin eater,” Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr. Turley went on to support Neil Gorsuch for confirmation to the U.S. Supreme Court and publicly promote his friend Bill Barr as Donald Trump’s attorney general, while bashing the Bidens for alleged influence-peddling. In 2022, Slate took notice of this political evolution and asked, “What Happened to Jonathan Turley, Really?”

The online magazine concluded that the man who “was once a serious and respected legal scholar” has devolved into a paid contributor for Fox News who presents “himself as a kind of Alan Dershowitz with table manners.”

Turley is not immune to such slights. At the end of The Indispensable Right, he writes, “I hope that this book will explain my own long and at times unpopular fight for free speech rights.” That plaintive wish calls to mind the Oval Office address Aaron Sorkin penned for Michael Douglas in “The American President”:

“We’ve got serious problems, and we need serious people…If you want to talk about character and American values, fine. Just tell me where and when, and I’ll show up.”

One hopes that Jonathan Turley would show up, too, if only to defend his treatise on free speech.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

The Loves of Theodore Roosevelt

by Kitty Kelley

The huge granite sculpture startles tourists. Looming like a ferocious behemoth — intimidating, almost frightening — the 17-foot giant dominates the National Park Service space on the western bank of the Potomac River. If not for the “Welcome to Theodore Roosevelt Island” sign, one might assume the black stone colossus — his right hand raised as if to acknowledge the homage of marauding troops — towering above the cement-slab plaza was some sort of warring commissar. Yet spiraling out from the fearsome statue are 88 forested acres of majestic trees and woodland paths, designed by Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., paying tribute to the conservationist and naturalist who was the 26th president of the United States.

The huge granite sculpture startles tourists. Looming like a ferocious behemoth — intimidating, almost frightening — the 17-foot giant dominates the National Park Service space on the western bank of the Potomac River. If not for the “Welcome to Theodore Roosevelt Island” sign, one might assume the black stone colossus — his right hand raised as if to acknowledge the homage of marauding troops — towering above the cement-slab plaza was some sort of warring commissar. Yet spiraling out from the fearsome statue are 88 forested acres of majestic trees and woodland paths, designed by Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., paying tribute to the conservationist and naturalist who was the 26th president of the United States.

“T.R.,” or “Colonel Roosevelt,” as he preferred, could not abide being called “Teddy.” He believed that “physical bravery was the highest virtue and war the ultimate test of bravery,” according to one of his biographers, and all historians emphasize Roosevelt’s “warrior persona” and his “speak softly and carry a big stick” ideology. As president, he destroyed the portrait of himself by Théobald Chartran because he felt it made him look weak, like a “meek kitten.”

Mother Martha “Mittie” Roosevelt; Wife Alice Roosevelt

Declaring himself “as fit as a bull moose,” T.R. gloried in fighting wars and shooting and killing wildlife. He donated several specimens bagged on hunting trips, including a snowy white owl, to the American Museum of Natural History, which his father helped establish in 1869. In fact, it’s hard to think of a more testosterone-charged president than Theodore Roosevelt, the “Rough Rider” who championed the “bully pulpit,” launched construction of the Panama Canal, and brokered the end of the Russo-Japanese War, for which he won the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize, the first American to be so honored.

There are more than three-dozen biographies in print about Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919), including his own memoir — one of the 47 books he wrote, including The Rough Riders, The Strenuous Life, African Game Trails, and Theodore Roosevelt’s Letter to His Children. Now comes another biography, The Loves of Theodore Roosevelt: The Women Who Created a President by Edward F. O’Keefe, CEO of the Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library Foundation, the group spearheading the building of T.R.’s library, currently under construction in the Badlands of North Dakota.

O’Keefe’s first book, The Loves of Theodore Roosevelt presents an astonishing thesis about the man whose rugged visage is carved on Mount Rushmore and who may be regarded as the exemplar of the XY chromosome. This biography proffers that “the most masculine president in the American memory was, in fact, the product of largely unsung and certainly extraordinary women.”

Sister Anna “Bamie” Roosevelt Cowles

The author argues that five women provided the ballast of Roosevelt’s life and were the source of his greatest

Sister Corinne Roosevelt Robinson

accomplishments: his mother, Mittie; his sisters Bamie and Conie; and his two wives, Alice, who died after giving birth to their first child, and Edith, his second wife, with whom he had five more children. These women were “the team who would guide his future for the next several decades and craft his legacy.” Indeed, O’Keefe writes, the two greatest mistakes T.R. made were when he acted on his own without the counsel of his female consortium.

“The biggest blunder of his political life was a pledge he would not seek what he called a ‘third’ term” as president. As vice president to William McKinley, T.R. assumed the presidency in 1901 when McKinley was assassinated and, in 1904, won election on his own. Then, without consulting his closest confidantes — his wife and his sisters — the newly elected president announced that he would not seek re-election at the end of his first term, a decision he sorely regretted.

Roosevelt’s second blunder, again made without consulting his wife and sisters, was to announce William Howard Taft as his successor. Later, T.R. became so distressed by his lack of judgment that he founded the Progressive Party, popularly known as the Bull Moose Party, and ran, unsuccessfully, on a third-party ticket against Taft.

Wife Edith Roosevelt

In researching Roosevelt’s life at Sagamore Hill National Historic Site in Oyster Bay, New York, O’Keefe discovered something that had eluded previous biographers: a small, blue velvet box, circa 1880, with a silk-covered divider that contained a secret keepsake — a photograph of Alice Hathaway Lee, T.R.’s first wife, and 14 inches of her wavy, dark, golden blond hair. On top of it was a note in Roosevelt’s own hand, reading: “The hair of my sweet wife, Alice, cut after death.”

Roosevelt has been described as an opportunist, exhibitionist, and imperialist. But O’Keefe presents a perceptive and persuasive argument that adds a sensitive dimension to the masculine persona of Theodore Roosevelt as a man indebted to the women in his life, proving, as 19th-century poet William Ross Wallace wrote, “The hand that rocks the cradle is the hand that rules the world.”

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Thinkin’ in the Bardo

by Kitty Kelley

George Saunders did not want his tombstone to read, “Here lies a guy who never did what he wanted to do.” So, in 2017, at the age of 59, having mastered the art of the dystopian short story, Saunders secretly began writing his first novel. Four years later, he burst into the literary stratosphere with Lincoln in the Bardo, which earned him the Man Booker Prize. Colson Whitehead, already in that stratosphere, called Saunders’ book “a luminous feat of generosity and humanism.”

In The Tibetan Book of the Dead, the bardo is the interim space between life and afterlife where spirits who’ve not yet reconciled their deaths must remain until they resolve lingering issues with their lives and can proceed to their next incarnation.

“I was raised Catholic, where purgatory is like the DMV,” said Saunders, now a practicing Buddhist, who made his literary bona fides as a comic sci-fi writer and published frequently in the New Yorker. During that time, he was named a MacArthur Fellow (aka a “Genius Grant” recipient), garnered a Guggenheim Fellowship, and won the PEN/Malamud Award for Excellence in the Short Story. In addition, he became a full professor at Syracuse University, where he teaches in the MFA program.

Those prestigious awards seem to hang lightly on Saunders, whose scruffy beard and rumpled jeans make him look a bit impish, rather like a choirboy gone rogue. Politically, he admits to being a liberal (“left of Gandhi, actually”) and acts as comfortable behind a lectern as he is conversing with Stephen Colbert on late-night television.

Saunders recently returned to Washington, DC, to speak at the Library of Congress, where he’d received its 2023 prize for best American fiction. The following day, he led a small troupe of admirers to the marble crypt in Oak Hill Cemetery where Abraham Lincoln’s 11-year-old son, Willie, who died of typhoid fever on February 20, 1862, once lay. Willie became pivotal among the 166 characters Saunders created in his prizewinning novel.

Saunders recently returned to Washington, DC, to speak at the Library of Congress, where he’d received its 2023 prize for best American fiction. The following day, he led a small troupe of admirers to the marble crypt in Oak Hill Cemetery where Abraham Lincoln’s 11-year-old son, Willie, who died of typhoid fever on February 20, 1862, once lay. Willie became pivotal among the 166 characters Saunders created in his prizewinning novel.

Leading the group through the 150-year-old cemetery at the top of Georgetown, Saunders related how the grief-ravaged president rode his horse late at night from the White House to sit in the gated crypt belonging to William Thomas Carroll, where he held the casket of his beloved son. The Carroll mausoleum is the most visited gravesite in the cemetery. In addition to sharing his family’s crypt with the president, Carroll, clerk of the U.S. Supreme Court, also loaned the commander-in-chief his family Bible to be sworn in on as president in 1861. President-elect Barack Obama used that same Bible for his own 2009 swearing-in.

“The thing about a place like Oak Hill…walking through it always makes me feel more alive and more urgent about…whatever it is I’m supposed to be doing down here,” Saunders wrote on his Substack account of the visit. “There’s no ‘we’ and no ‘them.’ There’s just life and then that grand waterfall we all will have to go over.”

During the tour, the cemetery archivist presented Saunders with a circa-1862 key of the type Lincoln would have used to gain entry to the cemetery. (“Do I love this kind of thing?” Saunders wrote later. “You know I do.”) He recalled being transported the first time he visited the gravesite:

“Wow. This really happened. Lincoln, really, for sure, stood here…somehow that made me feel I could and must write the book.”

The publication of Lincoln in the Bardo has bound Saunders to the Georgetown burial ground in ways he never imagined while writing. In addition to the novel’s prizes and plaudits — which include the 2018 Audie Award for audiobook of the year — the Metropolitan Opera has commissioned Missy Mazzoli, an American composer, to create an opera based on Saunders’ book to debut in 2026. A movie is also in the works. “This connects me forever to Oak Hill,” said Saunders.

Later that evening, he spoke in the cemetery’s Renwick Chapel, where Willie’s funeral was held. Standing in front of the huge stained-glass window featuring a giant angel uplifted by iridescent wings, the professor talked about the creative process and how he met the challenge of conjuring spirits to communicate with the anguished Lincoln, who finds the strength amid the graveyard’s clamoring lost souls to rise above his personal sorrow and lead the country through the Civil War. Saunders believes it was that graveside evolution within Lincoln that enabled him to write the Emancipation Proclamation.

“When a writer has a problem, the reader feels it, and then, when the writer identifies and addresses that problem — presto — this feels like originality and innovation,” he told the chapel crowd.

Some writers never get to “presto,” but for those who do, exhilaration awaits. In conveying the magic of creativity, Saunders echoed William Faulkner’s 1950 Nobel Prize address about the writer’s responsibility to create “out of the materials of the human spirit something which did not exist before.” George Saunders did exactly that with Lincoln in the Bardo.

Photo by Laura Thoms

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

An Unfinished Love Story

by Kitty Kelley

The Bible’s “Parable of the Talents” (Matthew 25:14-30) instructs on how to live a worthwhile life. In that story, a master leaves his mansion to take a long trip and entrusts his silver to his servants in accord with their talents. To one, he gives five bags, to another, two bags, and to the last servant, one bag.

The Bible’s “Parable of the Talents” (Matthew 25:14-30) instructs on how to live a worthwhile life. In that story, a master leaves his mansion to take a long trip and entrusts his silver to his servants in accord with their talents. To one, he gives five bags, to another, two bags, and to the last servant, one bag.

Many months later, the master returns and asks for an accounting. The servant given five bags has invested wisely and doubled his silver, as has the second servant. The master is pleased and praises each fulsomely. The third servant says he was afraid of losing his bag, so he buried it in the ground. The master becomes irate and chastises him as wicked and lazy: “To those who use well what they are given they will have abundance in life. For those who do not, the little they have will be taken away, and they will be thrown into darkness where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.”

Such a master would embrace Doris Kearns Goodwin, for she has used well what she’s been given. Gathering her late husband’s manifold talents, she’s added her own, and burnished both, to write a glorious new memoir, An Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960s.

Richard Goodwin (1931-2018) and Doris Kearns married in 1975 in a wedding the New York Times described as blessed with “New Yorkian style, Washington power and Boston brains.” Each had established strong political allegiances beforehand, which, she admits, frequently caused marital combustion, particularly when they began working on this book, which started out being Richard’s life story. He’d decided, at the age of 80, that he was ready to tackle the 350 boxes of speeches, articles, journals, letters, and diaries he’d saved and start writing.

He asked his wife for help — “jog my memory, ask me questions” — so they hired a researcher and began what Goodwin calls their last great adventure together, which lasted until Richard, suffering from cancer, clasped her hand, declared her “a wonder,” and passed into a new frontier. After his death, she spent many years conjoining his story with her own to produce this rich and riveting chronicle of the turbulent 1960s.

Long before they wed, Richard was a wunderkind — a prodigy who coined memorable phrases that included the legendary title of Lyndon  Johnson’s legislative agenda, “The Great Society.” However, before he accepted the job in the LBJ White House, Richard sought permission from Robert F. Kennedy, and then wrote a “Dear Jackie” letter, assuring JFK’s widow, “We will all always be Kennedy men.” He remained totally committed to the Kennedys, having crafted speeches for the president and both of his politician brothers, weaving words of poetry into policy.

Johnson’s legislative agenda, “The Great Society.” However, before he accepted the job in the LBJ White House, Richard sought permission from Robert F. Kennedy, and then wrote a “Dear Jackie” letter, assuring JFK’s widow, “We will all always be Kennedy men.” He remained totally committed to the Kennedys, having crafted speeches for the president and both of his politician brothers, weaving words of poetry into policy.

Goodwin, on the other hand, was fiercely loyal to President Johnson, having worked closely with him in the White House and, later, on his memoir. She admits being troubled by many passages in her husband’s diaries, particularly those dealing with Bobby Kennedy’s animosity toward Johnson and his insensitivity to “the mammoth problems that beset the new president and the country at large.” She became irate when she found a memo her husband had written quoting RFK about the choice of a running mate on LBJ’s 1964 presidential ticket: “When the time comes we’ll tell him who we want for vice-president.”

“Who does he think he is?” she asked her husband, who explained Kennedy was simply venting grief over his brother’s assassination. “It’s the arrogance of ‘we’ll tell him who we want’ that sticks in my craw.”

The couple’s clash of political loyalties continued “provoking tension,” as Goodwin insisted that civil rights, medical care for the aged, federal aid for education, and an overhaul of immigration only became law under President Johnson, while Richard countered that President Kennedy’s leadership set the tone and spirit of the decade. “Both of us looked back upon these years with a decided bias,” she writes. “And our biases were not in harmony.”

Ironically, it was the subject of the Kennedys that would lead to Goodwin’s first and worst scandal. Eight years prior to winning the Pulitzer Prize for History for No Ordinary Time: Franklin & Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II, she published The Fitzgeralds and the Kennedys: An American Saga. In 2002, the Weekly Standard determined that she had plagiarized from several other Kennedy books to write her own, and she publicly admitted she’d “failed to provide quotation marks for phrases that I had taken verbatim.”

Goodwin subsequently paid a “substantial” sum in damages, was forced to resign from the Pulitzer Prize Board, and stepped down as a regular guest on “PBS NewsHour.” She was also dropped from the advisory board of Biographers International Organization and “disinvited” from giving a commencement speech at the University of Delaware.

Most historians could never have survived such public humiliation but, as Goodwin writes in this winning memoir, “I’ve been born with an irrepressible and optimistic temperament.” She charms when she talks about the books she’s written on “my guys” — Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Johnson — and delights as she holds forth on “my Brooklyn Dodgers.” This memoir presents Goodwin’s deepest love as she writes about her husband and the commitment they shared to an era that has yet to fulfill its promise.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

The Washington Book

by Kitty Kelley

It takes journalistic bravado to republish old columns and present them as timely or even worth rereading. The feat works for humorists like Dave Barry and Calvin Trillin, but for most columnists, it’s like driving on flat tires: “New money for old rope.” Yet Carlos Lozada meets the challenge with style and substance in The Washington Book: How to Read Politics and Politicians, a compilation of his book reviews, opinions, and essays for the Washington Post from 2004 to 2023.

It takes journalistic bravado to republish old columns and present them as timely or even worth rereading. The feat works for humorists like Dave Barry and Calvin Trillin, but for most columnists, it’s like driving on flat tires: “New money for old rope.” Yet Carlos Lozada meets the challenge with style and substance in The Washington Book: How to Read Politics and Politicians, a compilation of his book reviews, opinions, and essays for the Washington Post from 2004 to 2023.

The Pulitzer Prize winner, now at the New York Times, leads with his longest but not his strongest. Instead, he deals from the bottom of his deck, expending the first 124 pages on a section called “Leading” (rhymes with “bleating”). He recycles columns on the campaign books of presidents, vice presidents, has-beens, and wannabes. Lozada begins by presenting three chapters on Barack Obama in which he thumps the former commander-in-chief for presenting America with its “most self-referential presidency.” Next come three chapters on Hillary Clinton that challenge her “to reveal the humanity behind the capability, the person inside the politician.”

Then, in single chapters, Lozada dusts off “dedicated enabler” Mike Pence, “calcified” Dick Cheney, “lucky” Joe Biden, “feel-your-pain Democrat and policy wonk” Kamala Harris, and Ron DeSantis, who “wants the elite validation of his Ivy League credentials [Yale and Harvard Law] and the populist cred for trash-talking.” Finally, Lozada lowers the boom on Donald Trump in five devastating chapters.

Those who’ve read the critic’s first book, 2020’s What Were We Thinking: A Brief Intellectual History of the Trump Era, will not be jolted by his searing take-down of the former president, which he delivered after reading eight ghost-written books by Trump, plus 150 books about Trump, for a staggering 2,212 pages on Trump. After this pulverizing research, Lozada concludes:

“I encountered a world where bragging is breathing and insulting is talking, where repetition and contradiction come standard, where vengefulness and insecurity erupt at random.”

After his opening section, Lozada offers five more: “Fighting,” “Belonging,” “Enduring,” “Posing,” and “Imagining.” The motherlode of the book is the 26 pages he devotes to the chapter entitled “9/11 Was a Test, and We Failed.” Here, the author soars above political musings to address the ultimate subject of civilization’s existence. To write it, he read at least 20 books and several government reports, all cited, in order to present a brilliant summary of what prompted the attack on the U.S. in 2001, how we responded, and the price America paid and continues to pay.

This chapter displays scholarship at its finest, bolstered by inspired writing and thorough research worthy of a dissertation. It should be required reading for White House staff, members of Congress, and all government agencies handling national security, including the Central Intelligence Agency, the National Security Council, and the Departments of State, Defense, and Treasury. For this chapter alone, Lozada deserves a second Pulitzer — for public service.

Transitioning from consequential to comedic, he advises readers of political books not to ignore the acknowledgements. “This is where politicians disclose their debts, scratch backs, suck up and snub,” he explains. The best snub goes to Mike Pence, who does not mention Donald Trump by name in his autobiography, So Help Me God.

Lozada alerts readers to the former Texas governor Rick Perry, “often accused of being intellectually unencumbered,” who wrote in Fed Up!: Our Fight to Save America from Washington that thanking his wife was a “no-brainer,” a term that Lozada suggests Perry “avoid in any sentence describing his decision-making.” And exercised by Josh Hawley’s Manhood: The Masculine Virtues America Needs, the critic asks:

“Which is it, senator? Do American men need to man up like their forefathers or hunker down in ideological silos like their political leaders? If you are promoting manhood, why wallow in victimhood? This is a book that raises its fists, then runs for cover.”

Lozada also slams Sen. Ted Cruz for possible plagiarism in writing this about his immigrant father in A Time for Truth: Reigniting the Promise of America: “Only in a land like America is his story — is our story — even possible.” It sounds a lot like Barack Obama’s 2004 Democratic National Convention speech — “in no other country on Earth is my story even possible” — notes Lozada, adding, “Criticize a guy’s rhetoric long enough and you’re bound to start sounding like him.”

The master critic seems rocked by Marco Rubio’s acknowledgements in American Dreams: Restoring Economic Opportunity for Everyone, in which Florida’s senior senator writes, “I thank my Lord, Jesus Christ, whose willingness to suffer and die for my sins will allow me to enjoy eternal life.” In the very next sentence, Rubio thanks “My very wise lawyer, Bob Barnett.” Lozada notes the one-two punch of God and Mammon is “kind of a big deal.”

Most delightful are the parenthetical asides, frequently witty and often withering. In writing about Obama’s political ambition, Lozada observes, “The sense of destiny is not unusual among those who become president. (See Clinton, Bill.)” He compliments Obama as a writer but cuffs the former president’s lengthy 751-page memoir — “(It’s the audacity of trope).”

On Trump’s attempt to quash the book by his niece, Mary, Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created the World’s Most Dangerous Man, Lozada notes that “the suit was over money — what else.” When Hillary Clinton announced for president, she called for “an inclusive society…what I once called ‘a village’ that has a place for everyone.” Lozada’s aside: “(As if we didn’t remember).”

In the end, not every seat at Lozada’s table is prized, but he serves a bountiful feast of literary dish. You’ll walk away nourished and well-fed. (Maybe even overstuffed.)

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Strong Passions

by Kitty Kelley

The title of this book is a clever double entendre. Strong Passions refers to the scandalous divorce of a 19th-century couple named Strong, whose ruptured marriage scars their families and sears their social standing. The first few pages offer a who’s who of high society à la Edith Wharton. In fact, Barbara Weisberg introduces her narrative by quoting from Wharton’s short story “A Cup of Cold Water,” tantalizing readers with the promise of prose from the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction (in 1921, for The Age of Innocence).

The title of this book is a clever double entendre. Strong Passions refers to the scandalous divorce of a 19th-century couple named Strong, whose ruptured marriage scars their families and sears their social standing. The first few pages offer a who’s who of high society à la Edith Wharton. In fact, Barbara Weisberg introduces her narrative by quoting from Wharton’s short story “A Cup of Cold Water,” tantalizing readers with the promise of prose from the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction (in 1921, for The Age of Innocence).

Caveat emptor: Wharton’s only connection to the story told in this book is that she is 2 years old and living in New York City at the time the marital travesty unfolds between Peter Remsen Strong and Mary Emeline Stevens Strong.

The first part of this melodrama reads like a social history of the mid-1800s, when travel by ship from New York to Le Havre took three weeks, and “gentlemen” of a certain class enjoyed gambling houses, cafes, and bordellos while a few — very few — “ladies” traveled abroad. (And when they did, they were always chaperoned and shopped in Paris for “fabulous wardrobes.”)

Such details anchor the story in its era, but without much access to diaries, journals, or letters, Weisberg tells her tale in unsatisfying hypotheticals: “[Mary] would have imagined herself in the roles of wife and mother”; “She might have been eager to hear”; “Her wedding night surely was revelatory”; “Her activities…in an affluent household most likely included”; “She most likely feared.”

Weisberg, whose first book was Talking to the Dead: Kate and Maggie Fox and the Rise of Spiritualism, informs readers in this work that breastfeeding reduced the chance of pregnancy and was considered in the 19th century a form of birth control, which, the author “supposes,” is why Mary refused to wean her third daughter a few months after she was born. That baby, Edith, dies of influenza at 14 months old. On the day of the baby’s funeral, Mary, in a distraught state, admits to her husband that she’d been having an affair with his widowed brother, Edward, who conveniently enlists to fight for the Union in the Civil War. Oh, and P.S.: Mary is five months pregnant, but neither she nor Peter knows by whom.

Determined to salvage his marriage, Peter insists that his wife terminate the pregnancy. To do so, he visits his “alleged” mistress, who happens to be a “mid-wife” renting one of his properties on Waverly Place, where she advertises herself as a “woman doctor.” The author explains this is “a euphemism for a woman who did abortions.” Readers are then treated to several pages on abortion in the 1800s, as well as on adultery, the only basis for divorce in New York until 1922.

Pages later, Peter moves back to his mother’s estate in Newtown, Queens, with his elder daughter, Mamie, and sues his wife for divorce on grounds of adultery. Mary counter-sues, claiming her husband forced her to have an abortion at the hands of an abortionist with whom he was having an affair. Mary then runs away with their younger daughter, Allie. The scoundrel brother of the humiliated husband remains at war, safe from the drama.

Weisberg has presented a legitimate scandal by 19th-century standards: adultery, abortion, and abduction. “Because of the social relations and the position of the parties, and the singular charges and counter charges,” reported the New York Times, “no case before our courts for many years has attracted greater attention.”

Unfortunately, the story becomes more tabloid pottage than Wharton-esque prose. An appropriate comparison might be Mark Twain’s definition of “the difference between the almost right word and the right word” as the difference between a lightning bug and lightning.

Without conclusive evidence of what happened, the author, like the 19th-century journalists covering the case, had more questions than answers: “Where was Mary? Had she kept her little one safe? Had she indeed committed the dreadful offenses of which she was accused? Was she a victim? A seductress?” And where was the errant brother, Edward, in this “near-biblical tale of fraternal betrayal”?

After a six-week trial — the author devotes a dense, detail-laden chapter to each week — the reader is exhausted. The jury does not reach a unanimous verdict, and so Mary, who never appears in court, remains Peter’s lawfully wedded wife. At this point, patience expires, along with sympathy for either party — the wronged husband seeking revenge and the adulterous wife who escapes with her younger child.

Months later, Mary’s attorneys sue for lawyers’ fees and alimony, and the court rules in her favor. Then, in a magnanimous change of heart, Peter, “desirous of…avoiding the scandal of a second public trial,” petitions the court to provide tuition and other money to care for Allie until her 18th birthday. After six years, the divorce is finalized. Peter resumes his life as a gentleman of society, while Mary, ostracized by that society, remains in France with her daughter.

Weisberg insists in her afterword that Strong v. Strong is relevant social history, and on that point, she may be correct. But her attempt to weave the Civil War, the passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments to the Constitution, and the 1868 impeachment of President Andrew Johnson into her protracted narrative proves to be “more lightning bug than lightning.”

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

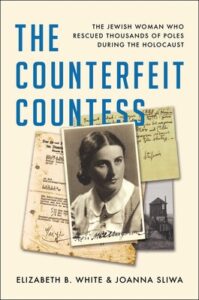

The Counterfeit Countess

by Kitty Kelley

I approach Holocaust memoirs with knee-bending respect: for the survivors who recall the atrocities they suffered during World War II so that we will never forget, and for the historians who document man’s inhumanity to man. In The Counterfeit Countess, Elizabeth B. White and Joanna Sliwa tell the story of a Polish mathematics professor who hid her identity as Janina Mehlberg (nee Pepi Spinner) when she fled the Jewish ghetto of Lwów, Poland, and reinvented herself as Countess Janina Suchodolska hundreds of miles away in Lublin, where she saved thousands of fellow Jews from annihilation.

I approach Holocaust memoirs with knee-bending respect: for the survivors who recall the atrocities they suffered during World War II so that we will never forget, and for the historians who document man’s inhumanity to man. In The Counterfeit Countess, Elizabeth B. White and Joanna Sliwa tell the story of a Polish mathematics professor who hid her identity as Janina Mehlberg (nee Pepi Spinner) when she fled the Jewish ghetto of Lwów, Poland, and reinvented herself as Countess Janina Suchodolska hundreds of miles away in Lublin, where she saved thousands of fellow Jews from annihilation.

Lublin was headquarters of Aktion Reinhard, the largest SS mass-murder operation of the Holocaust, during which 1.7 million Jews in Poland were slaughtered. German-occupied Poland was effectively ground zero for Hitler’s “final solution”; the place where the majority of the war’s Jewish victims perished; and home to some of the Third Reich’s most notorious concentration camps, including Auschwitz, Chelmno, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, and Majdanek. The latter, with its seven gas chambers, two wooden gallows, crematorium, and 227 outbuildings, was among the largest of Poland’s extermination factories — holding 250,000 prisoners — and is the focus of this book.

The authors are unsparing in describing the unrelenting and unrelieved miseries inflicted by the Nazis in decimating the Jewish population of Poland, which had the largest concentration of Jews in Europe in 1939 — 3.5 million then, fewer than 20,000 today. It becomes almost numbing to read of the killing of so many Jews, Roma (gypsies), and others at the hands of the Germans and their minions.

Nor do the authors spare the survivors, including the countess and her husband, also a professor, who abandoned their Jewish family and friends and assumed new identities as Polish Christian aristocrats in order to escape the Nazis’ brutal plans. The countess understood the animal-like desperation of humans to survive, but it’s only at the end of the book that the authors share excerpts from her unpublished memoir, in which she writes:

“What would a mother do in the face of the impossible choices put to her? There was one who, with her daughter, hid in the wardrobes of her apartment during a raid. They found her daughter, but not her. The child sobbed and screamed for her mother to save her. The mother kept silent, and survived. I know this from the mother herself who, sobbing out her story, wished herself dead instead of condemned to live with this memory.

“Another mother hid with her son in a bunker…Her son ventured out at the wrong time; he was seized and shot right there. The mother heard and remained silent.”

The countess withholds judgment on these impulses to survive, “however grim and unbearable the knowledge may be…Because while physical and psychic tortures broke many, some reacted with what one can only call moral grandeur. I know some…who helped their fellow sufferers at the cost of their own lives, who confessed to others’ ‘crimes,’ who willingly chose death over a degrading life. So, the murder of goodness was not thorough, and this fact, too, must be reported.”

The voice of the countess is so powerful that one wishes the academic co-authors, accomplished as they may be in assembling statistics and geographical details, had allowed her to tell the story in her own words, and then, perhaps, buttressed her account with their prodigious research from Holocaust museums and libraries in the U.S., Canada, Argentina, Uruguay, Germany, and Poland. Although the countess’ memoir concentrates only on what she saw and learned about human nature within the terrible crucible of occupied Poland, her words, her thoughts, and her recollections are enough to lead her story.

A small, cropped photo on the cover of the book shows the countess as a young woman with dark, shiny hair parted in the middle and pulled tightly back behind her ears in the era’s fashionable buns. Yet her biographers barely mention her appearance until 200 pages in, when they quote someone describing her as “small, dark and bright-eyed with massive braids of black hair wound round her head.”

Only in the epilogue do we get her husband’s description of her as “more than ordinarily pretty, very feminine in her style.” Aha. Now we understand how the countess — with her imposing title and good looks — was able to entice so many Nazi guards into waving her through concentration-camp gates without always examining the truckloads of food and collapsible milk urns stuffed with contraband medicine she was delivering to prisoners.

After the war, she returned to her roots as mathematician Josephine Janina Bednarski Spinner Mehlberg and immigrated to Canada with her husband. In 1961, they moved to the U.S. and became American citizens. Before “the counterfeit countess” died in 1969, she returned to Majdanek, writing in her memoir:

“I had achieved less than I had hoped, but I tried, and my efforts had made a difference, so my life had made some difference…Then I thought of those who had been broken, physically and morally, who had betrayed other lives in the hope of saving their own. Of them I spoke…None of us has the right to sit in judgment on them…There is nothing left to do for them but to remember. And in the way of my ancestors intone ‘Yisgadal, v’yiskadash,’ the Kaddish for the dead, and like the real Countess Suchodolska, ‘Kyrie Eleison, Christe Eleison.’ We will remember.”

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books