Kennedy

An Unfinished Love Story

by Kitty Kelley

The Bible’s “Parable of the Talents” (Matthew 25:14-30) instructs on how to live a worthwhile life. In that story, a master leaves his mansion to take a long trip and entrusts his silver to his servants in accord with their talents. To one, he gives five bags, to another, two bags, and to the last servant, one bag.

The Bible’s “Parable of the Talents” (Matthew 25:14-30) instructs on how to live a worthwhile life. In that story, a master leaves his mansion to take a long trip and entrusts his silver to his servants in accord with their talents. To one, he gives five bags, to another, two bags, and to the last servant, one bag.

Many months later, the master returns and asks for an accounting. The servant given five bags has invested wisely and doubled his silver, as has the second servant. The master is pleased and praises each fulsomely. The third servant says he was afraid of losing his bag, so he buried it in the ground. The master becomes irate and chastises him as wicked and lazy: “To those who use well what they are given they will have abundance in life. For those who do not, the little they have will be taken away, and they will be thrown into darkness where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.”

Such a master would embrace Doris Kearns Goodwin, for she has used well what she’s been given. Gathering her late husband’s manifold talents, she’s added her own, and burnished both, to write a glorious new memoir, An Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960s.

Richard Goodwin (1931-2018) and Doris Kearns married in 1975 in a wedding the New York Times described as blessed with “New Yorkian style, Washington power and Boston brains.” Each had established strong political allegiances beforehand, which, she admits, frequently caused marital combustion, particularly when they began working on this book, which started out being Richard’s life story. He’d decided, at the age of 80, that he was ready to tackle the 350 boxes of speeches, articles, journals, letters, and diaries he’d saved and start writing.

He asked his wife for help — “jog my memory, ask me questions” — so they hired a researcher and began what Goodwin calls their last great adventure together, which lasted until Richard, suffering from cancer, clasped her hand, declared her “a wonder,” and passed into a new frontier. After his death, she spent many years conjoining his story with her own to produce this rich and riveting chronicle of the turbulent 1960s.

Long before they wed, Richard was a wunderkind — a prodigy who coined memorable phrases that included the legendary title of Lyndon  Johnson’s legislative agenda, “The Great Society.” However, before he accepted the job in the LBJ White House, Richard sought permission from Robert F. Kennedy, and then wrote a “Dear Jackie” letter, assuring JFK’s widow, “We will all always be Kennedy men.” He remained totally committed to the Kennedys, having crafted speeches for the president and both of his politician brothers, weaving words of poetry into policy.

Johnson’s legislative agenda, “The Great Society.” However, before he accepted the job in the LBJ White House, Richard sought permission from Robert F. Kennedy, and then wrote a “Dear Jackie” letter, assuring JFK’s widow, “We will all always be Kennedy men.” He remained totally committed to the Kennedys, having crafted speeches for the president and both of his politician brothers, weaving words of poetry into policy.

Goodwin, on the other hand, was fiercely loyal to President Johnson, having worked closely with him in the White House and, later, on his memoir. She admits being troubled by many passages in her husband’s diaries, particularly those dealing with Bobby Kennedy’s animosity toward Johnson and his insensitivity to “the mammoth problems that beset the new president and the country at large.” She became irate when she found a memo her husband had written quoting RFK about the choice of a running mate on LBJ’s 1964 presidential ticket: “When the time comes we’ll tell him who we want for vice-president.”

“Who does he think he is?” she asked her husband, who explained Kennedy was simply venting grief over his brother’s assassination. “It’s the arrogance of ‘we’ll tell him who we want’ that sticks in my craw.”

The couple’s clash of political loyalties continued “provoking tension,” as Goodwin insisted that civil rights, medical care for the aged, federal aid for education, and an overhaul of immigration only became law under President Johnson, while Richard countered that President Kennedy’s leadership set the tone and spirit of the decade. “Both of us looked back upon these years with a decided bias,” she writes. “And our biases were not in harmony.”

Ironically, it was the subject of the Kennedys that would lead to Goodwin’s first and worst scandal. Eight years prior to winning the Pulitzer Prize for History for No Ordinary Time: Franklin & Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II, she published The Fitzgeralds and the Kennedys: An American Saga. In 2002, the Weekly Standard determined that she had plagiarized from several other Kennedy books to write her own, and she publicly admitted she’d “failed to provide quotation marks for phrases that I had taken verbatim.”

Goodwin subsequently paid a “substantial” sum in damages, was forced to resign from the Pulitzer Prize Board, and stepped down as a regular guest on “PBS NewsHour.” She was also dropped from the advisory board of Biographers International Organization and “disinvited” from giving a commencement speech at the University of Delaware.

Most historians could never have survived such public humiliation but, as Goodwin writes in this winning memoir, “I’ve been born with an irrepressible and optimistic temperament.” She charms when she talks about the books she’s written on “my guys” — Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Johnson — and delights as she holds forth on “my Brooklyn Dodgers.” This memoir presents Goodwin’s deepest love as she writes about her husband and the commitment they shared to an era that has yet to fulfill its promise.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

King: A Life

by Kitty Kelley

They said one to another

Behold here cometh the Dreamer

Let us slay him

And we shall see what will become of his dreams.

– Genesis 37:19-20

These words are carved into the cement plaque that rests outside room 306 of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. They mark the place where Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968. The dreamer’s death transformed his murder site into a shrine that now houses the National Civil Rights Museum, where King’s life continues to inspire, drawing thousands of visitors every year.

These words are carved into the cement plaque that rests outside room 306 of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. They mark the place where Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968. The dreamer’s death transformed his murder site into a shrine that now houses the National Civil Rights Museum, where King’s life continues to inspire, drawing thousands of visitors every year.

Scholars and historians have long explored the legacy of the Baptist minister from Georgia who preached a gospel of nonviolence. Deservedly, many King biographies have won prestigious prizes, among them Taylor Branch’s magisterial trilogy: Parting the Waters, Pillar of Fire, and At Canaan’s Edge. Additional tributes to King include I May Not Get There with You by Michael Eric Dyson; Bearing the Cross by David J. Garrow; Let the Trumpet Sound by Stephen B. Oates; Death of a King by Tavis Smiley; The Promise and the Dream by David Margolick; and The Sword and the Shield by Peniel E. Joseph.

Now comes Jonathan Eig with King: A Life, which promises “to recover the real man from the gray mist of hagiography.” Regrettably, says the author, “In the process of canonizing King, we’ve defanged him…[but] King was a man, not a saint, not a symbol.” In removing the mantle, Eig presents here an orator of soaring rhetoric who unapologetically plagiarized his speeches, saying his goal was to move audiences. Even King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech seems to have had its origins in Langston Hughes’ poems “I Dream a World” and “Dream Deferred.”

Misappropriating others’ work is a grievous sin for scholars, a “bad habit,” Eig writes, that King started in high school and continued as a graduate student at Crozier and later at Boston University, where he earned his Ph.D. with a dissertation that contained more than 50 sentences lifted from someone else’s work. By contrast, readers will note how generous Eig is to his own sources, giving previous biographers their due and quoting many by name in his text, not simply relegating them to chapter notes in the back of the book. Just as noteworthy is Eig’s appreciation for all who contributed to King: A Life; he lists each name under “Acknowledgements: Beloved Community.”

In this biography, his sixth book, Eig writes like an Olympic diver who jackknifes off the high board, slicing the water without a ripple. He performs with sheer artistry, like Picasso paints and Astaire dances. In unspooling the life of King, Eig presents a complicated man who attempted suicide twice; who was plagued by clinical depression so deep it required hospitalization; who chewed his nails; and who gave up the “true love” of his life, a white woman named Betty Moitz, because he realized, with her, he would never be accepted as a preacher in Black churches. The late Harry Belafonte, who himself married a white woman, told Eig that King never stopped talking about Moitz, and King’s mentor in graduate school described him after the break-up as “a man with a broken heart,” adding, “he never recovered.”

Although he married Coretta Scott and had four children with her, King pursued many women throughout his life. While Eig is unsparing about those extramarital affairs, he writes gently: “King’s busy schedule of travel also afforded him opportunities to spend time with women other than Coretta.”

The author also draws interesting similarities between King and John F. Kennedy, both of whom indelibly marked their era:

- Both were influenced by powerful (and philandering) fathers.

- Both enjoyed a privileged lifestyle above their contemporaries.

- Both were accused of plagiarism.

- Both experienced discrimination (JFK as an Irish Catholic; King as a Black man).

- Both excelled as public speakers.

- Both were assassinated.

King was particularly threatened by the never-made-public tape recordings FBI director J. Edgar Hoover ordered, turning federal agents into bloodhounds and instructing them to install bugs wherever King traveled. Hoover distributed copies of the recordings, which contained evidence of “unnatural sexual acts,” to President Lyndon Johnson, White House officials, and journalists in order to undermine King’s credibility. To further ensure his ruin, Hoover met with a group of woman journalists and declared King the country’s “most notorious liar.”

King reportedly wept over the slur to his life’s work but managed a masterful response to the press:

“I cannot conceive of Mr. Hoover making a statement like this without being under extreme pressure. He has apparently faltered under the awesome burden, complexities and responsibilities of his office. Therefore, I cannot engage in a public debate with him. I have nothing but sympathy for this man who has served his country well.”

By opposing the “immoral” war in Vietnam, King, who’d received the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize, drew the unremitting ire of Johnson. As Eig writes, King’s “conscience would not allow him to cooperate with an advocate and purveyor of war.” Infuriated, Johnson never forgave the man who’d given his presidency its three greatest legislative achievements: the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

While Eig reveals the flawed man behind the myth, Martin Luther King Jr. still stands tall and strong enough to shoulder Shakespeare’s words from “Measure for Measure”:

They say best men are molded out of faults,

And, for the most, become much more the better

For being a little bad

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

(Color photo of Martin Luther King Jr. by Stanley Tretick, 1966, from Let Freedom Ring.)

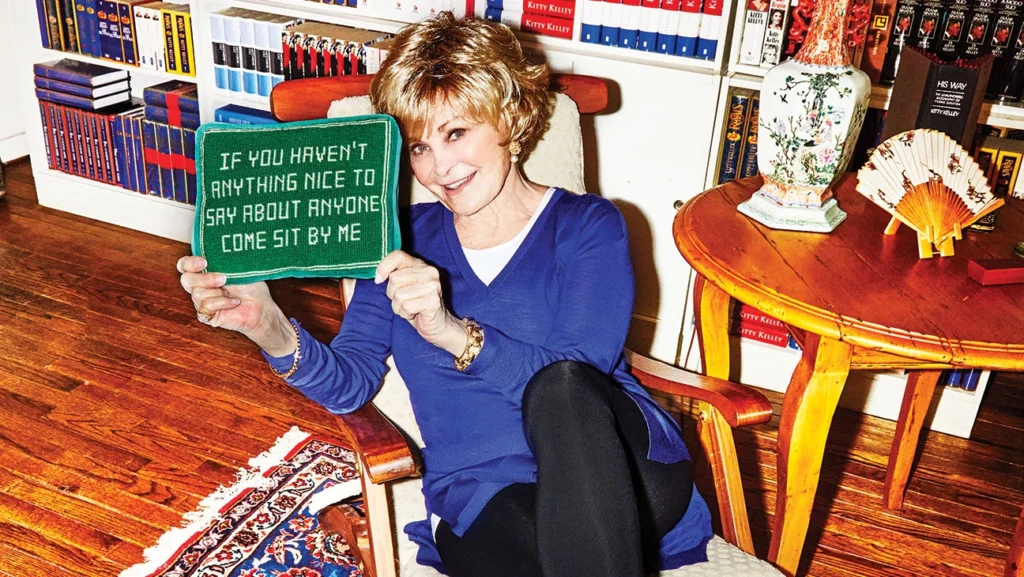

Kitty Kelley Wins 2023 BIO Award

Kitty Kelley has won the 14th BIO Award, bestowed annually by the Biographers International Organization to a distinguished colleague who has made major contributions to the advancement of the art and craft of biography.

Widely regarded as the foremost expert and author of unauthorized biography, Kelley has displayed courage and deftness in writing unvarnished accounts of some of the most powerful figures in politics, media, and popular culture. Of her art and craft, Kelley said, in American Scholar, “I do not relish living in a world where information is authorized, sanitized, and homogenized. I read banned books, I applaud whistleblowers, and I reject any suppression by church or state. To me, the unauthorized biography, which requires a combination of scholarly research and investigative reporting, is best directed at those figures still alive and able to defend themselves, who exercise power over our lives. . . . I firmly believe that unauthorized biography can be a public service and a boon to history.”

Among other awards, Kelley was the recipient of: the 2005 PEN Oakland/Gary Webb Anti-Censorship Award; the 2014 Founders’ Award for Career Achievement, given by the American Society of Journalists and Authors; and, in 2016, a Lifetime Achievement Award, given by The Washington Independent Review of Books. Her impressive list of lectures and presentations includes: leading a winning debate team in 1993, at the University of Oxford, under the premise “This House Believes That Men Are Still More Equal Than Women;” and, in 1998, a lecture at the Harvard Kennedy School for Government on the subject “Public Figures: Are Their Private Lives Fair Game for the Press?” In addition, Kelley was named by Vanity Fair to its Hall of Fame as part of the “Media Decade” and she has been a New York Times bestseller multiple times.

For over 30 years, Kelley has been a full-time freelance writer. In addition to the American Scholar, her writing has appeared in The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, Newsweek, Ladies’ Home Journal, The Chicago Tribune, The Washington Times, The New Republic, and McCall’s. She is also a frequent contributor to The Washington Independent Review of Books.

Heather Clark, chair of the BIO Awards Committee, said: “The Awards committee is thrilled to recognize Kitty Kelley for her outstanding contributions to biography over nearly six decades. We admire her courage in speaking truth to power, and her determination to forge ahead with the story in the face of opposition from the powerful figures she holds accountable. The committee would also like to recognize Kitty’s many years of service to BIO, especially her fundraising prowess and commitment to growing BIO’s membership ranks. Kitty is a force of nature and a deeply inspiring figure who deserves the highest recognition from BIO for her contributions to advancing the art and craft of biography.”

Of her award, Kelley said, “I’m dazzled by the BIO honor and feel like Cinderella when the glass slipper fit. Please don’t wake me up from this dream.”

Previous BIO Award winners are Megan Marshall, David Levering Lewis, Hermione Lee, James McGrath Morris, Richard Holmes, Candice Millard, Claire Tomalin, Taylor Branch, Stacy Schiff, Ron Chernow, Arnold Rampersad, Robert Caro, and Jean Strouse.

Kelley will give the keynote address at the 2023 BIO Conference, on Saturday, May 20.

2023 BIO Award Winner Kitty Kelley interviewed by Heath Hardage Lee, March 28, 2023

My Place in the Sun

by Kitty Kelley

Sometimes, the sons of famous fathers are cursed. “They’re born on third base and think they’ve hit a triple,“ according to the adage. Seldom do they hit a home run. Not so the namesake of director, producer, screenwriter, and cinematographer George Stevens (1904-1975), who elevated films from entertainment to enlightenment with A Place in the Sun, Shane, Giant, The Diary of Anne Frank, and The Greatest Story Ever Told.

Sometimes, the sons of famous fathers are cursed. “They’re born on third base and think they’ve hit a triple,“ according to the adage. Seldom do they hit a home run. Not so the namesake of director, producer, screenwriter, and cinematographer George Stevens (1904-1975), who elevated films from entertainment to enlightenment with A Place in the Sun, Shane, Giant, The Diary of Anne Frank, and The Greatest Story Ever Told.

His son — “Young George,” “Georgie,” or “George, Jr.” — was born on third base, but now he’s nearly 90 years old and is proudly waving his scorecard in My Place in the Sun: Life in the Golden Age of Hollywood and Washington.

George Stevens Jr. is Tinsel Town royalty. He springs from five generations of stage actors, silent screen stars, and drama critics, including his father. Stevens père, a two-time Academy Award winner, was a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army Signal Corps during WWII and  headed a film unit that documented the D-Day landings at Normandy, the liberation of Paris, and the Allied discoveries of the Duben labor camp and the concentration camp at Dachau.

headed a film unit that documented the D-Day landings at Normandy, the liberation of Paris, and the Allied discoveries of the Duben labor camp and the concentration camp at Dachau.

Stevens fils found these treasures and more in his late father’s storage bin and put them to good use in this work, a phenomenal history of Hollywood that’s as much a paean to a beloved father as it is an accomplished record of the adoring son, who propelled the family legacy forward into television (at 27, George Jr. was directing Alfred Hitchcock Presents for CBS) and prize-winning documentaries. In addition, he founded the American Film Institute (AFI) in 1966 and, for 38 years, produced The Kennedy Center Honors.

There are more names dropped in this memoir than in the Book of Jehovah. “Bobby and Ethel”; “My good friend, Tom Brokaw”; “Teddy”; “My rabbi, Vernon Jordan”; and “My buddy Art Buchwald.” One wonders if Stevens has ever known a no-name plumber or lowly key grip. Here’s just a sample of his life on the celebrity circuit:

“My calendar shows days filled with organizing a new [film] school and stimulating evenings during which I spread word about AFI to the Hollywood community; ‘Dinner at the [Gregory] Pecks — Mr. and Mrs. Jean Renoir, Omar Sharif and Barbra Streisand; dinner at home — John Huston and Shirley MacLaine; dinner at Danny Kaye’s with Pecks and Isaac Stern; dinner at George Englund’s w/Warren Beatty, Paul Newman, Robert Towne.’”

Despite the marquee names (and there are pages of them), there is no braggadocio. In fact, there’s a bit of the fanboy in this man who once asked President Clinton to sign their scorecard after playing golf together. George Stevens Jr. displays the self-deprecating style of someone enthralled by his work, engaged by his politics, and enriched by his friends. His memoir, gracefully written, shows a man who knows that blessings accrue to those who take the high road.

Accustomed to flying smooth skies, Stevens was not prepared for the turbulence he encountered when David M. Rubenstein, chair of the Kennedy Center, forced him out as producer of The Kennedy Center Honors. Stevens writes that Rubenstein came to his office on a Good Friday in what “proved to be a disturbing and somewhat bizarre meeting…[Rubenstein] seemed to apologize, saying this was his most difficult meeting since the time he fired George H.W. Bush and James A. Baker from his Carlyle enterprise.” He continues:

“Again, insufficient paranoia had let me down. David’s riches, after all, had come from hostile takeovers of corporations — ousting existing management, cutting costs and reaping windfalls. On reflection, my response was less tempered than I would have liked. ‘I think you’ll have to look around for a long time to find producers who will give you five consecutive Emmys.’”

Since parting ways with the Stevens Company in 2014, The Kennedy Center Honors has won a few Emmys but not yet “five consecutive” ones. For his part, Stevens writes, “It’s too bad it ended the way it did, but the passage of time now allows me to look back on the somewhat indecorous circumstances of my departure with what Wordsworth called ‘emotion recollected in tranquility.’”

Just when the reader is floating on the sweet vapors of a golden life among the good and the great, Stevens brings you to your knees with the worst that can befall a parent. In 2015, he and his wife, Elizabeth, lost their 49-year-old son, Michael, to stomach cancer. This chapter, entitled “Courage,” is a chapter no parent ever wants to write. Stevens keeps it short:

Just when the reader is floating on the sweet vapors of a golden life among the good and the great, Stevens brings you to your knees with the worst that can befall a parent. In 2015, he and his wife, Elizabeth, lost their 49-year-old son, Michael, to stomach cancer. This chapter, entitled “Courage,” is a chapter no parent ever wants to write. Stevens keeps it short:

“Not a day goes by that I do not think of Michael Stevens.”

He ends his book as he began it — by extolling the work that has defined his life for decades. He quotes Bertrand Russell, who wrote about the same subject at the same age in “The Pros and Cons of Reaching Ninety”: “A long habit of work with some purpose that one believes is important is a hard habit to break.”

Last seen, Stevens was heading for his office “to ponder stories that might become films, though an awareness that each new film is a commitment of years makes me a little less keen to toss my cap over the wall. However, now that the storytelling juices that have been devoted to this book are freed up, who knows what lies ahead.”

We can only hope.collection

(Photos: George Stevens Sr. with George Stevens Jr., Michael Stevens from Stevens Family Collection, Margaret Herrick Library and the Academy Film Archive https://www.oscars.org/collection-highlights/stevens-family-collection/?)

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Undelivered

by Kitty Kelley

“For all sad words of tongue and pen,

The saddest are these, ‘It might have been.’”

These woeful words from Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier might apply to politicians and lovers and horses who’ve never made the winner’s circle. Those losses are particularly painful for politicians who are expected to concede gracefully and congratulate the fiend who just walloped them. As Rep. Morris Udall said after losing the 1976 Democratic nomination for president, “It’d be less painful to get mowed down by an 18-wheeler.”

These woeful words from Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier might apply to politicians and lovers and horses who’ve never made the winner’s circle. Those losses are particularly painful for politicians who are expected to concede gracefully and congratulate the fiend who just walloped them. As Rep. Morris Udall said after losing the 1976 Democratic nomination for president, “It’d be less painful to get mowed down by an 18-wheeler.”

Hillary Clinton felt the same way in 2016 after winning the popular vote for president by over 4 million votes but losing the Electoral College by 306-232, and thus the presidency. The former secretary of state/U.S. senator/first lady was poised to claim victory with prepared remarks thanking “my fellow Americans” for “reaching for unity, decency and what President Lincoln called ‘the better angels of our nature.’”

But those better angels flew away as Clinton acknowledged her loss to Donald J. Trump with civility and just a  couple of tears. After thanking her family, staff, volunteers, and contributors, she apologized to them, becoming the first presidential candidate in history to say “I’m sorry” in a concession speech.

couple of tears. After thanking her family, staff, volunteers, and contributors, she apologized to them, becoming the first presidential candidate in history to say “I’m sorry” in a concession speech.

Now we’re finding out what Clinton would’ve said as president-elect had she won the campaign that cost over $581 million. Her six-page victory speech, never given, is reported in full by Jeff Nussbaum in his creative new book, Undelivered: The Never-Heard Speeches that Would Have Rewritten History.

Some of the unspoken speeches unearthed by Nussbaum’s dogged research and informative text spark jump-up-and-down joy, particularly those in the section entitled “The Fog of War, The Path to Peace.” Each of its three segments is noteworthy, beginning with the words of apology General Dwight D. Eisenhower would’ve delivered if the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944, had failed.

“The troops, the air and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do,” he wrote in a brief, four-sentence statement. “If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt, it is mine alone.” Nussbaum, a speechwriter for Democrats, recognizes Eisenhower’s words as “an object lesson in the language of leadership and responsibility.”

Knowing that “victory has a hundred fathers and defeat is an orphan,” President John F. Kennedy prepared a never-delivered speech to the nation in 1962 to announce airstrikes on Cuba “to remove a major nuclear weapons build up.” The president had gathered his top cabinet officers — hawks and doves alike — to debate the issue and discuss what to do.

“Each one of us was being asked to make a recommendation which would affect the future of all mankind,” wrote Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy of the Cuban Missile Crisis, “a recommendation which, if wrong and if accepted, could mean the destruction of the human race.” For 13 days, the U.S. teetered on the edge of war with the Soviet Union, until Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev blinked and removed his missiles.

The third example of an undelivered speech that might’ve changed history is Emperor Hirohito’s apology for Japan’s role in World War II, which he wrote in 1948, lamenting the “countless corpses…[left]…on the battlefield [and] the countless people [who] lost their lives…Our heart is seared with grief. We are deeply ashamed…for our lack of virtue.”

Now to the bits that don’t stir jump-up-and-down joy. Much of Nussbaum’s book reads like a garrulous guy on a binge while his editor is A.W.O.L. The author meanders back and forth from a third-person narrative to first-person asides, political anecdotes, pesky footnotes, and lame jokes (see the one about St. Peter and speechwriters). He jams his book to the brim with historical information, proving that he’s read widely, and is hellbent on sharing every bit of his findings, which he piles into 374 pages of main text, 38 pages of notes, a 30-page bibliography, and a 28-page appendix. (Dear Santa: Please put a copy of Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style in Nussbaum’s Christmas stocking.)

An example of what might be described as logorrhea begins in the first chapter and deals with late congressman John Lewis’ proposed speech at the 1963 March on Washington. Lewis’ original remarks were deemed too fiery for Archbishop Patrick O’Boyle, who refused to make the morning’s invocation if Lewis didn’t tone down his rhetoric. March organizers pressured Lewis, saying that without the Irish Catholic prelate, they might lose support from the Irish Catholic president, which would influence Congress and doom Civil Rights legislation. So, Lewis compromised.

An example of what might be described as logorrhea begins in the first chapter and deals with late congressman John Lewis’ proposed speech at the 1963 March on Washington. Lewis’ original remarks were deemed too fiery for Archbishop Patrick O’Boyle, who refused to make the morning’s invocation if Lewis didn’t tone down his rhetoric. March organizers pressured Lewis, saying that without the Irish Catholic prelate, they might lose support from the Irish Catholic president, which would influence Congress and doom Civil Rights legislation. So, Lewis compromised.

At this point, the author-in-need-of-an-editor interrupts his story of Lewis’ speech to relate his own stories of being a speechwriter at the Democratic National Convention from 2000 through 2020. He rambles on about Melania Trump, who lifted from Michelle Obama’s speech, Al Sharpton’s refusal to use a teleprompter, and Barney Frank’s speech impediment, and includes brief mentions of 2012 Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney, his wife, Anne, and the GOP convention’s keynote speaker, New Jersey governor Chris Christie. (P.S. to Santa: Please add Arthur Plotnik’s Spunk & Bite: A Writer’s Guide to Bold, Contemporary Style to that stocking.)

Eventually, Nussbaum circles back to the dilemma facing Lewis, but only for a few pages before he interrupts the narrative again with more reflections on his own speechwriting. Then, and only then (thank you, Jesus), does he return to finish the story of Lewis and his 1963 speech.

Note to readers: Lewis’ undelivered speech is just the book’s first chapter. You’ve got 14 more to go. (P.P.S. to Santa: Forget your sleigh. Use FedEx.)

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

(Photos: John Lewis at the Lincoln Memorial, 1963 © Estate of Stanley Tretick; Hillary Clinton conceding, 2016, PBS/YouTube)

Queen of the Unauthorized Biography Spills Her Own Secrets

By Seth Abramovitch

There was, not that long ago, a name whose mere invocation could strike terror in the hearts of the most powerful figures in politics and entertainment.

That name was Kitty Kelley.

If it’s unfamiliar to you, ask your mother, who likely is in possession of one or more of Kelley’s best-selling biographies — exhaustive tomes that peer unflinchingly (and, many have claimed, nonfactually) into the personal lives of the most famous people on the planet.

“I’m afraid I’ve earned it,” sighs Kelley, 79, of her reputation as the undisputed Queen of the Unauthorized Biography. “And I wave the banner. I do. ‘Unauthorized’ does not mean untrue. It just means I went ahead without your permission.”

That she did. Jackie Onassis, Frank Sinatra, Nancy Reagan — the more sacred the cow, the more eager Kelley was to lead them to slaughter. In doing so, she amassed a list of enemies that would make a despot blush. As Milton Berle once cracked at a Friars Club roast, “Kitty Kelley wanted to be here tonight, but an hour ago she tried to start her car.”

Only a handful of contemporary authors have achieved the kind of brand recognition that Kelley has. At the height of her powers in the early 1990s, mentions of the ruthless journo with the cutesy name would pop up everywhere from late night monologues to the funny pages. (Fully capable of laughing at herself, her bathroom walls are covered in framed cartoons drawn at her expense.)

Kelley is hard to miss around Washington, D.C. She drives a fire-engine red Mercedes with vanity plates that read “MEOW.” The car was a gift from former Simon & Schuster chief Dick Snyder, who was determined to land Kelley’s Nancy Reagan biography.

“Simon & Schuster said, ‘Kitty, Dick really wants the book. What will it take to prove that?’ ” she recalls. “I said,  ‘A 560 SL Mercedes, bright red, Palomino interior.’ ‘We’ll be back to you.’ ” She insists she was only kidding. But a few days later, Kelley answered the phone and was directed to walk to the nearest corner: “Your bright red 560 SL is sitting there waiting for you.” Sure enough, there it was. The “MEOW” plates were a surprise gift from the boyfriend who would become her second husband, Dr. John Zucker.

‘A 560 SL Mercedes, bright red, Palomino interior.’ ‘We’ll be back to you.’ ” She insists she was only kidding. But a few days later, Kelley answered the phone and was directed to walk to the nearest corner: “Your bright red 560 SL is sitting there waiting for you.” Sure enough, there it was. The “MEOW” plates were a surprise gift from the boyfriend who would become her second husband, Dr. John Zucker.

Ask Kelley how many books she has sold, and she claims not to know the exact number. It is many, many millions. Her biggest sellers — 1986’s His Way, about Frank Sinatra, and 1991’s Nancy Reagan: The Unauthorized Biography, began with printings of a million each, which promptly sold out. “But they’ve gone to 12th printings, 14th printings,” she says. “I really couldn’t tell you how many I’ve sold in total.” She does recall first breaking into The New York Times‘ best-seller charts, with 1978’s Jackie Oh! “I remember the thrill of it. I remember how happy I was. It’s like being prom queen,” she says. “Which I actually was about 100 years ago.”

Regardless of one’s opinions about Kelley, or her methodology, there can be no denying that her brand of take-no-prisoners celebrity journalism — the kind that in 2022 bubbles up constantly in social media feeds in the form of TMZ headlines and gossipy tweets — was very much ahead of its time.

In fact, a detail from Kelley’s 1991 Nancy Reagan biography trended in December when Abby Shapiro, sister of conservative commentator Ben Shapiro, tweeted side-by-side photos of Madonna and the former first lady. “This is Madonna at 63. This is Nancy Reagan at 64. Trashy living vs. Classic living. Which version of yourself do you want to be?” read the caption. Someone replied with an excerpt from Kelley’s biography that described Reagan as being “renowned in Hollywood for performing oral sex” and “very popular on the MGM lot.” The excerpt went viral and launched a wave of memes. “It doesn’t fit with the public image. Does it? It just doesn’t. And the source on that was Peter Lawford,” says Kelley, clearly tickled that the detail had resurfaced.

While amplifying those kinds of rumors might not suggest it, in many eyes, Kelley is something of a glass-ceiling shatterer. “Back when she started in the 1970s, it was a largely male profession,” says Diane Kiesel, a friend of Kelley’s who is a judge on the New York Supreme Court. “She was a trailblazer. There weren’t women writing the kind of hard-hitting books she was writing. I’m sure most of her sources were men.”

But what of her methodology? Kelley insists she never sets out to write unauthorized biographies. Since Jackie Oh!, she has always begun her research by asking her subjects to participate, often multiple times. She is invariably turned down, then continues about the task anyway. She’s also known to lean toward blind sourcing and rely on notes, plus tapes and photographs, to back up the hundreds of interviews that go into every book.

“Recorders are so small today, but back then it was very hard to carry a clunky tape recorder around and slap it on the table in a restaurant and not have all of that ambient noise,” she says. To prove the conversations happened, Kelley devised a system in which she would type up a thank-you note containing the key details of their meeting — location, date and time — and mail it to every subject, keeping a copy for herself. If a subject ever denied having met with her, she would produce the notes from their conversation and her copy of the thank-you note.

So far, the system has worked. While many have tried to take her down, the ever-grinning Kelley has never been successfully sued by a source or subject.

Now 79, she lives in the same Georgetown townhouse she purchased with her $1.5 million advance (that’s $4 million adjusted for inflation) for His Way, which the crooner unsuccessfully sued to prevent from even being written.

Among the skeletons dug up by Kelley in that 600-page opus: that Ol’ Blue Eyes’ mother was known around  Hoboken, New Jersey, as “Hatpin Dolly” for a profitable side hustle performing illegal abortions. Sinatra’s daughter Nancy Sinatra said the family “strangled on our pain and anger” over the book’s release, while her sister, Tina, said it caused her father so much stress, it forced him to undergo a seven-and-a-half-hour surgical procedure on his colon.

Hoboken, New Jersey, as “Hatpin Dolly” for a profitable side hustle performing illegal abortions. Sinatra’s daughter Nancy Sinatra said the family “strangled on our pain and anger” over the book’s release, while her sister, Tina, said it caused her father so much stress, it forced him to undergo a seven-and-a-half-hour surgical procedure on his colon.

Giggly, vivacious and 5-foot-3, Kelley presents more like a kindly neighbor bearing blueberry muffins than the most infamous poison-pen author of the 20th century. “I seem to be doing more book reviewing than book writing these days,” she says in one of our first correspondences and points me to a review of a John Lewis biography published in the Washington Independent Review of Books.

She has not tackled a major work since 2010’s Oprah — a biography of Oprah Winfrey touted ahead of its release by The New Yorker as “one of those King Kong vs. Godzilla events in celebrity culture” but which fizzled in the marketplace, barely moving 300,000 copies. Among its allegations: that Winfrey had an affair early in her career with John Tesh — of Entertainment Tonight fame — and that, according to a cousin, the talk show host exaggerated tales of childhood poverty because “the truth is boring.”

“We had a falling out because I didn’t want to publish the Oprah book,” says Stephen Rubin, a consulting publisher at Simon & Schuster who grew close to Kelley while working with her at Doubleday on 2004’s The Family: The Real Story of the Bush Dynasty.

“I told her that audience doesn’t want to read a negative book about Saint Oprah. I don’t think it’s something she should have even undertaken. We have chosen to disagree about that.”

The book ended up at Crown. It would be nine months before Kelley would speak to Rubin again. They’ve since reconciled. “She’s no fun when she’s pissed,” Rubin notes.

Adds Kelley of Winfrey’s reaction to the book: “She wasn’t happy with it. Nobody’s happy with [an unauthorized] biography. She was especially outraged about her father’s interview.” She is referencing a conversation she had, on the record, with Winfrey’s father, Vernon Winfrey, in which he confirmed the birth of her son, who arrived prematurely and died shortly after birth.

But Kelley says the backlash to Oprah: A Biography and the book’s underwhelming sales had nothing to do with why she hasn’t undertaken a biography since. Rather, her husband, a famed allergist in the D.C. area who’d give a daily pollen report on television and radio, died suddenly in 2011 of a heart attack. “John was the great love of her life,” says Rubin. “He was an irresistible guy — smart, good-looking, funny and mad for Kitty.”

“Boy, I was knocked on my heels,” she says of Zucker’s death. “He hated the cold weather. He insisted we go out to the California desert. We were in the desert, and he died at the pool suddenly. I can’t account for a couple of years after that. It was a body blow. I just haven’t tackled another biography since.”

A decade having passed, Kelley does not rule out writing another one — she just hasn’t yet found a subject worthy of her time. “I can’t think of anyone right now who I would give three or four years of my life to,” Kelley says. “It’s like a college education.”

For fun, I throw out a name: Donald Trump. Kelley shakes her head vigorously. “I started each book with real respect for each of my subjects,” she says. “And not just for who they were but for what they had accomplished and the imprint that they had left on society. I can’t say the same thing about Donald Trump. I would not want to wrap myself in a negative project for four years.”

“You know,” I interrupt, “I’m imagining people reading that quote and saying, ‘Well, you took ostensibly positive topics and turned them into negative topics.’ How would you respond to that?”

“I would say you’re wrong,” Kelley replies. “That’s what I would say. I think if you pick up, I don’t know — the Frank Sinatra book, Jackie Oh!, the Bush book — yes, you’re going to see the negatives and the positives, which we all have. But I think you’ll come out liking them. I mean, we don’t expect perfection in the people around us, but we seem to demand it in our stars. And yet, they’re hardly paragons. Each book that I’ve written was a challenge. But I would think that if you read the book, you’re going to come out — no matter what they say about the author — you’re going to come out liking the subject.”

***

Kelley arrived in the nation’s capital in 1964. She was 22 and, through the connections of her dad, a powerful attorney from Spokane, Washington, she landed an assistant job in Democratic Sen. Eugene McCarthy’s office. She worked there for four years, culminating in McCarthy’s 1968 presidential bid. It was a tumultuous time. McCarthy’s Democratic rival, Robert F. Kennedy, was gunned down in Los Angeles at a California primary victory party on June 5. When Hubert Humphrey clinched the nomination that August amid the DNC riots in Chicago, Kelley’s dreams of a future in a McCarthy White House were dashed, and she decided a life in politics was not for her.

“But I remain political,” Kelley clarifies. “I am committed to politics and have been ever since I worked for Gene McCarthy. I was against the war in Vietnam. I don’t come from that world. I come from a rich, right-wing Republican family. My siblings avoid talking politics with me.”

In 1970, she applied for a researcher opening in the op-ed section at The Washington Post. “It was a wonderful job,” she recalls. “I’d go into editorial page conferences. And whatever the writers would be writing, I would try and get research for them. Ben Bradlee’s office was right next to the editorial page offices. And if he had both doors open, I would walk across his office. He was always yelling at me for doing it.”

According to her own unauthorized biography — 1991’s Poison Pen, by George Carpozi Jr. — Kelley was fired for taking too many notes in those meetings, raising red flags for Bradlee, who suspected she might be researching a book about the paper’s publisher, Katharine Graham. Kelley says the story is not true.

“I have not heard that theory, but I will tell you I loved Katharine Graham, and when I left the Post, she gave me a gift. She dressed beautifully, and when the style went from mini to maxi skirts —because she was tall and I am not, I remember saying, ‘Mrs. Graham, you’re going to have to go to maxis now. And who’s going to get your minis?’ She laughed. It was very impudent. But then I was handed a great big box with four fabulous outfits in them — her miniskirts.”

Kelley says she left the Post after two years to pursue writing books and freelancing. She scored one of the bigger scoops of 1974 when the youngest member of the upper house — newly elected Democratic Sen. Joe Biden of Delaware, then 31 — agreed to be profiled for Washingtonian, a new Beltway magazine.

Biden was still very much in mourning for his wife and young daughter, killed by a hay truck while on their way to buy a Christmas tree in Delaware on Dec. 18, 1972. The future president’s two young sons, Beau and Hunter, survived the wreck; Biden was sworn into the Senate at their hospital bedsides.

After the accident, Biden developed an almost antagonistic relationship to the press. But his team eventually softened him to the idea of speaking to the media. That was precisely when Kelley made her ask.

Biden would come to deeply regret the decision. The piece, “Death and the All-American Boy,” published on June 1, 1974, was a mix of flattery (Kelley writes that Biden “reeks of decency” and “looks like Robert Redford’s Great Gatsby”), controversy (she references a joke told by Biden with “an antisemitic punchline”) and, at least in Biden’s eyes, more than a little bad taste.

The piece opens: “Joseph Robinette Biden, the 31-year-old Democrat from Delaware, is the youngest man in the Senate, which makes him a celebrity of sorts. But there’s something else that makes him good copy: Shortly after his election in November 1972 his wife Neilia and infant daughter were killed in a car accident.”

Later, Kelley writes, “His Senate suite looks like a shrine. A large photograph of Neilia’s tombstone hangs in the inner office; her pictures cover every wall. A framed copy of Milton’s sonnet ‘On His Deceased Wife’ stands next to a print of Byron’s ‘She Walks in Beauty.’ “

But it was one of Biden’s own quotes that most incensed the future president.

She writes: ” ‘Let me show you my favorite picture of her,’ he says, holding up a snapshot of Neilia in a bikini. ‘She had the best body of any woman I ever saw. She looks better than a Playboy bunny, doesn’t she?’ “

“I stand by everything in the piece,” says Kelley. “I’m sorry he was so upset. And it’s ironic, too, because I’m one of his biggest supporters. It was 48 years ago. I would hope we’ve both grown. Maybe he expected me to edit out [the line about the bikini], but it was not off the record.” Still, she admits her editor, Jack Limpert, went too far with the headline: “I had nothing to do with that. I was stunned by the headline. ‘Death and the All-American Boy.’ Seriously?”

It would be 15 years before Biden gave another interview, this time to the Washington Post‘s Lois Romano during his first presidential bid, in 1987. Biden, by then remarried to Jill Biden, recalled to Romano, “[Kelley] sat there and cried at my desk. I found myself consoling her, saying, ‘Don’t worry. It’s OK. I’m doing fine.’ I was such a sucker.”

Kelley’s first book wasn’t a biography at all. “It was a book on fat farms,” she says, which was based on a popular article she’d written for Washington Star News on San Diego’s Golden Door — one of the country’s first luxury spas catering to celebrity clientele like Natalie Wood, Elizabeth Taylor and Zsa Zsa Gabor.

“On about the third day, the chef came out, and he said, ‘Would you like a little something?’ ” says Kelley. “He was Italian. I said, ‘Yes, I’m so hungry.’ And he kind of laughed. Turns out he wasn’t talking about tuna fish. I said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me.’ He said, ‘I have sex all the time with the people here.’ I said, ‘I should tell you, I’m here writing a book.’ He said, ‘I’ll tell you everything!’ I warned him, ‘OK — but I’m going to use names.’ And I did.”

The book, a 1975 paperback called The Glamour Spas, sold “14 copies, all of them bought by my mother,” she says. But the publisher, Lyle Stuart, dubbed in a 1969 New York Times profile as the “bad boy of publishing,” was impressed enough with Kelley’s writing that he hired her in 1976 to write a biography of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

The crown jewel of the book that would become Jackie Oh! was Kelley’s interview with Sen. George Smathers, a Florida Democrat and John F. Kennedy’s confidant. (After they entered Congress the same year and quickly became close friends, Kennedy asked Smathers to deliver two significant speeches: at his 1953 wedding and his 1960 DNC nomination.)

“It was quite explosive,” Kelley recalls of her three-hour dinner with Smathers. “He was very charming, very Southern and funny. And he said, ‘Oh, Jack, he just loved women.’ And he went on talking, and he said, ‘He’d get on top of them, just like a rooster with a hen.’ I said, ‘Senator, I’m sorry, but how would you know that unless you were in the room?’ He said, ‘Well, of course I was in the room. Jack loved doing it in front of people.’

“The senator, to his everlasting credit, did not deny it,” Kelley continues. “A reporter asked him, ‘Did you really say those things?’ And the senator replied, ‘Yeah, I did. I think I was just run over by a dumb-looking blonde.’ “

She followed that one, which landed on the New York Times best-seller list, with 1981’s Elizabeth Taylor: The Last Star, which underwhelmed. Her next two, however — His Way and Nancy Reagan: The Unauthorized Biography (for which she earned a $3.5 million advance, $9 million in 2022 adjusted for inflation) — were best-sellers, moving more than 1 million copies each in hardcover.

She followed that one, which landed on the New York Times best-seller list, with 1981’s Elizabeth Taylor: The Last Star, which underwhelmed. Her next two, however — His Way and Nancy Reagan: The Unauthorized Biography (for which she earned a $3.5 million advance, $9 million in 2022 adjusted for inflation) — were best-sellers, moving more than 1 million copies each in hardcover.

Her 1997 royal family exposé, The Royals — which presaged The Crown, the Lady Di renaissance and Megxit mania by several decades — contained allegations that the British royal family had obfuscated their German ancestry.

“Sinatra was huge and Nancy was huge, but The Royals gave me more foreign sales than I’ve ever had on any book,” Kelley beams, adding that the recent headlines about Prince Andrew settling with a woman who accused him of raping her as a teenager at Jeffrey Epstein’s compound “really shows the rotten underbelly of the monarchy, in that someone would be so indulged, really ruined as a person, without much purpose in life.”

“Looking around,” I ask Kelley, “is society in decline?”

“What a question,” she replies. “Let’s say it’s being stressed on all sides. I think it’s become hard to find people that we can look up to — those you can turn to to find your better self. We used to do that with movie stars. People do it with monarchy. Unfortunately, there are people like Kitty Kelley around who will take us behind the curtain.”

Contrary to her public persona, Kelley is known in D.C. social circles for her gentility. Judge Kiesel, a part-time author, first met her eight years ago when Kelley hosted a reception for members of the Biographers International Organization at her home.

“What amazed me was she was such the epitome of Southern hospitality, even though she isn’t from the South,” says Kiesel. “I remember her standing on the front porch of her beautiful home in Georgetown and personally greeting every member of this group who had showed up. There had to be close to 200 of us.”

Kelley hosts regular dinner parties of six to 10 people. “She likes to mix people from publishing, politics and the law,” says Kiesel. When Kiesel, who lives in New York City, needed to spend more time in D.C. caring for a sister diagnosed with cancer, Kelley insisted she stay at her home. “She threw a little dinner party in my honor,” Kiesel recalls. “I said, ‘Kitty — why are you doing this?’ She said, ‘You’re going to have a really rough couple of months and I wanted to show you that I’m going to be there for you.’ People look at her as this tough-as-nails, no-holds-barred writer — but she’s a very kind, sweet, generous woman.”

For Kelley, life has grown pretty quiet the past few years: “It’s such a solitary life as a writer. The pandemic has turned life into a monastery.” Asked whether she dates, she lets out a high-pitched chortle. “Yes,” she says. “When asked. No one serious right now. Hope springs eternal!”

I ask her if there is anything she’s written she wishes she could take back. “Do I stand by everything I wrote? Yes. I do. Because I’ve been lawyered to the gills. I’ve had to produce tapes, letters, photographs,” she says, then adds, “But I do regret it if it really brought pain.”

Says Rubin: “People think she’s a bottom-feeder kind of writer, and that’s totally wrong. She’s a scrupulous journalist who writes no-holds-barred books. They’re brilliantly reported.”

Before I bid her adieu, I can’t resist throwing out one more potential subject for a future Kelley page-turner.

“What about Jeff Bezos?” I say.

She pauses to consider, and you can practically hear the gears revving up again.

“I think he’s quite admirable,” she says. “First of all, he saved The Washington Post. God love him for that. And he took on someone who threatened to blackmail him. He stood up to it. I think there’s much to admire and respect in Jeff Bezos. He sounds like he comes from the most supportive parents in the world. You don’t always find that with people who are so successful.”

“So,” I say. “You think you have another one in you?”

“I hope so,” Kelley says. “I know you’re going to end this article by saying … ‘Look out!’ “

This story first appeared in the March 2 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine.

https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/lifestyle/arts/kitty-kelley-interview-unauthorized-biographies-1235101933/

Photo credits: top of page, Amy Lombard; Kitty Kelley in Merc, Amy Lombard; Kitty Kelly with His Way, Bettmann/Getty Images; Kitty Kelley with Elizabeth Taylor: The Last Star, Harry Hamburg/NY Daily News Archive/Getty Images

BIO Podcast

Kitty Kelley spoke with BIO member John A. Farrell in February 2020 in Washington, D.C.

Kitty Kelley spoke with BIO member John A. Farrell in February 2020 in Washington, D.C.

Part I (26:53):

Part II (26:26):

John A. Farrell’s website: http://www.jafarrell.com/

Biographers International Organization: https://biographersinternational.org/

BIO Podcasts: https://biographersinternational.org/podcasts/

Part I URL:

https://biographersinternational.org/news/podcast/podcast-episode-45-kitty-kelley-part-i/?fbclid=IwAR0N2CMGj5Fzg5bY4Rx1VsXkGCd2HHri1K0jOKHbgf8x4uJlIwGliZWGlFI

Part II URL:

https://biographersinternational.org/news/podcast/podcast-episode-46-kitty-kelley-part-ii/?fbclid=IwAR1xJI97oOu5YbQSP2_4M6dl1DABV7g12Wnzcjp2MpdbU4fr5tHY3683kOg

BIO Board of Directors

- Linda Leavell, President (2019-2021)

- Sarah S. Kilborne, Vice President (2020-2022)

- Marc Leepson, Treasurer (2019-2021)

- Billy Tooma, Secretary (2020-2022)

- Kai Bird (2019-2021)

- Deirdre David (2019-2021)

- Natalie Dykstra (2020-2022)

- Carla Kaplan (2020-2022)

- Kitty Kelley (2019-2021)

- Heath Lee (2019-2021)

- Steve Paul (2020-2022)

- Anne Boyd Rioux (2019-2021)

- Marlene Trestman (2019-2021)

- Eric K. Washington (2020-2022)

- Sonja Williams (2019-2021)

The Lost Diary of M

by Kitty Kelley

Many intriguing stories spring from the “what if” crevices of a writer’s imagination to conjoin fact and fiction, which is how Paul Wolfe came to write his second novel, The Lost Diary of M.

Many intriguing stories spring from the “what if” crevices of a writer’s imagination to conjoin fact and fiction, which is how Paul Wolfe came to write his second novel, The Lost Diary of M.

“M” refers to the ex-wife of CIA operative Cord Meyer, Mary Pinchot Meyer, the artist who had an affair with John F. Kennedy in the White House. Months after the president’s assassination, Mary was mysteriously murdered in broad daylight while walking along the C&O Canal in Georgetown. The accused assailant was found not guilty.

“The lost diary” refers to the journal Mary kept, which was found after her death by her sister, Tony Bradlee, then married to Ben Bradlee, later executive editor of the Washington Post. Tony turned her sister’s journal over to their friend James Jesus Angleton, CIA chief of counterintelligence. The diary was never seen again, nor its contents ever revealed.

Given those established facts and a cast of real characters, Wolfe takes off in the voice of Mary, who, according to public record, was an LSD disciple of Timothy Leary who shared drugs with JFK. Enter here the fictional fantasies of “what if.”

What if Mary’s diary was not destroyed? What if it reveals her life as an ex-CIA wife? “I learned the secrets of codes and agents and networks and interrogations.” What if her diary contains all that JFK confided about the Bay of Pigs fiasco and the Cuban Missile Crisis? What if she discovers the CIA plot to assassinate Kennedy — she refers to the Warren Commission and its finding of one lone gunman as “Fictions from an Assassination.”

What if Mary storms a society ball in Washington and boldly confronts her former husband with evidence of his agency’s perfidy? What if that revelation eventually leads to her killing? What if her diary reveals her preposterous plan for world peace by having her circle of Georgetown wives give their powerful husbands LSD to lead them to “cellular evolution,” which moves them to see the folly of their power-seeking ways, and — voila! — they end the Cold War?

(I use the word “preposterous” for this fictional fantasy which Wolfe labels “Chantilly Lace,” but it’s probably no less harebrained than the actual CIA plan to assassinate Fidel Castro with an exploding cigar and, failing that, poison pills hidden in a cold cream jar.)

The challenge in writing a novel based on real people and events is making the nonfiction details so accurate that readers will accept the creative leaps. For the most part, Wolfe succeeds. One glaring exception, however, occurs when he has JFK saying to Mary that “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” That iconic phrase belonged to Martin Luther King Jr. Its placement in the novel is particularly jarring when Mary tells readers: “Then he asks me to bend toward justice and nudges the back of my neck.”

Wolfe weaves his facts and fictions so tightly, you might need Google to see if John Foster Dulles, Eisenhower’s secretary of state, and his brother, CIA director Allen Dulles, really did have “intimate business dealings with Hitler’s pals.” (They did.)

Did the British spy Kim Philby defect to the Soviet Union because he had a German mistress there, whom he later married? (He did.) Was there really an Operation Midnight Climax run by the CIA that financed bordellos and sent drug-addicted prostitutes to pick up men late at night, bring them back, and ply them with LSD-laced drinks so that agents watching behind a hidden screen could monitor the drug’s effects? (There was — and they did.)

Having hoovered the JFK oeuvre, which, according to Wikipedia, now numbers 1,000-2,000 books, Wolfe illuminates his characters with telling details: Kennedy’s “back brace,” Mary’s “unshaven arm pits.” He nails the columnist Joseph (“Joe”) Wright Alsop V as an effete snob who refuses to dine in a Paris restaurant if the wine cellar is too close to the Metro. Alsop maintains the vibrations of the train will disturb the sediment in the bottles.

Wolfe writes with grace, and many of his sentences sparkle: “The words of Ted Sorenson, the devout Unitarian, the megaphone of Jack’s mind, a poet of politics.”

So much of The Lost Diary of M will ring true to those who’ve followed the comet of Camelot, or who lived in Washington during the days when J. Edgar Hoover ran the FBI and sent his agents to hire out as waiters and bartenders to listen for gossip. One hostess confides: “The best pastry chef I ever employed turned out to be an FBI agent.” Seems comical in the age of A.I., when Alexa outperforms Mata Hari, but that was the 60s.

Kennedy aficionados and conspiracy theorists will enjoy a thumping good read and appreciate Paul Wolfe’s prodigious research, while journalists may note with interest his mention of Ben Bradlee in the author’s note, and how he questions Bradlee’s “tortuous half-century of conflicting and contradictory narratives about his ex-sister-in-law, Mary Pinchot Meyer, and his denials of his own CIA affiliations.”

What if…this is a clue to Wolfe’s next novel?

What if…Wolfe writes about a revered newspaper editor with agency connections who is driven to…

What if?

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

The American Story

by Kitty Kelley

For those who love history and enjoy biography, David M. Rubenstein has delivered a masterstroke with The American Story, in which he presents his interviews with authors of notable biographies. Among them are David McCullough on John Adams; Ron Chernow on Alexander Hamilton; Taylor Branch on Martin Luther King Jr.; Walter Isaacson on Benjamin Franklin; Robert Caro on Lyndon Johnson; and Doris Kearns Goodwin on Abraham Lincoln.

For those who love history and enjoy biography, David M. Rubenstein has delivered a masterstroke with The American Story, in which he presents his interviews with authors of notable biographies. Among them are David McCullough on John Adams; Ron Chernow on Alexander Hamilton; Taylor Branch on Martin Luther King Jr.; Walter Isaacson on Benjamin Franklin; Robert Caro on Lyndon Johnson; and Doris Kearns Goodwin on Abraham Lincoln.

In total, The American Story is a delectable smorgasbord of U.S. history, covering 39 books discussed by 15 authors, some of whom have written more than one biography.

The American Story grew from an idea Rubenstein proposed in 2013 to present a dinner series for members of Congress entitled “Congressional Dialogues,” in which he would interview acclaimed historians in the gilded setting of the Library of Congress.

He said his purpose was to educate public servants, “to provide the members with more information about the great leaders and events in our country’s past, with the hope that, in exercising their various responsibilities, our senators and representatives would be more knowledgeable about history and what it can teach us about future challenges.”

He also hoped that bringing the members together in a nonpartisan setting might reduce the rancor in Washington. Six years later, he admits the jury is out on the former and that absolutely no traction has been gained on the latter.

Rubenstein, who made his fortune ($3.6 billion) in private equity as co-founder of the Carlyle Group, styles himself as a “patriotic philanthropist,” having purchased the last privately owned original Magna Carta for $21.3 million and then loaning it to the National Archives.

In addition, he has given $7.5 million to repair the Washington Monument; $13.5 million to the National Archives for a new gallery; $20 million to the Thomas Jefferson Foundation; and $10 million to Montpelier to renovate James Madison’s home. So, when the “patriotic philanthropist” asked to host his own interviews at the Library of Congress, the answer was, quite sensibly, yes.

Yet Rubenstein brings more than his b-for-boy-billions to this book. He has delved deeply into American history, having read at least one biography of each president and “every single biography” about John F. Kennedy, the commander-in-chief with whom he feels the greatest connection.

He has donated millions to the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston, the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard, and the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, DC, where he serves as chairman of the board of trustees. He recently contributed $50 million for the Kennedy Center’s REACH expansion, upon which his name is chiseled in marble.

As much as Rubenstein admires our 35th president, however, his interview with biographer Richard Reeves (President Kennedy: Profile of Power) shows some of the dark side of JFK’s reign, including the assassination of Rafael Trujillo, the dictator of the Dominican Republic, and the attempted assassination of Fidel Castro.

Some readers will be startled to learn that JFK knew in advance about the Berlin Wall (“for which he was practically a co-contractor,” says Reeves) and had, in effect, consented to building it to protect the small U.S. force of 15,000 soldiers in West Germany from the hundreds of thousands of Russian soldiers on the eastern side.

The American Story shows almost every president to have had a flaw that scarred his legacy: FDR turned away Jewish refugees, sending them back to sure death under Hitler; JFK misfired on the Bay of Pigs; Richard Nixon resigned over Watergate; Vietnam doomed Lyndon Johnson; and, with the exception of John Adams, all the Founding Fathers owned slaves. Yet, as Walter Isaacson put it so well, “The Founders were the best team ever fielded.”

In mining nuggets of history, Jean Edward Smith (Eisenhower in War and Peace) reveals that D-Day might have failed had Hitler not been sleeping. His best Panzer tank troops were available to repel the invading Allies, but only he could give the order to use them, and no one dared wake the Führer during the initial hours of the landing. By the time he woke up, the Normandy beachheads had been secured.

Did the Allies know Hitler had orders not to be disturbed while sleeping? Or was it a matter of the great good luck that Smith said accompanied Eisenhower throughout his life?

Early in his career, Ike was almost court-martialed for claiming his son on his housing allowance for $250 (valued at $3,000 in 2017) even though his son was not living with him. Gen. John J. Pershing got the charge reduced to a letter of reprimand, and Eisenhower soared to a glorious career as a five-star general.

The Q&A format of this book is ingenious. Rubenstein, who’s mastered his subject matter, asks informed questions that stimulate impressive responses, and the “patriotic philanthropist” is not above probing into the personal and provocative:

About Benjamin Franklin: “He seemed to have a lot of girl friends.”

About Alexander Hamilton: “He had a bit of an amorous reputation. In fact, what did Martha Washington call her tomcat?”

About Dwight Eisenhower: “He was the only [WWII] general who may have had [an affair with] his ‘driver.’ Is that right?”

About Ronald Reagan: “Did he dye his hair?”

Rubenstein’s most engaging interview, with U.S. Supreme Court chief justice John G. Roberts Jr., comes at the end of the book. Roberts studied history as an undergrad at Harvard with hopes to make it his career, but then changed his mind.

“I was driving back to school from Logan Airport in Boston one day and I talked to the cabdriver. I said, ‘I’m a history major at Harvard.’ And he said, ‘I was a history major at Harvard…’ [After that] I thought I would move to law.”

Rubenstein, also a lawyer, responds: “In the first year of law school — really in the first month or two — you realize certain people have the ability to quickly do legal reasoning. They have the knack of it, and some people don’t. You must have realized that it wasn’t as hard as you had thought it would be.”

Smart as Rubenstein is, you have to love Roberts, who graduated cum laude from Harvard Law School: “It was as hard as I thought it would be. It was pretty hard throughout.”

The American Story is a creative concept that delivers delicious bite-size bits of American history to those who haven’t had the time or inclination to read widely. I devoured every page with immense pleasure.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books

Eunice: The Kennedy Who Changed the World

by Kitty Kelley

Eunice Kennedy Shriver longed to be Daddy’s little girl. “You are advising everyone else in that house on their careers, so why not me?” she wrote to her father. Joseph P. Kennedy did not ignore his daughter, but he directed his fiercest attention to his sons, determined to invest his millions in making one of them the first Irish Catholic president of the U.S. He accomplished his life goal in 1961 with the inauguration of John F. Kennedy.

Eunice Kennedy Shriver longed to be Daddy’s little girl. “You are advising everyone else in that house on their careers, so why not me?” she wrote to her father. Joseph P. Kennedy did not ignore his daughter, but he directed his fiercest attention to his sons, determined to invest his millions in making one of them the first Irish Catholic president of the U.S. He accomplished his life goal in 1961 with the inauguration of John F. Kennedy.

Still, “puny Eunie,” as her brothers called their gawky, skinny, sickly, big-toothed sister, refused to be ignored, and with determination and persistence, she finally forced her father’s admiration: “If that girl had been born with balls, she would have been a hell of a politician.”

Some might dispute any such lack as Eunice Kennedy Shriver barged into a man’s world and grabbed her rightful place alongside them, although she sometimes — but not always — considered them to be her betters.

She founded the Special Olympics, which spread to 50 countries, and because of her, those with physical and intellectual disabilities are no longer locked away. Society now educates them, employs them, and helps them thrive.

Eunice used her father’s vast connections and immense fortune to her best advantage. (She got admitted to Stanford because Joe Kennedy asked his friend Herbert Hoover to make it possible.) Through her father, she landed a job in the Justice Department as a special assistant to U.S. Attorney General Tom C. Clark. “Joe Kennedy had secured Eunice’s job the same way he had engineered a U.S. House seat for Jack,” McNamara writes, “with good connections and cold cash.”

During that time, Eunice and her brother Jack lived together in Georgetown, where they had an Irish cook and numerous friends, including Senator Joseph McCarthy and Congressman Richard M. Nixon of California. In her unpaid position, she developed interest and expertise in juvenile delinquency and appealed to her father for help in setting up a scholarship program.

Joe responded that the Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr. Foundation, established to honor his firstborn, killed in WWII, “would be glad to defray any expenses…in Boston.” Perceptively, McNamara notes “the random nature and mixed motives of the Kennedy Foundation’s early philanthropy. Solving social problems did not preclude advancing his children’s careers.”

Within a few years, Eunice commandeered the foundation and directed its resources into the field of mental retardation, perhaps in expiation for the plight of her sister Rosemary, the family’s special-needs child.

Recognizing Rosemary’s severe disabilities in London, when he was serving as U.S. ambassador, Joe Kennedy decided his daughter should undergo the experimental psychosurgery of a prefrontal lobotomy, which went horribly wrong, rendering Rosemary unable to function on her own.

Afraid that the stigma of mental retardation might affect the political ambitions he had for his sons, Kennedy sent Rosemary to be cared for by the Sisters of St. Francis of Assisi at St. Coletta School for Exceptional Children in Jefferson, Wisconsin. Her absence was not mentioned by her parents or her siblings for 30 years, until Eunice began “reintegrating her sister into the family that abandoned her.”

Like her mother, Eunice Kennedy Shriver was a zealous Catholic who accepted all the tenets of her church, including the sanctity of marriage and the abomination of abortion. Yet she turned a blind eye to the marital infidelities of her father and her brothers.

In 1980, when Gloria Swanson published an autobiography and revealed her long affair with Joe Kennedy, who took the Hollywood actress on family vacations with his wife and children, Eunice took umbrage. She fired off a blistering letter to the editor of the Washington Post, which McNamara does not mention. Extolling her mother as “a saint” and her father as “a great man,” Shriver lambasted Swanson’s revelation as “warmed-over, 50 year old gossip that accuses the dead [my father] and insults the living [my mother]…The closeness [my father] shared with my mother and her obvious devotion to him inspired his children to revere the values of home and family as well as public service and dedication to others.”

By that time, the sexual romping of the Kennedy men — father and sons — had become proven fact. The only marriage of Rose and Joe Kennedy’s nine children which still seemed intact was that of their fifth child, who adored the Blessed Virgin Mary and wanted to become a nun before she was persuaded, after a seven-year courtship, to marry R. Sargent Shriver.

That 1953 wedding was as grand as a coronation, with Francis Cardinal Spellman celebrating the nuptial Mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, assisted by three bishops, four monsignors, and nine priests. The 32-year-old bride wore a white Christian Dior gown made in Paris, and 1,700 guests danced to a 15-piece orchestra on the Starlight Roof of the Waldorf Astoria.

But the wedding might not have occurred without the intervention of Theodore Hesburgh, the charismatic young priest from the University of Notre Dame who was prevailed upon by Joe Kennedy to persuade Eunice not to enter the convent, which Joe felt would be detrimental to JFK’s political career.

Because of Father Hesburgh’s high esteem for Sargent Shriver, he agreed to be Joe Kennedy’s heat-seeking missile, summoning Eunice for “a frank and honest exchange.” He told her that her vocation was not the convent but to marry Shriver, have his children, and continue the work she was doing with the mentally challenged.

He later told McNamara that Sarge “was the best, the very best of the bunch. I knew her not as well as I knew him, but she was a great gal. There are a lot of Kennedys. They come in all shapes and sizes. But who did the work she did? Who cared for Rosemary as she did? It took a lot of strength, I will tell you that. The men tend to outrank the women in that family, but she had as much or more to offer as any of them.”

Eileen McNamara writes with grace, elegance, and diplomacy, never making moral judgments on harsh facts. If she were not doing laudable work as chair of the journalism program at Brandeis University, the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer would make an excellent secretary of state. Her fine biography of Eunice Kennedy Shriver champions the overlooked sister, who deserves as much, if not more, applause than her celebrated brothers in establishing the family’s monumental legacy.

Crossposted with Washington Independent Review of Books